(We thought we would publish a bit of fiction in these pages, for light, yet edifying and educational, relief from the barrage. Here is contributor Carl Sundell’s story, with, as he puts its, a theme is rooted in Pascal’s Wager argument, and reference to an historic debate between Chesterton and Darrow. Chesterton won the debate according to a vote taken with the audience of 3,000, at least according to a New York Times review)

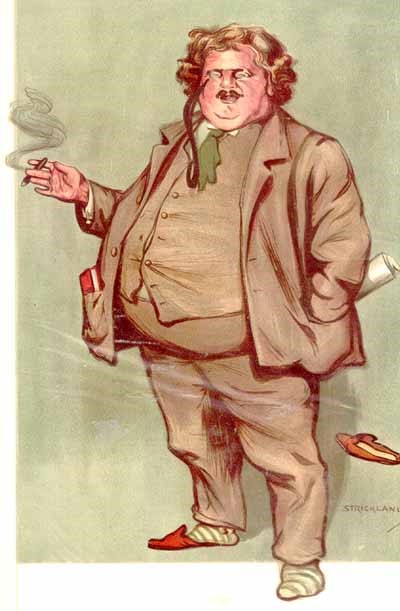

Gilbert Keith Chesterton, touted by friends and critics as arguably the “biggest” literary giant of the twentieth century, was satisfied that he had done his good deed on this sweltering August day in 1931. No one around was gargantuan enough (321 pounds) to offer his subway seat to three panting and perspiring old ladies. The now aging literary lion tightly gripped the ceiling strap of the underground bullet as it hurtled him swaying to and fro from station to station beneath the great metropolis. At last, the screeching stop he had been waiting for … Times Square. He glanced at his pocket watch … in four hours, the great debate.

Unwilling to trust the moving escalator stairs (perhaps they would collapse under his great bulk and he would sink bellowing at the top of his lungs into the bowels of the machinery below) the poet heaved his huge bulk slowly up the seemingly endless stairwell, pausing to catch his breath at two landings, until he arrived finally at street level and hailed a cab. He counted on the driver to recommend a first rate restaurant where he would dine and relax before his evening debate with the legendary atheist lawyer, Clarence Darrow. The subject of their debate for several days had been well advertised in a headline of the New York Times: “Does Religion Have a Future?” Three thousand tickets had been sold for the event to be held at the Mecca Temple. It did not occur to Chesterton that he should worry about the outcome. After all, hadn’t he performed on the platforms of England with the likes of Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells, and Bertrand Russell? Still, Darrow was known for clever tricks of logic, as the fiery orator William Jennings Bryan had learned to his dismay at the Scopes “Monkey” Trial. The poet would have to tread carefully this night, he mused, lunging into the back seat of the cab.

“Take me to New York’s best Italian restaurant,” said the great man. “I trust your opinion.”

“Yes, sir. That would be Carlo’s, from what my fares tell me. Never ate there myself.” The cabbie saw his huge fare lean back and close his eyes.

But soon Chesterton glanced downward and noticed that the well-worn rubber tip of his cane had fallen off, probably while he climbed the subway stairs. He would have to get another before going to dine.

“First drop me at the nearest convenience store, driver. I need to get a rubber tip for my cane.”

“Right you are. I can tell by your accent you’re British. There’s a place just around the corner.” The cabbie seemed pleasant enough, unlike others the poet had encountered. He closed his eyes again and started to nod. “Here we are, sir. I’ll wait for you” the driver interrupted.

“Yes, I’ll be just a moment.”

This was not a savory neighborhood, the poet observed. Inside the store he sauntered over to the candy rack and swiftly seized a half dozen of the American candies he had come to like … Hershey with Almonds and Snickers best of all. As he was about to approach the sales clerk and ask the location of cane tips, an old, rather desperate and unkempt man tugged at his coat sleeve.

“I’m Shannon Coffey, sir. Please come with me!”

