Sin is complex, with multiple layers and levels. What is offered here will hopefully help discern our own moral state, as well as, to a lesser extent, what sin may signify in others.

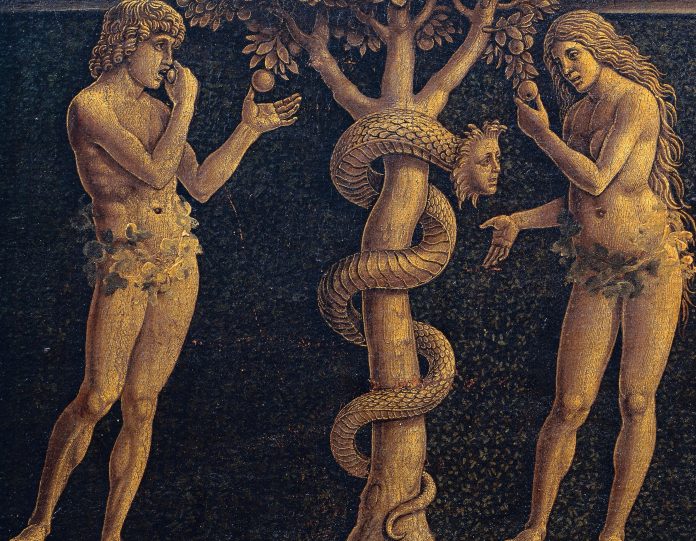

To begin, sin is a moral act, something done, or not done, in thought, word or deed. This we may call the ‘object’, the peccatum itself, what kind (or species) of act it be. Most such actions may or may not be sins, depending on one’s intention (and, to some degree, the circumstances). Certain actions, however, are what our tradition terms ‘intrinsically evil’ (instrinsice malum), which means they are of their very nature contrary to human nature, and deform us, regardless of our good intentions, or even our ignorance. These include such acts as lying, fornication and other sexual sins, blasphemy, and occultism. Basically, any direct violation of the Commandments.

Then, there is the culpa, or fault, involved in the sin. This is a defect in the will, which ‘bends’ away from the true good. We should be clear here that having a faulty will (one that is inherently bent away from the good) is not itself a sin, but does give rise to a proclivity to sin. For one can always choose not to use a faulty will, but to bend such a bent will towards the good, even if such be more difficult than having a good will, making it easier to do the good.

For the deepest level of sin is reus, or guilt, caused by the deliberate choice to use a faulty, or bent, will, or to bend a good will towards evil.

The will does not automatically act on its own. As Saint Thomas says, the will is an elicited power, which means we have to choose to use our will. That is, we must will to will.

This may seem rather esoteric to the reader, but it’s a necessary distinction to grasp, in order to examine our own conscience, and even, to some extent, discern the conscience of others, say, in confession or courts of law. Although we are far more than our will, our will does define us more than all our other powers. Behind the will, there is the ‘I’, or ego, the person who acts (as Pope John Paul II analysed in his philosophical writings).

And it is the person, who, with the will, as the words of Christ imply, chooses to love, or not to love, to will the good, or will the evil, and we are free to choose either, with fateful consequences.

Given circumstances, and other factors, our wills are often constrained, even coerced. But there is always a grain of freedom, deep down, by which we are given a choice to make. This is why in legal trials, the judge seeks to determine the mens rea – the guilty mind – of the perpetrator. How freely, deliberately, and premeditatively, did he choose the evil he did?

Of course, human courts are limited. A good sacramental confession gets closer to the mark, wherein the penitent does not hide behind lawyers and technicalities, but – ideally – opens his conscience, his own reus, as fully as he can to the priest, after a good and thorough self-examination.

The terms culpa and reus are often used interchangeably, and there is a deep connection between them. The more we choose to use a faulty will – full knowledge and full consent – the more guilty we are, and the more the will itself becomes warped, deviated from its true and proper good.

As the twelfth stanza of the Dies Irae cries out:

Ingemisco, tamquam reus:

Culpa rubet vultus meus:

Supplicanti parce, Deus.

I blush, as though guilty, my face reddens with my fault, O God, pardon the one who implores Thee!

At the end of the day – or, more properly, the end of our lives – only God can fully ‘probe the mind and heart’, and reveal the deepest secrets in our hearts, hidden even from ourselves, often mercifully so.

One of Catherine of Siena’s disciples once asked her to pray that he might see himself as he really was before God, and, when granted, he fell into a deep grief, weeping inconsolably.

With prayer, God reveals ourselves to ourselves gradually, which is why the saints who seem quite holy from any objective standard, realize more fully their own sinfulness as they grow ever-closer to the perfection of the heavenly Father.

In one of those many paradoxes of the Christian life, this should give us hope, that if we remain faithful to prayer, the sacraments, confession, repentance, trust, always picking ourselves up, forgiving ourselves and others, we will gain heaven.

But we cannot become complacent, with ourselves, or with others. There are, as Saint Paul warns, those who stop even fretting about guilt, who have deadened their conscience, seared and scarred in evil. Woe to them. As Padre Pio said to a self-satisfied penitent who claimed not to believe in hell, ‘You will when you get there’. Guilt is not primarily a feeling, but a state of our souls; it is healthy to feel it, as it is healthy to feel physical pain. Those who are numb to guilt are in grave danger of a spiritual leprosy – a fitting Gospel metaphor. Domine, si vis potes me mundare!

Sin – all those peccati we commit daily – is still sin, and, if not uprooted and repented, will inevitably warp of our wills – culpa. This will in turn lead to a deepening guilt – reus – in our souls, a path that leads to eternal separation from, and hatred of, God and the blessed, a glimpse of which we are seeing unfold before us, as the eschaton approaches.

To avoid this ultimate tragedy, we have a duty to turn away from sin and towards the good, by the grace of God; but we also have an obligation towards others, one of the spiritual works of mercy, to admonish sinners.

A final word: This is why those who support the murder of the unborn, and anyone persisting in manifest grave sin must not be admitted to Communion. (cf., canon 915, CCL). This is not to judge their ultimate guilt or reus, but rather to ensure that they, and others who may be scandalized, may avoid the eternal loss of the beatific vision, which is what life is all about.

Such is the pastoral approach, the shepherd rejoicing over one sinner who repents.