Immediately before the credits roll, a notice appears on the screen to the effect that footnotes will follow. There are some, but they flash by too quickly for even the most knowledgeable viewer to catch; for the film, fresh as it is, draws upon a host of cinematic, literary and dramatic precursors. The most obvious is a Fred Astaire movie from 1937, A Damsel in Distress. That P.G. Wodehouse wrote the script, which is loosely based on his own novel, accounts in large part for Stillman’s peculiar style. Wodehouse delivered the goods in that he wrote dialogue that sparkles even as it furthers his whimsical story lines. Stillman does the same, providing his characters with an artificial form of speech replete with a deadpan humour that the viewer must catch as catch can, as in a facetious discussion of the plural of “doofus”: “doofuses or, better, doofi.” Also, in Damsels one of the characters is actually named Astaire—but it’s “Freak Astaire,” not Fred. A “Fred,” however, does appear. Like Gwendolen in The Importance of Being Earnest, Violet, committed as she is to tap dancing, could not possibly love anyone who was not named Fred. She meets and likes Charlie who, it turns out, like the John/Ernest of Wilde’s play, has lied about his name. And not only is it “Fred”; he knows a couple of Astaire’s dance routines and in the final scene leads Violet and the other principals in a Bollywood dance number from the original Damsel movie: Gershwin’s Things are Looking Up. Stillman out-Wildes Wilde in that Violet has also lied about her name, which is really Emily Tweeter, “as in a bird.” Nothing is quite what it seems. Rose, e.g., with a plummy English accent, is from London, but only in the sense that she has come from London after a six-week visit from the States. There’s even a whiff of The Last Days of Disco early in the film, when the four heroines dance to a disco tune at a frat party.

Stillman’s affection for another genius of dialogue, Jane Austen, is evident in the heroine, Violet. She’s as bossy and arrogant as Emma Woodhouse, although her companions—Rose, Heather and Lily—are no Harriet Smiths. In fact, Violet herself, with her box of insignificant mementos of her boyfriend, the moronic Frank (Churchill?), is the more Harriet-like. But after she has been betrayed by Frank, she moves into Sense and Sensibility, wandering away like Marianne out into a storm. Again, like Marianne, she learns that it is possible for a young woman to form a second attachment after the loss of her first love. Such charming conceits, we learn in a lecture Violet attends, are in the tradition of Thomas Love Peacock and Ronald Furbank, another in-joke that directs our attention to the element of comic exaggeration that occasions much of the humour of the film, such as education students who try to commit suicide by jumping off a two-story building. A much more potent literary source, however, is Shakespeare’s romantic comedies, especially A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The impossibly stupid male students at “Seven Oaks College,” for instance, are Stillman’s versions of Quince, Bottom, Flute, Snout, and Starveling. They even put on a pageant that goes as hilariously wrong as the production of Pyramus and Thisbe in A Dream. And Shakespeare’s magical forest is well conveyed in the never-never land of an idyllic New-England college campus.

The leading ladies are sharply drawn. Violet, for all her clever and slightly absurd posturing, like Emma learns to be humble (as her name implies) after a series of disasters, including coming as a client to her own “Suicide Prevention Center.” Her treatment for depression is doughnuts and tap dancing, and she plans to reform society by starting a new “international dance craze” that, fantastically, she compares to Richard (sic) Strauss’s invention of the waltz, Frederick Charleston’s (sic) of the Charleston, and Chubby Checkers’ (sic) of the Twist. The original launching of the new dance, the Sambola!, may have been a fiasco but, like the disco finale of The Last Days, achieves its purpose at the end of the movie when everyone takes to dance floor. Like Josh, the Jesus figure from Last Days, Violet is described as unbalanced and superstitious, convinced when she was a child that her parents would die if she did not repeatedly perform a series of idiosyncratic rituals. “Was she Catholic?” Lily asks. “No,” Rose replies, with Stillmanesque ambiguity, “but her parents did die.” I wonder if the connected themes of suicide and depression were not originally suggested to Stillman by the words of Things are Looking Up: “Love’s in session/And my depression/Is unmistakably through.” Not surprisingly, I had to look up these lyrics as the song, like most of the music in the film, was unfamiliar to me. I did, however, catch two bits of classical music. The very first we hear is, appropriately, a snatch of Gaudeamus igitur. Later an aria from Bellini’s Norma accompanies Violet’s comforting the suicidal Priss. In the opera, Norma loses her Roman lover to Adalgisa, so that the sound tract is alerting us to Frank’s dastardly upcoming tryst with Priss.