Shannon Coffey was too good a name for this sad looking wretch, the poet decided. He would have to keep the name in mind as a moniker for the hero in his next round of detective stories. The old man’s soiled hands tugged again at his sleeve. There was something vaguely unsettling about him. His face did not register natural, as if it had been cosmetically or surgically altered for some sinister purpose. Behind his outward features there seemed to lurk a once handsome, intelligent, and prosperous gentleman. Yet another urgent tug at his coat sleeve.

“Why should I go with you?” Chesterton calmly inquired.

“You are bidden to a challenge by the greatest brain of the century,” Coffey blurted.

“Yes, well I suppose Mr. Clarence Darrow is brilliant, at least by his own estimate.”

“Not him. Not that fool,” Coffees napped. “Come, I will introduce you to the Master Mind of our age.”

“Indeed, who would that be?”

“You’ll find out in person … won’t you?” The old man grinned through teeth blackened by abuse and neglect. “Come now, my fat friend, follow me for the treat of your life, hee-hee!” With that he whirled about and sped out the back door into the alley.

This was definitely too good an offer to refuse. After many years the poet still carried the pistol he had bought to defend his wife on their honeymoon. Also, very possibly the sharpest sword in Europe was concealed inside the length of his cane. Now this so-called “master mind of our age” might well turn out to be a great warm-up exercise for the debate with Darrow. Throwing caution to the wind, the poet lumbered out the door behind Shannon Coffey into the dark alley waiting to engulf them both.

And engulf the poet it certainly did. When he awoke he did not know how long he had been unconscious. The painful throb in his head made him wish he had not woken. He was lying on his back on something very flat and hard. He could tell from the silence and the still air that he was inside … but inside what? And where? He reached in his coat pocket for a match. The pocket was empty. He reached for his pistol … gone, of course.

He was in very deep trouble. There were two options: stay quiet, wait, and consider a strategy; or stir and let his captors know he was ready to confront them … for what ungodly purpose he did not know. Then he heard the sound of an old Victrola machine in the distance, something wildly discordant … Stravinsky, no doubt. Now a human voice roared maniacally loud and determined to match the fevered pitch of the orchestra. This was not helping the throb in Chesterton’s head.

Since the room was pitch black, he did not know which side of whatever he was lying on he should turn to in order to rise up and explore the room. Moreover, given his bulk, if he had to drop from a higher to a lower level, the sound of his landing might alert someone. But the music, as some might laughingly call it, would save him from discovery. Just as he was about to make his move, the music stopped. Footsteps approached. The door, flung open, banged against the wall. Now he realized he was lying on the floor. The light from the adjoining room framed the figure of Shannon Coffee standing over him.

“Allow me to introduce you to … the Master Mind of our century,” said the frail old man. He moved aside into a shadow. After a moment, a figure stepped into the now well-lighted doorway. At first Chesterton thought it was a small boy. Then, as his eyes got used the light, he realized that this was a very small man … to be exact, a midget. And a rather old one, shriveled with wrinkles, balding, and bowlegged. He had seen midgets before, little people well-proportioned in their various body parts, but this fellow was altogether out of kilter. It wasn’t just the legs and rather long arms … most of all the head that was so much larger than one would expect. Had one parent been a midget and the other a dwarf?

“I am Shannon Coffey,” the strange little creature announced with a lisp. “The man who brought you here uses my name because he cannot remember his own. I see you are trying to rise up to greet me, but you will not. My lieutenants have slugged you in the head and injected you with a drug that has paralyzed you from the waist down. I don’t mind complaining that it was like unloading the Titanic for my men to carry you from the truck to this room. When the chemical wears off, you may get up as you like. Just remember that I carry a pistol in my pocket … your little pistol in fact … loaded with your little bullets. Thank you for that gift, Mr. Chesterton. I will mount it on my library wall as a trophy. Please try not to get bullets lodged in your body as trophies of our meeting.”

