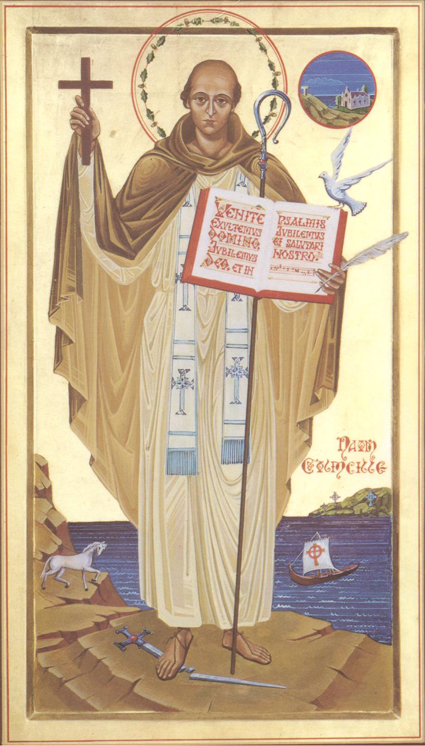

If you will forgive a little parochialism, today is the feast of Saint Columbkille (521-597), also called Columba, who is not celebrated in the universal calendar, but happens to be the patron my own diocese. He also hails originally from where my father’s family is from in Ireland: Yes, Columbkille – ‘dove of the Church’, a name he may have adopted in the monastery, was an Irish monk from Donegal on the wild west coast of the emerald isle.

(wikipedia.org)

His name does not quite fit either his historical appearance or demeanour, for gentle dove he was not, at least at first. Columbkille was described as being of imposing stature, with a strong, athletic build and a booming, melodious voice that could carry across hill and dale; he was also, apparently, an impetuous man of strong convictions, being involved, even helping to instigate, a minor war over the ownership of a manuscript he had copied from Saint Finnian, who wanted it back. An early case of copyright dispute (everything old is new again!), and those monks certainly treasured their books. The details are obscure, but a number of men were killed, for which Columbkille felt deep repentance. The saint was also involved in an apparently more legitimate struggle with the local chieftain King Diarmait over the violation of sanctuary laws.

Columbkille was going to be excommunicated, a sentence which was commuted to exile, providentially so, for he sailed across the Irish Sea in a leather boat with twelve companions, landing first at the Mull of Kintyre (made famous in the McCartney ballad), before making his way up to Iona, a beautiful, small grassy island on the west of Scotland, where he set up the famous monastery, whose ruins still stand, after its destruction under the plundering iconoclasm of Henry VIII. They have since been rebuilt, with what could be argued, lesser glory.

The abbot brought his great learning and evangelizing zeal to the task, traveling hither and yon, setting up monasteries, teaching and converting the pagan Picts, and performing miracles – legend has it that, after it had killed man, he banished a sea monster to the depths of Loch Ness, which dutifully obeyed him, and has been sought ever since.

But his life was in the main that of most monks – a daily round of prayer and work, ora et labora, which provides the seed and foundation for the kingdom. It is a testament to the foundation laid by Columbkille and his myriad monks that Scotland remained firmly Catholic until the ravages of the apostate priest John Knox, backed by royalist troops who, by fire and sword, swept the land almost clear of the true Faith.

As one account has it, Columbkille foretold the island’s glory as well as its desolation when instead of monks’ voices there would be the lowing of cattle, but the saint also prophesied that ere the world come to an end, Iona shall be as it was.

We’re still waiting for that day, but the stones do cry out. Samuel Johnson, the great writer who inherited that Protestant tradition, visiting the island 200 years after the Reformation, wrote ‘that man is little to be envied…whose piety would not grow warmer among the ruins of Iona’

I can personally attest to the truth of Johnson’s words. On a personal pilgrimage to Iona years ago, I made my way over the grassy isle to the very beach where Columbkille may have landed; looking down, I noticed all the stones were of a curious emerald green tinge, and had this thought – Irish as I am – that they turned that colour when Columbkille and his monks set foot upon the shore.

Columbkille was a missionary, a diplomat, a poet and, all in all, a saint, his early Gaelic temper apparently tempered, so that his reputation for holiness went far and wide. He rarely left Scotland, only twice, and, after a long and productive life – he lived to 75, a rarity in those days – he died on this day in 597, and was buried in the abbey on that green jewel of Iona where he had spent most of his life.

Both Scotland and Ireland need a good dose of re-evangelization, but the seeds of the faith, even in the very bones and relics of all those priests, monks, nuns and laity who carried the Faith for all those centuries until the rupture and upheaval of the ‘Reformation’. But there is hope that what once was can be again, even if only in a small, hidden way. That is how the Faith began, and that is how it may well be in the end.

We will leave you with the Altus Prosator, a 6th century hymn attributed to Saint Columbkille:

|

Altus *prosator, *vetustus |

High creator, Ancient |

Saint Columbkille, and all Irish and Scottish saints of yore, orate pro nobis!