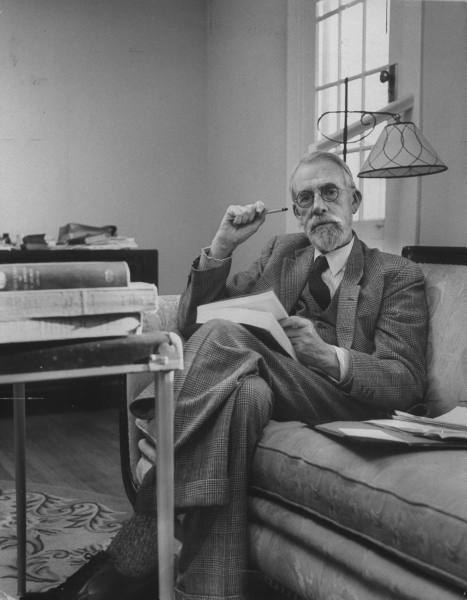

Baptized Anglican, Christopher Dawson (1889-1970) during Easter of 1909 visited Rome where he experienced a mystical event and became a Roman Catholic at the age of 25. Widely regarded as one of the premiere historians of the 20th century, his writings were greatly admired by Arnold Toynbee, T.S. Eliot, and Russell Kirk. Dawson approached history from the macro-perspective of civilizations built upon their respective religious foundations, and was particularly concerned to show that Medieval Catholicism, often disparaged by modern critics as irrelevant, largely influenced the rise of modern European civilization. The dates of his own birth and death suggest that his intense interest in historical change would likely have been prompted by the fact that he lived between the years the first automobile was manufactured and the first men walked on the moon. As Dawson remarked of his early years, “The world of my childhood is already as far away from the contemporary world as it was from the middle ages.”

One of Dawson’s great books is Progress and Religion: An Historical Inquiry (1929). As did G.K. Chesterton four years earlier in his monumental The Everlasting Man, Dawson points to the seminal rise of Christianity as an event that transformed the arc of human history: “The victory of the Church in the 4th century was not, as so many modern critics would have us believe, the natural culmination of the religious evolution of the ancient world. It was, on the contrary, a violent interruption of that process which forced European civilization out of its own orbit . . .” After the Emperor Constantine became a Christian, the mythologies of Europe’s old pagan world suddenly died. The monotheism of Christianity made it possible for these mythologies to die, since the strength of monotheism was that it recognized one true God and dismissed all others as irrelevant. Likewise, Catholic theology, which declared itself to have a universal mission, furnished a social glue that had hitherto been lacking, not to mention a moral theology much needed by a decadent and dying civilization. Two great developments were immediately inevitable following the adoption of Christianity in Europe: (1) the end of gladiatorial slaughter as entertainment; (2) the gradual decline of slavery as an institution opposed to Christian principles, especially the Golden Rule preached in Matthew 7:12.

Dawson understood very well the origins of the notion of progress that so completely dominates the modern world. “No civilization, not even that of ancient Greece, has ever undergone such a continuous and profound process of change as Western Europe has done during the last 900 years. It is impossible to explain this fact in purely economic terms by a materialistic interpretation of history. The principle of change has been a spiritual one and the progress of Western civilization is intimately related to the dynamic ethos of Western Christianity, which has gradually made Western man conscious of his moral responsibility and his duty to change the world” (italics mine). Dawson asserts that the very idea of Progress, therefore, is rooted in Christian theology: both the inner progress of the individual soul toward spiritual salvation, and the outer progress achieved by religion’s contribution to social stability and justice. The first significant modern expression of the doctrine of progress, The Plan for Perpetual Peace, was proposed in the 18th century by the Catholic priest Abbe de St. Pierre. The proposal was later advanced by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and progress for two centuries was identified in politics as the thrust toward the collective peace of Europe by way of the organization of states, the most recent expression of which has been the United Nations, which expanded world peace as an aim to embrace all nations.

II.