“I must be dreaming,” the poet hoarsely remarked.

“Not at all,” the midget said, his voice now more high pitched and discordant, surely the voice the poet had heard singing to Stravinsky’s wild strains.

“Well then, why have you captured and drugged me? What ungodly business can we have to do with each other?”

“Very simply,” Coffey said, taking a step toward Chesterton, “a meeting of minds … or should I say an engagement of the two greatest minds of the century … yours and mine. I have, as so many others, admired your writings for many years. Admired and detested them too. Most unfortunate for you. I must tell you that I am the President of a little known secret organization called SAAC, or the Society for Advancing the Annihilation of Christianity. It is our business to know the enemy and know him well because knowledge is power. I know, for example, that your intellect towers over the likes of Clarence Darrow. I intend to save him from the humiliation of defeat in tonight’s scheduled debate with you at the Mecca Temple.”

“Why should you care how it goes one way or the other? Surely the fate of Christianity does not hang on what happens tonight at the Temple.”

“I do care how it goes for Mr. Darrow because he and I are kindred spirits. We are both atheists … I do not like to see an atheist trounced in battle by a Christian, and I do think there’s a good a chance of that if you are the contender. So I will not let you win this evening’s match. Your legs, quite simply, will not carry you to the main event. Darrow will prevail just by your failure to show up, and so you’ll be mightily disgraced. This is not to say you cannot go a few rounds with me, if you like. I have no more pressing engagement at the moment.”

“Before you say another sentence,” the poet said with a sigh, “I need to know if you plan to kill me for your amusement.”

“We will leave before the drug wears off. You will be free to go when it does,” the little man said. “You certainly miscalculate if, like so many Christians, you think that because I am an atheist I must also be a monster. And after all, there is no need to kill you. Why should I bother? You are killing yourself with food and drink. That is clear just from the looks of you.”

“Are you going to take my cane for a trophy too?” the poet asked.

“No, it is lying by your left side. You may reach for it. But don’t get your hopes up. I’ve removed the hidden sword. As you can see, I think of everything.”

“That’s why we call him the Master Mind of the century, hee-hee!” came the familiar frail voice from out of the shadows.

“Well then,” said the midget, “will you engage me with some fascinating talk … or, at this moment of momentous defeat, would you rather … take a nap?”

The poet reached for his cane and felt the smooth bronze knob handle that had always been a welcome home for his hand. This could still be a potent weapon, he thought. If he could use it to strike with all the force of his three hundred pounds … he might knock down anyone guarding the exit doors and make his escape. But his feet felt like lead weights. He could lift neither leg, and the midget had made sure he was just beyond the poet’s reach.

“What’ll it be – talk or nap?” Coffey impatiently demanded.

“He wants to sleep, I’ll bet,” came the voice from the shadows. “All bravado and bluff is this elephant man, hee-hee!”

“As you please,” the poet said, shrugging his shoulders as if already resigned and bored with the game.

“Oh, I don’t like that attitude,” the Master Mind retorted. “You must stir yourself up to an intellectual frenzy if you want to play with me.” The poet did not reply. “All right then, my move.” For a moment the midget put his finger to his lips, as if pondering his opening gambit. “Well then, Gilbert Keith Chesterton, I say there is no God …that the notion of God is a desperate one for desperate people … and that you cannot suppose God exists just because you would desperately like God to exist.”

“Nor can you say God does not exist because you might prefer He did not,” replied the poet. “Scratch an atheist and you will find a man whose Nogod is grounded in some reason buried deep in his heart. There may be any combination of a thousand reasons why the atheist flees from God. But the whole weight and flow of human history has been for God and against Nogod. Consider that handful of grain recently found inside an Egyptian tomb at least five thousand years old. It was sown recently and sprang to life. Because a thing is old, that does not mean it has no grand or eternal purpose. Religion will last as long as man because it was in us from the beginning. Why shouldn’t it be in us at the end?”

