Crux fidelis, inter omnes arbor una nobilis;

nulla talem silva profert, flore, fronde, germine,

dulce lignum, dulci clavo, dulce pondus sustinens!

Flecte ramos, arbor alta, tensa laxa viscera,

et rigor lentescat ille, quem dedit nativitas,

ut superni membra regis, miti tendas stipite.

Sola digna tu fuisti, ferre saeculi pretium,

atque portum praeparare, nauta mundo naufrago,

quem sacer cruor perunxit,, fusus agni corpore.

Amen

O faithful cross! The one noble tree, among all trees;

no forest yields your like, in foliage, flower and fruit;

sweet is the wood bearing, a sweet burden with a sweet nail

Bend your limbs, O lofty tree, relax your tense fibres,

and let that hardness, which your nature gave you, soften;

that you may stretch on a tender trunk, the members of the heavenly king.

Thou alone wast worthy, to bear the price of the ages,

and, as a seaman [nauta], to ready the port for the shipwrecked world,

whom the Precious Blood anointed, shed forth from the flesh of the Lamb.[1]

Amen.

(Venantius Fortunatus (ca. 530 – ca. 610))

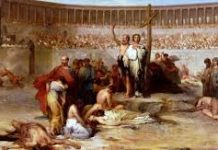

The image of the cross as a tree is beautifully expressed in the first of these closing verses. There is a long history behind this image, which we find implied at the start of the poem where the cross is referred to as a trophy: “the noble triumph of the trophy of the cross.” That word, “trophy” is particularly appropriate here, for the Latin word, tropæum, referred originally to “the trunk of a tree on which were fixed the arms, shields, helmets, etc., taken from the enemy”[2] Later it became a stone monument, but here we have a most satisfying return to the original meaning, for surely for us the wood of the cross remains the trophy of Christ’s victory over Satan. The comparison of the cross to a tree is continued in verse three, which portrays God as marking for future use the tree in the Garden of Eden where Adam and Eve sinned.

Venantius Fortunatus is here referring to a legend by which the cross was made from the wood of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.hese three verses conclude a much longer hymn, the full text of which can be found at the end of this article. You may have noted that it was written by Venantius Fortunatus, who was also the author of Vexilla Regis, a hymn discussed on Palm Sunday. And, if you were to examine the full version, you would find that its first line—Pange, lingua, gloriosi—was quoted by Saint Thomas Aquinas at the opening of his Eucharist hymn (Holy Thursday).

The exuberant tenderness of these verses is a powerful summons to compassion for the crucified Christ. The poem personifies the cross, inviting it to soften its natural hardness as a parallel to a softening of our hardened hearts as we seek the port of salvation into which, in a complicated metaphor, the blood of Christ sweeps us like a wave in the sea carrying survivors of a shipwreck to safety.

When Adam died, Seth obtained from the guardian cherubim of Paradise a branch of the tree from which Eve ate the forbidden fruit. This he planed on Golgotha, called the place of the skull because Adam was buried there.[3] From this tree, as the ages rolled one, were made the ark [of the covenant], the pole on which the brazen serpent was lifted up,[4] and other instruments; and from its wood, by then grown old and hard, at length was made the cross.[5]

There is a reminiscence here of Psalm 17/18:

With the Loyal thou [God] dost show thyself loyal;

with the blameless man thou dost show thyself blameless;

with the pure thou dost show thyself pure;

and with the crooked thou dost show thyself perverse.

The point is that Satan may have exhibited cunning when he tempted Adam and Eve at the tree, but God was more cunning in that he singled out that very tree to provide the wood of the cross: “the Creator then marked the tree that would undo the harm wrought by a tree.” We find here a theme that appears in may guises: the instrument of man’s fall became the instrument of redemption. One would be Saint Paul’s identifying Christ as the new Adam. Aa variation is found in the identification of Mary as the new Eve; the obedience of one cancelled the disobedience of the other.

