A recent article in First Things by J.D. Flynn reflects upon Shusaku Endo’s 1966 Japanese novel Silence, now being released as a film directed by Martin Scorcese (which should tell you something). The tale follows an idealistic Jesuit missionary who, towards the end of the story, well, in Flynn’s words:

At its pivotal moment, Silence’s protagonist, the Jesuit missionary Sebastian Rodrigues, faces a terrible choice: He can hold fast to orthodoxy, or he can repudiate it and thereby alleviate the serious, immediate, and temporal sufferings of a people he has come to love.

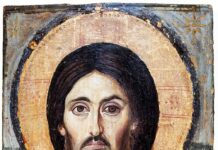

Basically, Rodrigues must choose between apostasy, renouncing his faith by stamping upon the bronze fumie, an image of Christ made by the Japanese persecutors for this very purpose, and allowing many others to suffer a horrific and slow death. After surviving his own torture with well-disciplined Jesuit fortitude, Father Rodrigues apostatizes when faced with the suffering of the beloved people he has come to evangelize.

Flynn does an admirable job explaining how Silence was a prophetic book, adumbrating in the confused tumult of the mid-sixties our own comfortable, confused culture, even of certain elements of the Church which, all too often, do not want to confront us with the full reality of our sin, so that we can be healed and “go and sin no more.” G.K. Chesterton, in a brief essay on the rather eccentric, but terrifying and harsh Dominican preacher Savonarola, has this to say:

[T]he most desolating curse that can fall upon men or nations … has no name, except we call it satisfaction. Savonarola did not save men from anarchy, but from order; not from pestilence, but from paralysis; not from starvation, but from luxury. Men like Savonarola are the witnesses to the tremendous psychological fact at the back of all our brains, but for which no name has ever been found, that ease is the worst enemy of happiness, and civilisation potentially the end of man.

Now, I admit, there is a great gulf between desiring an “easy life” and being confronted with horrific torture and death, but they have this in common: The seeking of a carefree path to heaven without the cross. God does sometimes ask hard things of us, but he also gives the grace to endure and overcome. There is no such thing as an irresistible temptation, nor of a suffering that necessarily leads one to despair, and giving up. As I have written before, it is the constant and firm teaching of the Church that moral evil must be resisted even to the point of death, and not just one’s own death, but the suffering and death of others, even of those we love. Hard words, but true. As the Catechism puts it, moral evil is “incommensurably more harmful than physical evil” (#311).

Blessed Cardinal Newman, from chapter 5 of his Apologia, describes this doctrine thus, in a way that I would presume the “world” will never get:

The Catholic Church holds it better for the sun and moon to drop from heaven, for the earth to fail, and for all the many millions on it to die of starvation in extremest agony, as far as temporal affliction goes, than that one soul, I will not say, should be lost, but should commit one single venial sin, should tell one wilful untruth, or should steal one poor farthing without excuse.

As the great Cardinal says, one venial sin, to say nothing of the total repudiation of the Catholic faith in its entirety by the sin of apostasy.

Yet, some would have it otherwise. To gain a glimpse into such a confused, syncretic, modernist mindset, here is what one commentator had to say in response to Flynn’s analysis:

I believe your interpretation of this moment is somewhat reductive. Rodriguez, by his apostasy, removes himself from the Western, imperialistic Christianity and fully identifies as a Japanese, complete with the outside/conformist vs. inside/true-self dichotomy of the culture; from that place, he begins to minister successfully. Love demanded that identification, and Christ’s grace was sufficient, not for a western hero, but for a fully broken and humiliated man.

I am not arguing this is perfect theology, only that this is where Endo takes us in Silence, to a place where, like in Pastoral matters, neither of the two options is fully good nor evil. Rodriguez’s apostasy in the book is, paradoxically, his greatest act of faith.

“Not perfect theology” is a bit of an understatement. Have we come so far in our emotionally driven theology that some now consider apostasy an act of faith? How to jibe such a view with that of the countless honor roll of martyrs? Would they have been better off just to burn the incense before Zeus and Aphrodite?

