In response to Catholic Insight’s post of Carl Sundell’s list of 39 essential questions Catholics should be prepared to answer about our faith, I have been responding to them one-by-one to equip you with clear, concise and (hopefully) well-reasoned answers to help you grow and share your Faith.

None of these answers can be conclusive. They simplify answers and provide a framework to approach these questions. You can find links to previously published articles in this series at the bottom.

11. How do you know for a certainty that Christ performed miracles?

Similar to the opening disclaimer of the previous article about the reliability of the Bible, an apologetic for every single one of Christ’s miracles would be a task more befitting of a book than an article. Even a book that provides a comprehensive treatment one miracle of Jesus, albeit the most important miracle, spans over 800 pages! In the interest of clarity and concision, imagine this question is asked in the context of an informal conversation by someone expecting a relatively quick answer, it would be best here to focus on the reasonability of the testimony of the Apostles.

I understand that a presupposition to this question is that the New Testament itself was actually authored by witnesses or consultants to those witnesses. Suffice to say that this question has received adequate and lengthy treatment, especially in the last two hundred years when assumptions against miracles became fashionable. For a thorough yet readable treatment to the reliability of the New Testament and eyewitness authorship, Dr. Brant Pitre’s The Case for Jesus cannot be more highly recommended. If one can move beyond these assumptions and consider the sufficient evidence for the historical reliability of apostolic authorship (or consultation), then one can co spider the reasonability of the apostolic witness itself.

For this, one already has a built-in, logical application that need only be slightly modified in order to work. Many are familiar with the Christological Tri-lemma, made famous by C.S. Lewis in Mere Christianity (bk II, ch 3), that considers the claim to Jesus’s divinity. In it, Lewis proposes the three possible options when confronted with the claim: that Jesus was either lying, that Jesus was a lunatic, or that Jesus was and is Lord. He walks the reader through these options and shows that a simple reading of the evidence, the Gospels themselves, show clearly that Jesus does not speak or act like a liar or lunatic. This leaves only that Jesus was who he said he was and is who the Church continues to say he is, Lord.

The brief and simple run-through does not consider every objection that has been made since Lewis first popularized it, but it is only meant to provide a formula for how it can be paralleled to the Apostles themselves. One can apply the same liar, lunatic, “Lord” logic to the claims of those who wrote the Gospels. One need only replace the “lunatic” and “Lord” categories with the claims that the Apostles hallucinated the risen Jesus (“lunatic”) and that Jesus actually rose from the dead (“Lord”).

The “liar” option of this Tri-lemma works similar to the option concerning Jesus’s claims to divinity in the Gospels. Just like it does not follow that Jesus would knowingly die for a lie he gained nothing from, it also does not follow that the Apostles would die for a similar lie. Even scholars who are skeptical about the overall numbers of persecuted and martyred Christians during the Roman Empire do not deny that some Christians were killed because of their faith.

However, one could argue that these martyrdoms were more politically motivated than spiritually. The empire cared more about political submission than theological precision. Even if one grants this premise, one must consider why Christians were so sincere about their belief in Jesus’s divinity as contrary to the Emperor’s. It is not just a question of sincerity, as this can be present in every religious tradition, but the reason for the sincerity. One can even remove St. Paul’s witness to the Resurrected Jesus as merely a vision and must still confront the other claims of the other Apostles.

One has to ask the question of why the Apostles refused so vehemently to worship the Emperor and maintained so adamantly to worship Jesus. The best evidence we have for this “why” question comes from the Apostles’ preaching itself. One does not find the negative claims “do not worship Caesar” in the preaching of the early Church, but finds the ubiquitous call that Jesus is Lord and that Jesus rose from the dead. These claims are not mutually exclusive and, in fact, are so complementary that they are often considered a single claim by hearers. This means that the Apostles’ denial to worship Caesar was motivated by their worship of Jesus, which could not be separated from their belief in the resurrection of Jesus. So, if one accepts the sincerity of the Apostles in their martyrdom, then one must accept their sincerity in the belief of the Resurrection.

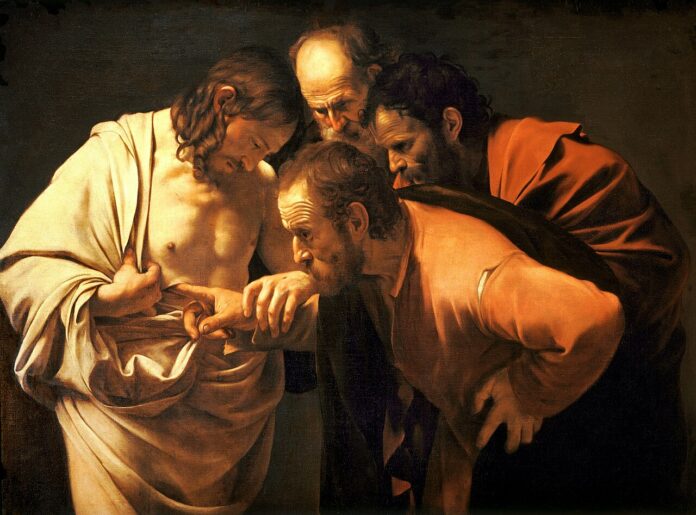

The “lunatic” claim could be applied to the still popular theory that the witnesses to the Resurrection hallucinated the appearances of the Risen Jesus. This claim is supported by documented cases of “mass psychogenic illness,” whereupon members of a community share in a collective set of symptoms tied to a stressful, though psychologically-limited, event. On the surface, one could see similarities to this phenomenon and what the witnesses “saw” together in the Risen Jesus.

However, much like the “parallels” between the Resurrection of Jesus and the pagan agriculture gods that “die” and “rise” in the Fall and Spring, upon closer scrutiny the parallels between a mass hallucination and the appearances of the Risen Jesus also do not compare. Ironically, the wish fulfilment that proponents of the mass hallucination project onto the Apostles seems to be present in the mass hallucination theorists, only now the wish fulfillment is for a natural explanation that excludes miracles. To write off the witness of the Apostles as a mass delusion is to either write off the historical record itself, the only “data” one has to go on, or to write off the actual features of the mass psychogenic illness in order to fit the eyewitness accounts in. The further irony of both of these attempts is that they themselves are in-scientific.

Similar to the principal Lewisian Christological tri-lemma, the options that the Apostles lied about or hallucinated the Resurrection of Jesus simply fall apart upon closer scrutiny. Like I said in a previous article that answered a similar question, the Resurrection itself is still, technically, an article of faith, but reason can take one very far in eliminating objections to it. This article hopefully helps eliminate the objection that is levied against the witness of the Apostles themselves about this one specific miracle. If one can accept the Resurrection of Jesus, though, the others become more easily accepted. Then, after one accepts the miracles of Jesus, the claims of Jesus, especially his claim to divinity, become more reasonable. If one can accept his claim to divinity, then one must begin to grapple with his claims to ecclesiology (“I build my Church” as Matthew 16:18 goes), but this is for a later article.

Want to catch up on the previous questions? You can find the entire series, along with Carl Sundell’s original article, here!