The career of Jesus is briefly described, beginning in creation and continuing until “when the time had fully come, he was born of a woman,”[6] destined to be the true paschal lamb “lifted up on the tree of the cross.” Verse six is a poetic tour de force, in that Venantius parallels the instruments of the passion with cosmos itself: “the vinegar, the gall, the rod, spit, nails and the lance” correspond to “the earth, the sea, the stars,” all of which are bathed in the redeeming water and blood that flowed from the side of Christ. I wonder if Shakespeare, when he wrote Macbeth, was not drawing upon the imagery of this hymn, which he could well have known from his youth.[7] In the play the gentle and munificent King Duncan is murdered by his own people, suggestive of the passion of Christ. And his blood, like Christ’s is abundant: “who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him.”[8] Macbeth refers to Duncan’s innocent blood in terms that echo Venantius’s hymn: “Will all great Neptune’s ocean wash this blood clean from my hand? No, this my hand will rather the multitudinous seas incarnadine, making the green one red.”[9] Who can read this without being reminded of the blood flowing from the open side of Christ: “Water flows forth and blood, in which flood the earth, the sea, the stars, and the whole word is bathed”?

These ancient hymns, hallowed by centuries of use in the Church, remain meaningful for us today. Our observance of Holy Week, curtailed this year because of the COVID-19 virus, would be enhanced by our reading and rereading them as we meditate on the sacrifice Jesus made to renew mankind, a sacrifice that we shall encounter sacramentally when once again we gather around the altar for the celebration of Mass.

Pange, lingua, gloriosi, proelium certaminis,

et super crucis tropæo, dic triumphum nobilem,

qualiter redemptor orbis, immolatus vicerit.

De parentis protoplasti, fraude factor condolens,

quando pomi noxialis, morte moru corruit,

ipse lignum tunc notavit, damna ligni ut solveret.

Hoc opus nostrae salutis, ordo depoposcerat,

multiformis perditoris, ars ut artem falleret,

et medelam ferret inde, hostis unde laeserat.

Quando venit ergo sacri, plenitudo temporis,

missus est ab arce Patris, natus, orbis conditor,

atque ventre virginali, carne factus prodiit.

Lustra sex qui iam peracta, tempus implens corporis,

se volente natus ad hoc,, passioni deditus,

agnus in crucis levatur, immolandus stipite.

En acetum, fel, arundo,, sputa, clavi, lancea:

mite corpus perforator,, sanguis, unda profulit

terra, pontus, astra, mundus,

quo lavantur flumine!

Tell, tongue, the battle of that glorious, combat, and speak forth the noble triumph of the trophy of the cross,

how the redeemer of the world, having been immolated, will have conquered.

Grieved by the infidelity of our first-created parent, when with a bite of the fatal fruit he fell into death,

the Creator then marked the tree that would undo the harm wrought by a tree.

This work of our salvation had demanded that cunning

would outwit the cunning of the multiform deceiver,

and thence would bring the remedy whence the foe had wrought the injury.

When, therefore, the fullness of the sacred time was come,

[the Son], the creator of the world, was sent forth from his Father’s home,

and, clothed in flesh, he came forth from a virginal womb.

Thirty years now completed, the period of his earthly sojourning,

of his own free will, born for this he gave himself up to his passion,

and, as a lamb to be slaughtered, he was lifted up on the tree of the cross.

Behold the vinegar, the gall, the rod, spit, nails and the lance; his tender

body is pierced. Water flows forth and blood, in which flood

the earth, the sea, the stars, and the whole word is bathed.

[1] This verse was translated by David Foley

[2] C. Lewis and C. Short, A Latin Dictionary, (1879), s.v. tropæum.

[3] Some crucifixes honour this tradition by showing Adam’s skull and crossbones attached to the base of the cross.

[4] Num 21.8.

[5] Elizabeth Rundle Charles, The Christian Life in Song, (London: Nelson, 1888).

[6] Gal 4.4

[7] All the more so, if he was a Catholic as Clare Asquith argues in Shadowplay: The Hidden Beliefs and Coded Politics of William Shakespeare (London: Public Affairs, 2005).

[8] Lady Macbeth, in act V, scene 1.

[9] Act II, scene 2.