Rose is a version of the Chris Eigeman character featured in Stillman’s first three films—Metropolitan, Barcelona, The Last Days of Disco—a cynic who delights in speaking the truth, the harsher the better, until with a smile she joins Freak Astaire in the final Sambola!. Heather is a non-entity who simply provides cues for the others. Suitably, her boyfriend is the thickheaded Thor. He has come to university to learn how to identify colours, a branch of knowledge that, because his parents had him skip kindergarten, he had never mastered. A rainbow panics him until, at last, the breakthrough comes, and he ecstatically names the colours one by one, irrefutable evidence of the value of a college education. Finally, Lily, the outsider, is a spokesman for us who are watching the film, in that she asks the obvious questions that tax even Violet’s power to improvise.

They are preordained for one another by their sweet-smelling names, and their campus reform is centred on getting the boors from the male dorm to bathe: “Doar Dorm will become Dior Dorm.” This scheme, based on the appeal of the scented soap that brought Violet out of her depression, fails dismally (like all the others). The boys are not as susceptible to “nasal shock” as is the floral quartet of leading ladies. At his most whimsical, Stillman employs scent as a symbol of virtue. It is unlikely that he knows Loss and Gain, John Henry Newman’s long-forgotten novel of 1848. In it, however, Newman expatiates on the special qualities of smell:

Scents are complete in themselves, yet do not consist of parts. Think how very distinct the smell of a rose is from a pink, a pink from a sweet-pea, a sweet-pea from a stock, a stock from lilac, lilac from lavender, lavender from jasmine, jasmine from honeysuckle, honeysuckle from hawthorn, hawthorn from hyacinth. . . . [T]hese scents are perfectly distinct from each other, and sui generis; they never can be confused; yet each is communicated to the apprehension in an instant. Sights take up a great space, a tune is a succession of sounds; but scents are at once specific and complete, yet indivisible. Who can halve a scent? they need neither time nor space; thus they are immaterial or spiritual.

“Immaterial or spiritual”: the metaphorical use of scent is everywhere implied in Damsels: the odour of sanctity, in good odour, a “sweet-smelling sacrifice to the Lord,” the sweet smell of success, “I smell a rat,” and even—given Violet’s allegiance to scented soap—cleanliness is next to godliness.

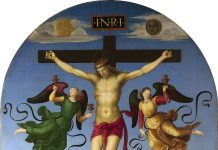

Remarkably, Stillman uses this nonsense to express a critique of contemporary society and a defence of traditional Christian attitudes towards courtship and marriage, themes we recognize from his earlier films. Lily’s consorting with the French exchange student, Xavier (a.k.a. Zavier), provides the occasion for a crucially important scene. As a Cathar, (a.k.a. Albigensian), the mediaeval dualistic sect that the Catholics—“typically,” Lily remarks—tried to destroy, he is on principle committed to avoid the conception of a child. His method for doing so, Chesterton had long before scornfully described in The Everlasting Man: “Let any lad who has had the luck to grow up sane and simple in his day dreams of love hear for the first time of the cult of Ganymede; he will not be merely shocked, but sickened.” This is precisely the reaction of a young man who gradually understands what Lily is describing: “That’s horrible! Horrible!” Similarly Fred (a.k.a. as Charlie) shows contempt for the contemporary version of “the cult of Ganymede,” which he tongue-in-cheek describes as “the decline of decadence.” These scenes are complemented by Violet’s defence of marriage on the basis of Genesis 1:28: “Increase and multiply.” Romance is still possible, and she affirms Lily’s initial interest in Charlie (a.k.a. Fred) as that magical moment of seeing someone “across a crowded room” that she will one day tell to her grandchildren. More than once in the course of the action she simply assumes that society is still Christian . . . “or rather Judeo-Christian.” The thesis of the film, therefore, could be expressed as follows: promiscuity and perversion are producing suicidal depression in the young men and women of America. The cure is to re-establish normal relationships (doughnuts and coffee) and traditional courtship (dancing). That the cure is complete we discover in the exuberant performance of the Sambola! at the end of the film.