All this perhaps puts the cart before that proverbial horse. Something simmered for centuries below the surface of philosophical and theological thought that dominated medieval Europe; that something was a reaction that was bound to set in against the dominance of the medieval schoolmen, the profoundly influential theological heritage of the thirteenth century represented in the works of Albert the Great, St. Bonaventure, Duns Scotus, and most of all St. Thomas Aquinas. Perhaps the two reactions that were most seminal were those of the Franciscan intellectuals William of Ockham and Roger Bacon. It is significant that Bacon, who espoused the empirical method of reasoning about nature, was a contemporary of Aquinas; and that Ockham, who was born not long after the death of Aquinas, developed the scientific principle now known as Ockham’s Razor. In any case, it is from their appearance on the European cultural scene that we can begin to mark the long and steady trek of scientific thought through the centuries to its first remarkable eruption in the minds of Copernicus, Galileo, and Newton. A close examination of the personal biographies of these three will show that while modern science had begun to flex its muscles, it had not yet flexed them to do battle with religion. Copernicus (a Catholic priest) and Galileo were Catholics; Newton was a dedicated theist and student of Biblical prophecy; some of his predictions, especially those relating to modern Israel, were remarkably on target. Above all it is significant that the application of mathematics to natural laws was the greatest breakthrough in science, and that this breakthrough could never have been imagined by the medieval theologians.

As science progressed, so did technology, its proudest and boldest child. It was not long after Newton that the Industrial Revolution began to impact the idea of Progress both among the intellectual elites and the masses.

“The doctrine of Progress in the full sense must involve the belief that every day and in every way the world grows better and better…. A new industrial-scientific type of civilization, entirely unlike anything that has existed at any earlier period of the world’s history, has made its appearance, and this has led to a vast increase in wealth and population and to the world-wide expansion of European culture. At the time of the Renaissance, Europe was still hard pressed by the forces of Islam, and the Mediterranean was in danger of becoming a Turkish lake…. All over Europe, and in the new lands of the European culture across the seas, the old forms of government were giving place to democratic institutions .… Finally, the great humanitarian movement has destroyed slavery and swept away the barbarous punishments which are almost as old as civilization, while the introduction of universal education has entirely transformed the intellectual life of the masses.”

With such developments, it was seemingly inevitable that the doctrine of Progress should become absolute to any thinking person. So thought the British anarchist William Godwin, who insisted that when the future utopia arrived, “In that blessed day there will be no war, no crimes, no administration of justice, as it is called, and no government. Besides this, there will be neither disease, anguish, melancholy, nor resentment. Every man will seek with ineffable ardor the good of all.”

But, Dawson reminds us, the doctrine was delusional. It was built upon a false assumption: that religion was little more than centuries of primitive magical notions. Religions and the moralities that flowed from them were viewed as ephemeral because they varied from person to person; whereas, because science was built upon universal truths, Progress was more likely to flow from science than from religion. There was, from the start, the simple-minded notion that science and technology would end all the problems of the world in the course of time. And so the idea of inevitable Progress was born. Scientists set aside morals as an issue they were not concerned to address; moreover religion, especially Christianity, was viewed by many as the “dark power which is ever clogging and dragging back the human spirit on its path towards happiness and progress.” It was inevitable that sooner or later Progress would outstrip morals (as indeed the scientific progress toward nuclear weapons outstripped the notion that utopian peace produced by science was just around the corner). The baneful consequence of the doctrine of Progress was that, “The religious and the scientific traditions remained apart from one another, and each hampered the other in the attainment of its full development.”

III.

The rise of the 19th century socialist movement, of which Karl Marx was the chief visionary, played right into all this optimism about the inevitability of progress. Marx made religion not only irrelevant, but replaced it with himself as Moses leading mankind to the Promised Land. Here is his description of that land.

“For as soon as the distribution of labor comes into being, each man has a particular exclusive sphere of activity, which is forced upon him and from which he cannot escape. He is a hunter, a fisherman, a shepherd, or a critical critic and must remain so if he does not wish to lose his means of livelihood; while in communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, to fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticize after dinner, just as I have in mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, shepherd or critic.”

We know how completely that utopian vision of Progress failed with the fall of the Soviet Union after seventy years of trying it out.

