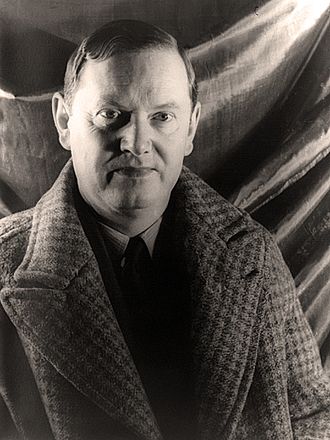

Five years after his conversion to Catholicism in 1930, English author Evelyn Waugh set his considerable literary talents – he has been described as the greatest prose stylist of the twentieth century, famous for Brideshead Revisited and numerous other works – to writing the life of the Jesuit martyr Edmund Campion, who was no literary slouch himself. You may peruse Campions ‘Brag‘ and his ‘Decem Rationes‘, his ‘Ten Reasons’ for the Catholic Faith, both written in haste, while on the run from murderous pursuants.

Campion’s feast is on December 1st, and the reader may find some details of his short and adventurous life therein in these pages. These few words are a recommendation of Waugh’s biography, for both it, and Campion’s life, speak very much to our own time. Campion was a contrarian, standing against the spiritus mundi. He could have had it all, bright, successful, up-and-coming, but threw all that way to follow Christ. Only a living thing can swim upstream, as another Englishman, G.K. Chesterton wrote, not to follow the entropic and enervating current, but show there is a far better way.

And that Campion did. Waugh’s book, to this writer’s mind, is a masterpiece of hagiography, portraying the saint as he was, in his own time, and even in his own ‘mind’, insofar as such is possible, the inner turmoil, difficulties and even doubts, as this once-foppish young man joined the most rigorous of Orders, full of their original zeal (the Jesuits were only constituted in 1540, four decades before Campion’s death). How Campion, by grace and training, was formed into an elite soldier for Christ, risking a brutal and grisly death to bring the Faith, the Sacraments, and some solace, to Catholics left bereft in Elizabeth’s increasingly anti-Catholic England.

Here is a sense of the time, and Waugh’s prose:

To the Catholics, too, it meant something new, the restless, uncompromising zeal of the counter-Reformation. The Queen’s Government had taken away from the priest that their fathers had known; the simple, unambitious figure who had pottered about the parish, lived among his flock, christened them and married them and buried them ; prayed for their souls and blessed their crops; whose attainments were to sacrifice and absolve and apply a few rule-of-thumb precepts of canon law; whose occasional lapses from virtue were expected and condoned; with whom they squabbled over their tithes, about whom they grumbled and gossiped; whom they consulted on every occasion; who had seemed, a generation back, something inalienable from the soil of England, as much a part of their lives as the succession of the seasons – he had been stolen from them, and in his place the Holy Father was sending them, in their dark hour, men of new light, equipped in every Continental art, armed against every frailty, bringing a new kind of intellect, new knowledge, new holiness. Campion and Persons found themselves traveling in a world that was already tremulous with expectation.

Waugh’s prose and powers of description – honed in his time as as traveling journalist, through war zones – are a delight and inspiration.

We are in a similar time, with a Church increasingly set-upon by the State, more and more driven ‘underground’, in various subtle ways, so far. Yes, there are differences, as history never exactly repeats itself, but oft plays the same melody in a different key, or is that the same key, with a different melody?

In our own day, the Church herself seems more and more divided, but even here, the analogy holds, for the ‘Anglicans’ in Campion’s day thought that they were the true Catholics embodying the true Church, with Campion and his Jesuits being the conservative, busybody, revolutionary radicals, upsetting their comfortable via media, and conformity to the Queen and her ministerial decrees.

Of course, in the end, like the seamless robe of Christ, the Church cannot be sundered, nor divided – the Mystical Body of Christ is ultimately one, one with her ancestors, her Tradition, her unity of truth and holiness.

We could use a ‘few good men’, like Campion, and others, like Waugh, to offer the truth for which they lived, suffered and died, to a world that is so starved for it.