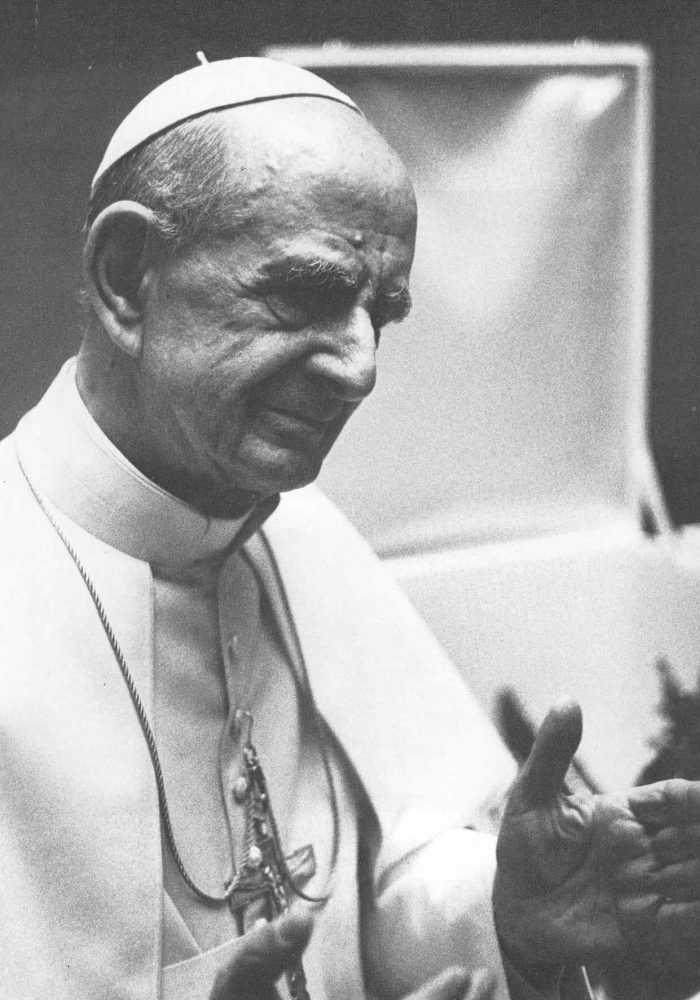

Today, May 29th, is the optional memorial of Pope Saint Paul VI, celebrated on the anniversary of his ordination in 1920. This year, ironically, this is also the universal Solemnity of the Ascension, which Paul VI’s controversial liturgical reforms allowed to be moved to the following Sunday, when it is held here in Canada. We’ve written on how this attenuates the oldest ‘novena’ in the Church, the nine days from Ascension to Pentecost.

Paul VI’s own birth name was Giovanni Battista Enrico Maria Montini, coming into the world on the 26th of September, 1897. He was of the ‘upper crust’ of Italy, descended from the minor nobility– hence, the hefty moniker – as were almost all the Popes of the past four centuries. Pius X was an exception, still Italian, but of peasant stock, as was John XXIII.

Giovanni entered the seminary at 19 years of age, destined for diplomatic service in the vast bureaucracy of the Vatican City State, and never looked back, as far as we know. Whatever controversies arose in his later life – and there were many – he seems always assured of his vocation as a priest, solid in his celibacy and life of regular, traditional piety – his few encyclicals evince as much. He wrote the first of them on God’s Holy Church (Ecclesiam Suam), in 1964, in the midst of the Council, promulgated on the feasts of the Transfiguration, coincidentally, the day he himself would die fourteen years later. The next two, both on Our Lady (Mense Maio, April 29, 1965) and Christi Matri (September 15, 1966) he wrote just after the Council. Then there was one reaffirming priestly celibacy (Sacerdotalis Caelibatus, June 24, 1967), which some bishops and priests wanted to abolish, on the feast of his namesake, John the Baptist.

His last encyclical was the landmark Humanae Vitae (1968), promulgated on the feast of Saint James, July 25th; fitting, as it was a courageous act of martyrdom, those few pages that were so contra mundum, a prophetic voice to a world drowning in its own hedonism. He wrote no encyclicals after that, even though he governed the Church for another decade. No one quite knows the reason, but perhaps the Pope by this point had become disillusioned, the backlash against his re-affirmation of the Church’s condemnation of contraception and his re-affirmation of the beauty of married love, was far more than he expected, and perhaps more than he could handle. It seems as though events happened around him, and he trusted others too much, expecting they would be like himself. Was not God guiding His Church, and would not Catholics just go along, as they had always done?

But the revolution had begun, the ‘Sixties’ opening up a floodgate of evil, rebellion, even apostasy, in the midst of the ongoing effects of which we are still living, half a century on.

More mysterious is his reform of the Liturgy, not just the Holy Mass, but of all the other sacraments, as well as the Divine Office, according to the prescriptions of the Council’s Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilum. The wide scope he gave to Archbishop Bugnini is odd, as the reform went far beyond the text of the Constitution, and likely beyond what most of the Fathers of the Council had in mind. (As part 2 of ‘Mass of the Ages’ points out). The Pope’s optimistic hopes seem Pollyannish in retrospect, and the practical proscription of the ‘Old Mass’ – which was never explicitly abrogated, as Pope Benedict makes clear in his 2007 Summorum Pontificum – is also opaque. Liturgical abuse, iconoclasm, destroyed altars and sanctuaries, jejune translations – wreaked much harm, and to this day one wonders what the Pope was thinking, as he prayed in the midst of the Vatican. There are stories told of cardinals entering his office, to find the beleaguered Pontiff weeping on his desk, with stacks of files from priests requesting laicization, things spiraling out of his control.

Whatever one thinks of the decisions of Paul VI, somehow, we trust, in the midst of all the turmoil, God led him to holiness, which is not to be found so much in what we do, nor in the effects of our decisions, but who we are, before that same God, in all the travails, exterior, but more so interior, that assail us.

Ora pro nobis, Giovanni Battista, Paolo VI.