Perhaps no scientific discovery did more to accentuate the doctrine of Progress than Darwin’s theory of evolution. Progression through time from simpler to more complex and more superior life forms brought into doubt the creation account of Genesis. But since Darwin’s day, no scientific theory, with the possible exception of Freud’s discoveries, has done more to drive a wedge between religion and science. Agnosticism and atheism began their pernicious spread almost immediately, and even to this day notable biologists like Richard Dawkins are content to point to evolution as a theory that made the spread of atheism intellectually respectable and even a symptom of progress. Darwinism as such did not do that, of course, since even Darwin denied that he was an atheist. The truth is that the doctrine of Progress (change for the better) carried within it the denial of anything permanent. Therefore certainly the eternal truths of religion and even philosophy had to become the main target of the advocates of Progress. This was the genesis of the 19th century science of sociology, which abrogated to itself the old functions of religion and philosophy. The new science of Sociology and its greatest advocate, Auguste Comte, was to become the science that we might today call the Theory of Everything, in that it coordinated and integrated all the earlier sciences to reflect a myopic scientism. This was reflected in its self-conscious mission, to study societies as products of a mechanistic and materialistic process evident everywhere in the universe. But Comte became self critical of his own views and instituted more aggressive trappings for them by elevating his philosophy to a religion of humanity as opposed to a religion of God.

For all the above reasons, in the West religion began to die and secularism was born and nurtured to its modern triumphs. Rousseau’s belief in the perfectibility of men born in a state of innocence had been carried forth with touchingly naive innocence, at least until the French Revolution, when it was manifest to all who escaped the guillotine that man’s fundamental innocence is not so definite as Rousseau would have us believe. The old Christian doctrine of original sin and the need to be cleansed over and over by the pure waters of baptism and faith began to resurface as a contender with rank scientism. In spite of the arrival of marvelous inventions such as the automobile and the airplane, World War I increased the skepticism that man is perfectible, and increased also the skepticism, after the invention of ghastly weapons of death and destruction, that science and technology were the means to a final utopia. It came to be recognized once more, as the Church of old had preached, that there were more devils in the details than anyone had ever suspected, and that these devils needed something more combative than the instruments of mere science and technology to tame them. This explains why Auguste Comte began to advocate adopting for the science of sociology the trapping of a religious movement, sometimes referred to as the “religion of humanity.” Comte invented a motto for his movement: “Love as a principle and order as the basis; Progress as the goal.”

IV.

Dawson in his next-to-last chapter, “The Age of Science and Industrialism: The Decline of the Religion of Progress,” examines the critical role of England in establishing the principle of progressive liberalism. England, after all, was the heart and soul of the Industrial Revolution. It was there that the philosophical influence of Newton, Bacon, Locke, and Hume was most keenly felt. It was there that utilitarianism and Unitarianism, step-children of the earlier Deist movement throughout Europe, reached their fullest development and success. It was there that monarchy became a mere memory or a shadow of its former grand self, and parliaments full of shouting demagogues ruled the new democracies. It was there that capitalism and its dynamic methodology … competition … transformed England from an agrarian system to a factory empire that ruled the world through a new system of transportation, the railway, a system England pioneered and that dwarfed the famous ancient highways of the Roman Empire. It was there that the willing acceptance of change, the grass root principle of liberalism, took hold and grew like a prairie fire throughout Europe and North America.

As inventions displaced inventions, and institutions displaced institutions, the idea of social stability so common to medieval agrarian Europe began to disappear. The individual who had gained the right to vote now began to realize that his vote mattered very little in the rapidly changing market of goods and ideas that had been produced by the few and imposed on the many. The congregation of millions in large cities made men feel more like ant colonies than free spirits. The growth of poverty and ignorance among the masses, the population explosion accompanied by dwindling food resources, the dizzying whirl of machinery and belching of smokestacks, the ever changing fad of fashions, the obscene exhibitions of wealth, the cruelty of child labor, the crushing materialism of frenzied stock markets, and the receding influence of religion along with increasing lawlessness, left many pining for the world that used to be. Then the scientific/technological supremacy of Europe, as it spread westward and eastward and worldwide, came to be challenged. Even the world of Islam, that had been left behind and was no longer a threat to the West, was coming back into its own as a mighty engine of military progress, just because it was able by oil production to purchase the weapons made in the West to use against the West. So, was all this really progress, or was it reason to believe that on balance the world was lurching toward regress as much as progress? Indeed, would progress become a religion against which the world would come to rebel, as it had once rebelled against the old religions?