Shannon Coffey’s face was blank, as if he could not hear any of the poet’s words but was wrapped up in his own maniacal mindset. He resumed hotly with the conviction that his argument was irrefutable.

“Moreover, the old saw, ‘There are no atheists in foxholes,’ is absurd on the face of it. The foxhole is in fact the first place to look for an atheist, because in the foxhole, after a man has witnessed the horrors men can inflict upon each other, he is least likely to believe that the human soul can be a temple of the Holy Ghost … more likely the tomb of an unholy ghost.”

“A beautiful th-th-thrust,” came the voice from the shadows.

“Don’t you think for a moment,” Coffey blurted at the shadow, “that the fat man is mortally wounded just because he is flat on his back. Come now, Gilbert Keith, you must get into the spirit of verbal swordplay. I know you are superbly up to it.”

As a matter of fact, the poet’s head was still sore from the blow. He could feel quite a knob rising on the back of his skull. He was not superbly up to anything for the moment. Yet … was that a tingle he felt in his feet? No, it was a tickle. There was a slight sensation, something like small fingers were tugging to remove his shoes and socks.

“There are foxholes … and then there are foxholes,” Chesterton said.

The midget waited for the poet to resume.

“You see, you have never really been in a foxhole,” the poet insisted.

“Neither have you, I think,” Coffee insisted.

“Ah, but there you are wrong,” Chesterton protested. “When I was in my teens, I contemplated suicide. I still have a photograph of myself at that age, which, if you could see it, you would agree verifies the state of mind I was in back then.”

“So how did you dig your way out of that foxhole?” the midget asked.

“I asked myself this: if the world was meaningless, as you might say in your atheistic way, then why did I search for its meaning? I knew I was searching for something that existed or why would I so desperately be looking for it?” Now sensation was returning to his legs, but very slowly.

“Now I think you are not being rational, sir. Some men imagine they might find a pot of gold at the end of a rainbow. That doesn’t mean the gold is there,” Coffey retorted.

“But they first had a notion of what a pot of gold is. Likewise, I have a notion of meaning in my life because everywhere I look I find meaning or purpose. The purpose of a mother and father is to raise a child. The purpose of a government is to rule the people. The purpose of science is to find out how the universe works. The purpose of a poem is to calm my savage breast.”

“And so …?”

“So there you have it. The untrained instinct of my youth said that if everything has a purpose, then the whole universe must have a purpose. Why should everything in the universe have a purpose except the universe taken as a whole? And since science was in no position to define that purpose, I went to the well called religion and dipped my bucket and quenched my thirst.Religion alone, I found out, offers the ultimate answer to the despair that urges us all to run to the gallows and hang ourselves.”

“Ha!” the midget snickered. “I am an atheist and I assure you I have never been tempted to run to the gallows!”

“Well, not in this life anyway. I’m sure you’ve found your consolations, as I have found mine own … mainly in food and drink. But in the last analysis, you too are heading for a foxhole.”

“Whatever can you mean?” the Master Mind haughtily retorted.

“Surely you realize,” the poet said solemnly, “that at the hour of your death you will be in the worst possible foxhole.”

“I admit nothing of the sort. Death will be as welcome to me as life has been. Everything is natural and therefore good. I don’t mean to put on heroics, but I do not fear my demise.”

“Ah, says you. You don’t fear it at this minute, perhaps,” said Chesterton. But how do you know you will not fear it in the very last hour of your life? Can you be so sure that at moment of your death you will not reach out desperately for Life?”

“Life? Do I look like a sentimental fool to you? Now Gilbert, you need to get a grip on reality. Do you really think the old boozer standing behind me in the shadows is the apple of God’s eye? Please join me in a great laugh at the very thought. Why, this wretch cannot even remember his own name. If there were a God, he would love the strong, not the weak. He would admire his best handiwork, not his worst.”

“I see you have gone the way of Nietzsche’s Superman,” the poet commented wryly. “You and Bernard Shaw should compare notes.”

