It is winter in Saskatchewan. My dad, brother, and grandmother came from Ontario back in mid-November to visit for the first time since I moved here. They found themselves with snow already on the ground and a stiff chill in the air. There aren’t a ton of tourist activities in Saskatchewan, with an acute shortage in the off-season, so we explored the Western Development Museum’s Saskatoon location. A life-sized replica of a 1910 prairie town covers much of the museum’s square footage, with buildings and antique items from the period bringing the early years of Saskatchewan to life. As much as I enjoyed wandering through this section with my family, I wasn’t impacted by it nearly as much as that of a steam tractor.

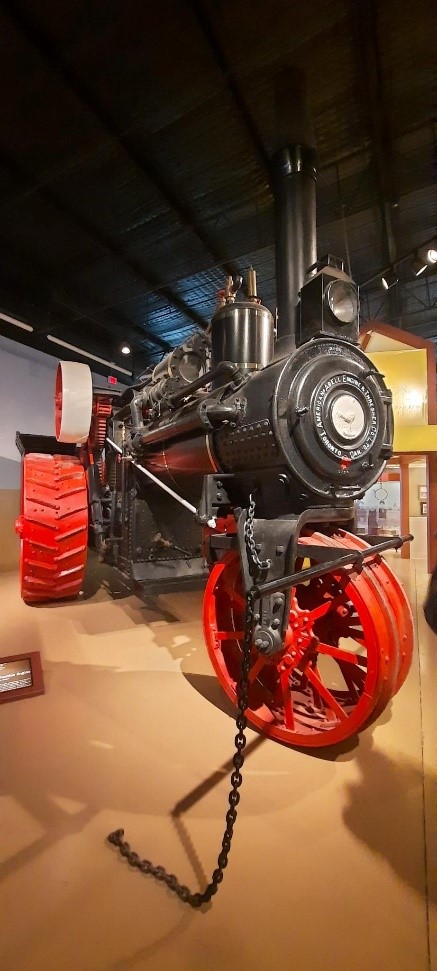

That is, is a large American-Abell steam tractor from 1911. It stands some twelve feet in height to the top of the smokestack, and while its sheer size is impressive, that is not what struck me so deeply. This steam tractor is beautiful. With its large red wheels, white lettering and flywheel, and brass bands around the boiler and cylinders, there is a beauty to this monumental machine. I was both struck and perplexed by this. Why would such a utilitarian object be so beautiful? In 1911, the farmers on the Canadian prairies were typically poor, many of them Eastern Europeans who escaped the old world, revolution and bloodshed at their heels, with few, if any, belongings to bring to the new world. There is no practical purpose for a tractor to be beautiful, and yet, this one is. As I continued to explore the museum, and I noticed that it wasn’t simply this steam tractor, but all of the farm implements, right down to a one furrow plow, which had some decorative elements, most often in the paint job, but sometimes with cast eagles, as on the Case-brand equipment. Why did the tractor manufacturers of the early twentieth century care to have beauty within their machines?

As I continued around the life-sized replica of 1910 prairie town after having this realization about the steam tractor, I felt something strange which I couldn’t quite explain. I’m not a Welsh speaker, but I’ve run across the word hiraeth before in past online rabbit holes. There’s no easy way to translate hiraeth into English, but it is akin to homesickness or nostalgia, but with a sense of unattainability, because that which you long for cannot be retrieved.

A certain level of beauty permeated all aspects of the 1910 replica town, regardless of whether its use was practical, like the steam tractor, or for the impractical, such as the ornate women’s hats in the general. This fact was inescapable as I wandered around. Nothing was truly plain, including the most utilitarian objects. The sense of hiraeth that overcame me was accompanied by a sense of grief, which is also part of its definition. It occurred to me that we live in an ugly world, in a culture that is wholly unlike that which built a beautiful 26.5-ton steam tractor. The pop music which assaults us in the grocery store is neither popular (in the original etymological sense, from the Latin popularis “belonging to the people”) nor edifying, instead distracting by design, and manufactured. So much of contemporary visual art, classical music, and poetry all tend toward chaos and discordance, evoking chaos, even evil, and not order, which itself mirrors God and the natural law. Modern architecture especially is repugnant, with a building’s utility trumping all possible notions of beauty, order, or harmonious proportion, instead replaced with academic fetishes like brutalism and deconstructivism. Old Toronto City Hall and the New Toronto City Hall are so starkly contrasted, it is clear that different cultures built these two civic structures.

Christianity has ceased to be the glue that binds our society together. The more I ponder this fact, the more I realize that our culture is no longer has the last flickers of Christendom, but something else – for the barbarians are no longer outside the walls of the city, but inside. What are we to do in the midst of this cultural collapse? It is clear that the world is starved for beauty. When constantly surrounded by ugliness in sight and sound, our souls cry out for something more.

While in the first year of my undergraduate studies, a friend and I stopped at St. Theresa’s Parish in Ottawa while on our way to get supper nearby. I needed to return some music, so I walked up the nave and back again, while he stayed in the narthex. The friend, with whom I’ve since lost contact, was an atheist, and never ventured beyond the main arch of the narthex. He was unusually quiet after we left. I finally asked him what was on his mind, and he replied, “that place was holy.” Holy is not a word typically found in an atheist’s vocabulary, and I hadn’t prompted him with questions about what he thought of the church. Something about the beauty of the space struck him in a way he couldn’t explain.

This brings my thoughts back to the steam tractor. Its simple beauty speaks to a world of order, proportion, and perhaps even holiness. But how, and why? Why does this tractor matter? Teacher and author Dan Millette brought a recent story of American author and farmer Wendell Berry to my attention which illustrates this.

In Berry’s recent collection of fictional stories, How it Went, there is a scene where an old farmer is forced to hire a college student to help remove brush and branches from a repaired fence line. The old farmer grows frustrated that the young man– a music student no less –is throwing the branches onto the wagon in a disorderly fashion. The old farmer then speaks up, revealing that even loading brush is a way of beauty, and a beauty worth preserving:

“And in my opinion, if the art of loading brush dies out, the art of making music finally will die out too. You tell your professors, when you go back, that you met an old provincial man, a leftover, who told you: No high culture without low culture, and when low culture is the scarcest it is the highest. Tell’em that. And then tell me what they say” (p. 155).

No high culture without low culture. No symphonies without orderly stacked brush. And, if I may be so bold, no revival of the Church or the world without beautiful tractors.