The industrialization of the world is having a profound effect of the nature of the human condition itself, Dawson observes.

“Even in the countries where agriculture retains its economic importance, the peasant no longer preserves his separate way of life, and all the powers of the state and of public opinion, acting through politics and the press, standardized education and universal military service, co-operate to produce a population of completely uniform habits and education. Modern urban civilization no longer has any contact with the soil or the instinctive life of nature. The whole population lives in a high state of nervous tension, even where it has not reached the frenzied activity of American city life. Everywhere the conditions of life are becoming more and more artificial, and making an increasing demand on men’s nervous energies. The rhythm of social life is accelerated, since it is no longer forced to keep time with the life of nature. This complete revolution in the conditions of life must inevitably have a profound effect upon the future of mankind. For it is not merely a transformation of material culture, it involves a biological change which must affect the character of the race itself.”

Dawson wondered whether the progressive thrust of science will be strong enough to save us from ourselves. He wondered whether it was really inevitable that science would have the power to correct its own “progressive” mistakes. Were he living today under the threatening clouds of nuclear holocaust, he would have even more cause to wonder. Was the so-called “progress” of military might in Nazi Germany merely the foreshadowing of a wilder and more dangerous insanity yet to come, one aptly dubbed MAD (Mutual Assured Destruction) between civilizations as great as the West, Russia, China, and even lesser civilizations today in Iran and North Korea?

V.

For Dawson the old spiritual unity that Christendom had provided was a thing of the past, to be replaced not by a new unity that provided answers and comfort to troubled souls, but by a plurality of opposing philosophical systems, most of them rooted in a secularist agenda of materialistic atheism, which provided neither answers nor comfort, but more so a universal anxiety that persisted in draining the life of the spirit. The careful nurturing of this life as a preparation for the next one became a careless nurturing of this life as a preparation for nothing beyond the grave. The world was becoming aware of itself as an endless recycling of dust to dust, as Nietzsche reminds us constantly in his Joyful Wisdom published seven years before his mental breakdown. Nietzsche imagined himself a prophet predicting the death of Man and the birth of the Superman. This flat-lined science-fiction spirituality (exploited in several of Bernard Shaw’s plays) found yet another consummation in T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland, written during the period of Eliot’s own nervous breakdown just seven years before the publication of Dawson’s book on Progress. Though Dawson could not yet know it, the forthcoming atheistic ennui and despair celebrated in the existentialist novels of Sartre and Camus was barely a decade away.

The denial of immortal life necessarily implied the necessity of choosing to live life to the hilt, whatever that means, even if it means triumph by tooth and claw (since there is no God to insist otherwise). Contemporaneous with the decline of spiritual unity was the rise of scientific unity, a united assault by mechanistic science on the life of the spirit. Marx himself ironically viewed the laws of history, which would free men ultimately from their slave impulses, as mechanical laws since they were subject to blind necessity. It must have registered in the minds of at least some of Marx’s disciples, that the inevitable economic laws of communism (without a benevolent Deity to guide them) might just as well produce inevitable misery as inevitable utopia. But since Marx believed no more in the Devil than in God, it of course would not occur to him that Communism might be as Satanic as any philosophy the world has seen, as it later proved to be.

But, Dawson concludes, modern science (especially physics) has thrown a monkey wrench into the old deterministic model for the laws of nature. Modern physics has shown that the universe had a beginning and is slowly running out of energy as it “progresses” toward its ultimate end. This is anathema to the Progressive spirit of the 19th century which assumed inevitable and endless progress toward some far-off but as yet unknown climax. It is also an uncomfortable reminder of the Biblical language regarding Alpha and Omega. Who or What is in charge of this awful and majestic unfolding of the universe that starts like an arrow shot from its bow and ends dead-on its target, homo sapiens? And why is there a creature called Man who knows this happened as it did? Though the Big Bang theory had yet to make its way into scientific respectability when Dawson wrote Progress and Religion, by the time he died in 1970 he would have seen the vindication of his view that science and religion could find some common ground, at least in the first chapters of the Book of Genesis.