“We already have,” the midget replied. “It was I who urged him to write Man and Superman. He is obliged to me for conceiving that great second act … a fantastic piece of theater, don’t you think?”

“I’m sorry to admit that I slept through parts of it,” the poet apologized. “I will say what I have said before: Mr. Shaw is himself a wonderful work of art; if only, like the Venus of Milo, he had arms to reach out and embrace the human race instead of reaching desperately for his vapid Superman. In any case, you have not disproved my notion that you are already in a foxhole of your own making, and at some distant hour when the bomb of your own annihilation starts bursting overhead, I wonder if you will not cower and whimper along with the rest of humanity for God’s abiding mercy.”

“I truly detest your cowardly logic,” the midget sneered.

“If I could just get on my feet, you would find out what a coward I am!” The poet closed a fist and shook it at the little man. Then it happened. The Master Mind showed his true colors. He scampered around to Chesterton’s left side and snatched the cane from the poet’s reach. Now he stood near the poet’s feet and began to stroke them, each one in turn gently at first, with the brass head of the cane; then harder … and harder.

“I say,” the midget exclaimed. “You have the largest and fattest feet I have ever seen. It is really a pleasure to massage them. FEEL ANYTHING YET?” the midget shouted. “Do let me know when you feel it!”

He felt it with a sudden rush of pain at about the twelfth fierce blow.

“I FEEL IT NOW!” bellowed Chesterton. “But I don’t understand! Are you trying to knock atheism into my feet? That won’t work!”

“No,” the midget retorted. “I’m trying to knock you out of your foxhole. I want to give you the courage to face death without leaning, like all the other cripples of your breed, on some make-believe prop. You know the old saw … everybody want to go to heaven but nobody wants to die. Gilbert, wake up and smell the world. Enjoy it to the hilt. It’s all there is. Now I’m not going to kill you, but I’m hoping to make you really wish you were dead! I’m going to make you hope with the greatest zeal for the annihilation of your body and soul. NOW TAKE THIS!” With that, the Master Mind gave three great cracks to each foot with the cane’s brass handle.

“That’s enough of that!” roared a new voice from the shadows. “Drop the cane or I’ll drill you with this sword!” The man who had been hiding in darkness stepped into the light and Chesterton could tell, in spite of his own howling pain, that this was not the same man who had disappeared into the shadows. He wore the same clothes and the same unkempt beard, but the dull look in the old man’s eyes had been replaced by something like a wild and demonic light that shone through them. And he suddenly seemed six inches taller.

“Drop that cane,” the old man ordered again, “or I’ll dig the deepest foxhole you ever slept in.” Then he swung the sword and narrowly missed lopping off the midget’s head. “Oops! Poor aim, sorry … let me try again.” He reached back to give another mighty swing.

“Oh, my God, MY GOD …!” the Master Mind shrieked.

“Your WHAT?!” the poet and the swordsman shouted together.

There comes to certain men a moment in life that defines the very essence of being alive. There comes a lightening insight followed by rolling thunder in the breast, so perfect and ultimate, that the fate of the universe seems in peril if the dreaded words are not spoken … and then spoken again!

And so, in unison the poet and the swordsman repeated with a great bellow: “YOUR WHAT?!”

The midget appeared in shock, his jaws agape and eyes bursting from their sockets. He had said the words. He could not deny he had said them. He had said the damnable words … and had been tricked by an idiot underling into saying them. Then he fell, the very short distance he had to fall, to his knees and he sobbed convulsively into his hands.

“Coffey, it seems we are in the same foxhole at last,” the poet remarked. “We have both learned to pray. But to what soldier of Christ do I owe my rescue, may I ask?” he said pointedly to the warrior still brandishing his weapon.

The old man lifted the sword in a half clumsy salute to the poet. From his broad chest erupted a baritone sound more forceful and resonant than the poet remembered.

