Things are, shall we say, fractious in the Church, when an Irish priest likens receiving Communion on the tongue to ‘feeding animals’, while the bishop of Charlotte forbids altar rails and discourages kneeling. Latin and chant are almost non-existent outside a few refuges. Liturgical aberrations, if not abuses, great and small, abound.

Yet what is the answer? Retreat to the SSPX? Kennedy Hall, who has positioned himself as perhaps their foremost apologist, even goes so far as to personally canonize Lefebvre, comparing him to John the Beloved. Much does depend on one’s perspective or, more to the point, on the principles from which one begins, for the SSPX debate is about far more than the Latin Mass, or ecumenism, or even Vatican II, but the very structure and being of the Church herself, the core of her ecclesiology.

Specifically, behind all the canonical and historical arguments, all the claims of ‘necessity’ and ‘state of emergency’, everything hinges on ‘by whose authority’, as R.H. Benson titled one of his books in his trilogy on the Reformation.

The Church is a complex reality, natural and supernatural, but also hierarchical and charismatic. According to the former, she is a structure with a pope and bishops, exercising the authority of Christ Himself (but not always perfectly, and often quite imperfectly). With this structure, there are any number of ‘charisms’, each of which is a ‘gratia gratis data’, a ‘grace freely given’ to help the Church continue her mission, and grow in holiness.

These hierarchical and charismatic dimensions are meant to complement each other, even if they are often in tension. An over-emphasis on either has crippled the Church’s mission, even leading to her destruction, if such were possible.

Individual members of the Church – they need not be saints – are given these charisms, whether ordinary or extraordinary. It is the task of the hierarchy to pronounce judgement on whether or not they come from God, how they are to be supported, even brought into the structure of the Church. This is the story of the early monastic and eremitical movements; of the Franciscans, Dominicans, Jesuits; of the missionary endeavours, and every school and university, even every lay and liturgical movement, all the movements of reform and individual apostolate to our present day, unto the end of time.

Charisms do not imply holiness in the one who receives them, nor even in the one who sends them, for the devil can transform himself into an angel of light – something we should keep in mind. There are those who may have been given charisms, but went too far, thus imperilling their souls and the souls of others, and tearing the Church asunder. Such seems to be the story of Luther, who began as a zealous Augustinian, and, as Jacques Maritain suggests, had the makings of a great saint. But Bruder Martin refused to submit to the Church to which he professed to belong, trying to ‘reform’ a Church much in need of reform, but by his own authority, his own interpretation of Scripture, even by the force of his own will and personality. ‘Here I stand and can do no other’. So he stood, outside the Church, and ultimately before God in his judgement. It’s not essentially a question of ‘who is right and who is wrong’, but where authority resides. Luther may have been at least partly right, but he had no right to make himself the final court of appeal.

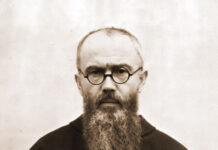

Lefebvre also had the right, perhaps even the God-given charism, to resist the liturgical chaos after Vatican II. But as we’ve written before, how far can one take this? Has the SSPX now set itself up as the final and ultimate authority of what constitutes ‘Tradition’, as Luther had done with Scripture? Are they now a parallel, if not the only, Magisterium?

The Catechism states that such gifts must always be submitted to the hierarchy, through which Christ guides His Church:

It is in this sense that discernment of charisms is always necessary. No charism is exempt from being referred and submitted to the Church’s shepherds. “Their office (is) not indeed to extinguish the Spirit, but to test all things and hold fast to what is good,”254 so that all the diverse and complementary charisms work together “for the common good””(CCC, 801).

When one reads through Lefebvre’s writings, and those of his successors, along with the current head of the SSPX, there is more at stake than what might appear. Even back in 1988, the lines were drawn: Any given liturgical mode or practice, or any document or decree, could only be deemed ‘traditional’ if Lefebvre decreed it so. Everyone was suspected of ‘modernism’ – a heresy difficult, if not impossible, to define precisely, as even Pius X admitted in Pascendi, where it is described as the ‘synthesis of all heresies’ – except, of course, Lefebvre himself and those who agreed with him.