VI.

Dawson offers a stern warning about the future.

“We have entered on a new phase of culture – we may call it the Age of the Cinema – in which the most amazing perfection of scientific technique is being devoted to purely ephemeral objects, without any consideration of their ultimate justification. It seems as though a new society was arising which will acknowledge no hierarchy of values, no intellectual authority, and no social or religious tradition, but which will live for the moment in a chaos of pure sensation…. We are only just beginning to understand how intimately and profoundly the vitality of a society is bound up with religion. It is the religious impulse which supplies the cohesive force which unifies a society and a culture. The great civilizations of the world do not produce the great religions as a kind of cultural by-product; in a very real sense the great religions are the foundations on which the great civilizations rest. A society which has lost its religion becomes sooner or later a society which has lost its culture.”

According to Dawson, the great mistake of the “Religion of Progress” was that it centered only on the world that is exterior to the self. In that centering it succeeded marvelously on its own terms, as the Age of Inventions and Convenience has proven. But its own terms were not the terms that provide the discovery of ultimate truths and inner peace. In proportion as religion has receded into the shadows of society, or has even retreated to the point where it can hardly be found because of political suppression or deliberate neglect, the exterior world has all too clearly become a distraction from the human spirit’s need to be nurtured and satisfied according to the plan of its Creator:

“The ideal of a social order based on justice and goodwill between men and nations has not lost its attraction to the European mind, but with the disappearance of the old Liberal optimism it is in danger of being abandoned as a visionary illusion, unless it is reinforced by a renewal of spiritual conviction. For it is a religious ideal and cannot exist without some religious foundation.”

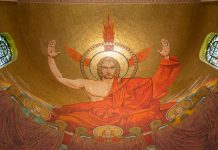

That religious foundation must be a deeply personal one, the kind that Deism and Scientism does not support. It is in the Christian religion that the heart’s desire is satisfied, because in this religion, as opposed to Deism and Scientism, the search for the absolute is made personal in the person of Jesus Christ. He alone will call to us and lift us to holiness. Deism and Scientism cannot even pretend to do any such thing.

If progress without religion is a fatal illusion, which is an argument that can be made with increasing credibility today, the return to religion is more compelling a necessity than ever. “We have come to take it for granted,” Dawson concludes, “that the unifying force in society is material interest, and that spiritual conviction is a source of strife and division. Modern civilization has pushed religion and the spiritual elements in culture out of the mainstream of its development, so that they have lost touch with social life and have become sectarianized and impoverished. But at the same time this has led to the impoverishment of our whole culture.”

The test of whether Dawson’s thesis has true merit is to look at the way of the world, the flesh, and the devil from when he wrote in 1929 to the present. Anyone born that year and still living is likely to acknowledge a general collapse of Western morals due very largely to the breakdown of religion and the absence of moral uplift that flows from religious conviction. Communist and socialist progressives worldwide have contributed greatly to the free-fall of Christianity, as any student of history can see happening in Europe and Scandinavia over the last hundred years.

There is no more convincing evidence of the false promise of Progressives than the rise of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (Communists) in the 1920s and the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nazis) in the 1930s. Both were godless socialist movements that promised material progress and utopia. Both plunged the world into a universal madness from which we are still recovering, except that today the bulwark of religion is even weaker to oppose socialism than it was in the 20th century. Sadly, we know that socialism has found many allies among modern religious leaders who refuse to understand that socialism is inherently totalitarian; socialism seeks ultimately to overcome religion altogether, just as the Chinese government seeks to overcome the Catholic Church in China today, and just as recent trends in the United States strongly indicate that Progressives intend to impose their secularist moral vision on American Christians.

But finally, as to the rabid and relentless pursuit of material progress, we have heard it said by the One who preaches truth: “For what does it profit a man to gain the whole world and lose his soul?”