“Sir, my name is John Cone. Twenty-three years ago, in my prime, I was elected Supreme Knight of the Knights of Columbus. My tenure in office lasted but one year. I couldn’t stand the paperwork. Another Knight was found by temperament more suited to bureaucracy. I was summarily put out to pasture, as they say, but I was not content. The Supreme Council observed my talent for being a thorn in the side and called me out of retirement on special occasions for undercover work, to infiltrate and spy on any organization bent on the slander and destruction of the Roman Church. Lucky for you, as you can see. My penetration of Master Mind’s ring of thugs resulted in his orders to kidnap you, of all people … a fellow soldier of Christ. To have been of service by undoing Coffey’s plot to sabotage your debate with Darrow makes this the luckiest day of my life, perhaps yours too. I release you, sir, from your bondage to our little Master Mind here.” The midget, sitting motionless on the floor, stared comatosely into his own foxhole of empty space.

The Knight returned the sword to its sheathe inside the poet’s cane and tendered it to its owner.

“Your sword is a most worthy one, Gilbert Keith, and I offer to sponsor you should you decide to become a Knight of our Order. You must hurry and go now. I have been exposed. My secret service is over, but it will have been worth sending you into battle with Clarence Darrow. Godspeed, then!”

“What about Coffey?” Chesterton inquired, concerned as to how the Knight of Columbus might treat him.

“Don’t you worry about this one. I’ve dealt with his kind before. He’ll be making the sign of the cross three times over his next meal. For all we know, before the Holy Spirit is done with him,” Cone said, his face for the first time hinting at a satisfied grin, “he may against all odds become the tallest soul in Christendom.”

And sure enough, there was little Coffey on his knees now, shivering in his sweat, bent in a kind of humble supplication before … the Almighty? If tall was in his future, it was hard to imagine at that moment. But then, rather curiously, the little man with the big head fixed an impish grin on his face, glared at the poet, and winked. The poet caught himself inexplicably winking back.

But the Knight of Columbus scowled at the poet. “Now get on your way!” he exclaimed. “Do you want Darrow to win by default? Move it, genius! And don’t forget to eat those candy bars on the way!”

The poet awoke with a start. The cabbie had slammed his brakes and shouted at a strolling pedestrian, “Move it, genius!” Half a minute later the cab careened to a stop in front of Carlo’s Restaurant. Chesterton rubbed the sleep from his eyes and glanced at his cane, still wearing its trusty old rubber tip. Judging by the amount of the fare, he concluded the driver had caught him napping and had decided to take the longest possible route to Carlo’s. He left a large tip anyway, as the dream surely had been worth the fare.

Famished, he availed himself of the varied and spicy Italian cuisine he preferred to the British menu. For antipasti he took spinach with bacon vinaigrette, fried shallots and shaved goat cheese along with focaccia bread. For the main course he chose pan-roasted baby chicken almandine with sweet onions and braised red peppers. The meal was topped off with a slice each of creamy black-and-white cheesecake and walnut fudge pie with maple ice cream. All of this he washed down with an absurdly expensive bottle of 1925 Marques de Riscal. During an after-dinner glass of Butterscotch Schnapps, he penned a brief verse on his linen napkin:

Dining Gilbert Chesterton spilled sauce and ale his big vest on.

He carved his Kant, mashed his Marx and buttered his Bertrand Russell.

Then he shouted down the corridor for some oyster and some mussel.

But last of all, with sweating brow

he opened wide his jaw,

and for dessert he gulped a slice

of good old Bernard Shaw.

Later that evening, at the Mecca Temple, G.K. Chesterton also devoured Clarence Darrow before an enthused crowd of three thousand souls. In that, at least, Master Mind had been right to fear. According to a vote of the audience taken after the debate, the poet vanquished the lawyer by a margin of nearly one thousand ballots. The landslide victory was described without fanfare in the New York Times by a reporter seemingly oblivious to the historic moment he had been so lucky to witness.