Even if we admit, for the sake of argument, that Lefebvre was 90% right, and the hierarchical Church 90% wrong, it’s that ten percent that makes all the difference. For the hierarchical Church has a divine authority bestowed by Christ to correct error, whereas Lefebvre and his successors do not. Even if the Church drifts into aberration, her Magisterium will eventually provide correction and reform. As the barque of Peter, her temporary and provisional pilot is any given pope, but her ultimate captain and guide is Christ. He may be asleep for a time, but will awake, make all things right.

Who’s going to ‘make things right’, should the SSPX drift? Who, or what, is the principle of unity and authority? What is their Magisterium? Of the four bishops ordained in 1988, one went his own way, taking others with him, thinking the SSPX too soft and complacent and compromising. Some in the SSPX are now using the 1955 Missal, before the 1962 revisions of John XXIII. But why is Pius XII’s Mass more ‘traditional’? How far back does one go to find the perfect Mass preserved in amber? Why not 1570? Or 1270? Or even 70, and whatever Mass was said by the Apostles at the Council of Jerusalem?

I don’t mean to be facetious, nor to downplay the serious issues with the liturgical reform, but there are those in the SSPX (and elsewhere) who believe the Novus Ordo and the priests ordained therein are invalid, imperilling a billion or more souls. According to their official position, the Novus Ordo insipid and objectively harmful in the reception of grace and the pursuit of holiness. One should never attend a ‘new Mass’, even to fulfill one’s Sunday obligation, or a family wedding, baptism, funeral. They’re even loath to be present at any other traditional liturgy – FSSP or otherwise – that is not SSPX. This not only puts them in peril of breaking Third Commandment, but closes them off from the rest of the Church. Families and communities have been torn asunder, to say nothing of looming more universal schism. The road from cultus to cult is more subtle and insidious than one might think. They reject Vatican II in toto, refusing any nuance or distinction in the documents. Even perfectly scholastic terms like ‘subsist’ are derided and rejected, or that some good may be found in other religions, or any notion of religious freedom. Obedience to bishops is professed, but they set up their chapels whether or not permission is given. Do they at least give him the chance to say no? Their submission to papal authority only goes so far as their collective conscience and ongoing ‘state of emergency’ permit. But when has the Church ever not been in a state of emergency? Thus they stand, and can do no other. As one traditional priest put it to me not long ago, ‘they do whatever they want’.

Whatever one thinks of the SSPX – and I sympathize with many of their aims – we must ask ourselves whether the Church Christ founded subsists (there we go!) in the visible Church in her dioceses and parishes across the world, with her 1.3 billion members, in all of her imperfect messiness, or rather only in the ‘purified’ remnant of the SSPX, with its few hundred thousand, insofar as one may describe the SSPX as even a single entity. To use a geological analogy, if the Church is Antarctica, the SSPX is a small promontory, currently connected by a rather fragile ice bridge. Should they again take that bridge too far, will they not drift off into the mists of the South Pacific? What’s to prevent that little island from breaking apart and melting?

At the end of the day, we are faced with a choice: We are either a hierarchical Church, guided by a pope, who is Christ’s Vicar, who holds the ultimate authority. Or we are a charismatic entity of individual souls and societies, any of whom, bishop, priest or layman, may claim direct access to God and ultimate authority. Yes, the Church is in many ways a mess, but the whole point of the spiritual life is to seek perfection in the imperfection of this fractious world as we wait that final eschaton when all things will be put right. In the meantime, to paraphrase Ben Franklin, we must somehow hang together, or the devil will hang each of us separately.

My advice to the SSPX? Stay in the boat, by hook or by crook, by what minima you might. There’s no guarantee you’ll walk on water.