John Stansifer has written a fascinating and inspiring life – I could scarcely put it down – on Father Emil Kapaun, an army chaplain who died in this 23rd day of May in a prisoner of war camp in North Korea in 1951. The Korean war – technically known as a ‘police action’ – was in reality a bloody, brutal battle in which thousands of Americans and Canadians gave their lives, not just in the battlefield, but in the hell of the ‘camps’ that were, in the hands of the Communist North, nothing less than slow, brutal death sentences in inhuman conditions.

We may never have heard of Father Kapaun were it not for the war. As Aristotle says, virtue is tested, and manifested, in adversity. So, it was, on the battlefield and in the camp, Father Kapuan showed himself a saint.

Emil was born on April 20th, 1916 of Czech immigrants, and grew up on a farm in the small town of Pilsen, Kansas. From the start, he chose a life of holiness, and we should be clear that such is indeed a choice, even if inspired and elevated by grace. Always of a cheery and optimistic disposition – which is also, at least in large part, an act of the will, as much as a gift of nature – Emil responded to the call to the priesthood. He proved an excellent student, gifted in languages, and set to work in his home parish. He never shirked work, and perhaps, should he be canonized, he may be adopted as the patron saint of the virtue of ‘industriousness’, which has nothing to do with our modern notion of ‘industry’. Rather, it is the virtue by which, as Saint Thomas says, has to do with fortitude, and persevering through tasks that are difficult.

Father Emil also did not shy away from adventure and duty, which often go together. In the midst of the Second World War, which the United States joined after the bombing of Pearl Harbour in 1941. Father Kapaun, as a young and fit priest, signed up and served as an auxiliary chaplain – a non military member – for two years before being commissioned as an officer and chaplain in 1945 – serving in the CBI (China-Burma-India) theater of the war. He was famous for driving in his jeep or even cycling up and down mountainous roads to the remotest locales to say Mass, hear Confessions, anoint the injured and sick, console and comfort, even at great risk of life and limb to himself.

He survived it all, and returned to the U.S. when his tour was up, completing a masters in Education from Catholic University by 1947. But he recognized that the war was not over, with the deadly threat of Communism spreading its insidious errors across the world. He reenlisted in 1948, posted to Fort Bliss, before being transferred to Japan early 1950.

It was in that year the Korean conflict began, when the Communist North invaded the South. America decided to intervene, and the call went out for chaplains to serve the soldiers being sent over. Father Kapuan, who loved his home, his parents, siblings, nieces and nephews, felt himself called back to once again offer his life for his beloved soldiers.

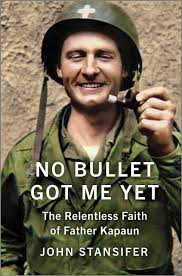

So off he went, to the cold and barren wasteland of North Korea where Father Kapaun’s sanctity was put to the ultimate test. Whatever he had suffered in Burma, was nothing compared to what he was now to go through. I won’t give away all the details, for I could do little to augment, or even summarize, the gripping details described by Stanisfer. Suffice to say that with an almost reckless disregard for his own safety, bullets whizzing around his head, Father Kapuan would boldly, even cheerfully, go forth not only to spiritually administer to the soldiers, but often hauling them out of harm’s way, on his own back. It has to be read to be believed. As he put it, ‘no bullet got me yet!’. More than once, a bullet broke in two the pipe he almost always had in his mouth – the photo on the front page of the book is iconic. Father Emile had a supernatural trust in God, that He would not let his foot trip upon a stone and that he could tread unmolested through the very valley of death, until it was his time to go.

That time did eventually arrive. Father Kapuan’s unit was surrounded. He could have escaped, but stayed behind to tend the wounded, and so was taken with the other survivors as a P.O.W. to the hellish camps. The Communist North Korean and Chinese guards put as much stock in the Geneva convention as they did in God. Food, medical care and lack of even basic protection from the bitter cold – it was a particularly harsh winter – led to much sickness and many lingering deaths. His fellow inmates, of all faiths or none, were inspired and even saved by this imperturbable priest. As a priest, Father Kapaun was in for especially harsh treatment by the Communist guards, but he was always calm, cool, and, more to the point, charitable, praying for his tormentors, offering rational responses to their arguments for atheism. He would give away everything, and was a famous scrounger, able to find what he and his fellow prisoners needed amongst the scraps and detritus. As well, with his work on the farm, Father Emile could build or fix almost anything, from pots and pans, to tools and knives, pipes and shovels. He would secretly hear confessions and offer what sacramental ministrations he could. He was indispensable, all things to all men. The testimony was unanimous that Father Emil, from whom a supernatural energy seemed to emanate, inspired untold numbers of men not only survive, but even thrive, in conditions that would have otherwise have turned them into savages. One can only surmise how many souls he saved, not only by what he did, but by who he was.

The end came for Father Emil when, sick and suffering, he was placed in the ‘hospital’, laid on a dirt floor, and neglected. We know not much of his final hours, spent alone, but we can certain that he offered his soul to God when he breathed his last.

I myself sat in silence when I finished Stansifer’s book, and I can only recommend its reading in the highest terms. The most decorated chaplain in U.S. history, Father Emil Kapaun received the Congressional Medal of Honor in 2013 for his military valour, but had already been recognized for his holiness twenty years earlier, being declared a Servant of God by Pope Saint John Paul II in 1993. In 2015, his cause for canonization was officially proclaimed by the Vatican, with the possibility of being declared a martyr for the Faith. A major film about his life, ‘Father Kapaun’s Valley’, is currently in production, which will present an action hero who is also a saint. Without presuming upon the ultimate decision of the Church, the holiness of Father Emil Kapuan resonates through the ages. May he intercede for and inspire us all, whatever our own future holds.

No Bullet Got Me Yet

John Stansifer

Hanover Square Press

22 Adelaide St. West, 41st Floor

Toronto, Ontario M5H 4E3, Canada

HanoverSqPress.com

BookClubbish.com

ISBN-13: 978-1-335-00606-6