As Rodrigues contemplates his fateful decision, hearing the cries and moans of those being tortured, Christ “breaks the silence,” whispering to the priest:

You may trample. You may trample. I more than anyone know of the pain in your foot. You may trample. It was to be trampled on by men that I was born into this world. It was to share men’s pain that I carried my cross.

Hmm. I am not sure what Endo intended by this intervention, for this seems more temptation than counsel, akin to what Eve heard on that fateful, misty morning in the Garden. I wonder whether Thomas More heard a similar voice while he sat in the Tower, as King Henry’s ministers cajoled him into signing the declaration that would make the potentate ‘Head of the Church in England’: ‘Sign, sign, for what, really is a piece of paper and ink’? And the Church of England? Will the realm, and your very soul, not survive one man’s signature, and one king’s hubris? Just sign the damnable declaration, let Henry have the Church in England, what business is it of yours, and get thee back to Chelsea, where thou mayest do further good; eat, drink and be merrye with thy wife and children, and die an old man in your bed, yes, why, yes, just like Richard Rich.

The good English martyr must be rolling in his grave, or what nameless grave into which they unceremoniously dumped his headless body. Putting your foot on a holy image or signing a document are, like all of our words and actions, at one level, just physical acts, but Thomas More and the rest of the martyrs from Saint Stephen onwards were well aware that such actions signify something far deeper: our relationship with Christ, with his Truth, with God all by means of our own conscience, which “witnesses” to the truth we have accepted or rejected. Thomas knew well enough that his soul was worth far more than his head, and if the cost of the latter were the former, well then, off his head must go. Although he wanted to serve both his King and his God, if they conflicted, he was God’s good servant first. Orthodoxy and orthopraxy, right belief and right action, go together harmoniously, or fall apart miserably.

Contemporaries say that the only time another Thomas, the almost-always-implacable Thomas Aquinas, got visibly angry was in response to his contemporary Siger of Brabant, who held the Islamic Averroistic “double truth” theory, that something could be “true” in the realm of faith, while “false” in the realm of reason and philosophy, sort of an early, proto modernism. Thomas challenged Siger to a public debate, rebuking him for misleading “children,” the young gullible students at Paris, while refusing to argue with real men and real truth.

The principle of non-contradiction, Thomas declares in his Summa (I, q.15, a.4), perhaps with Siger’s confused and pernicious philosophy in mind, binds even God (if we can put it that way), who, as pure Being and pure Truth cannot violate his own nature.

There is a moral equivalent of the double truth theory, current in modern theology, that one can be “holy” in the midst of deliberate grave sin. On the contrary, apostasy, and, we might add while we’re at it, other serious sins such as heresy, fornication, lying, adultery and homosexuality and a few other unmentionables, if engaged in deliberately and willingly, put oneself more or less outside the Catholic fold. Such, as Saint Paul declares, will not inherit the kingdom of heaven (1 Cor. 6:9). Of course, there are difficult and complex situations wherein subjective culpability is opaque and lessened due to coercion or ignorance, but even here such actions are ultimately harmful to our souls, to our bodies, to society and even to our eternal salvation, as Pope John Paul described in Veritatis Splendor:

It is possible that the evil done as the result of invincible ignorance or a non-culpable error of judgment may not be imputable to the agent; but even in this case it does not cease to be an evil, a disorder in relation to the truth about the good. Furthermore, a good act which is not recognized as such does not contribute to the moral growth of the person who performs it; it does not perfect him and it does not help to dispose him for the supreme good. Thus, before feeling easily justified in the name of our conscience, we should reflect on the words of the Psalm: “Who can discern his errors? Clear me from hidden faults” (Ps 19:12) (#63).

Sin must be declared for what it is, notwithstanding ambiguous and au courant gut-wrenching novels and the situations, real or otherwise, which they depict. As we all gradually journey towards holiness, it is no mercy to twist or obfuscate the truth in ourselves or others, to turn sin into virtue (and vice versa), or as Nietzsche would put it, to transvalue all values, for such would only lead to moral chaos and anarchy, with, in the words of Yeats, no centre to hold things together, and a consequent “blood dimmed tide … loosed upon the world.”

We should let our yes be yes, and our no be no, for not even God can make it otherwise, and anything else, well, comes from you know whom.