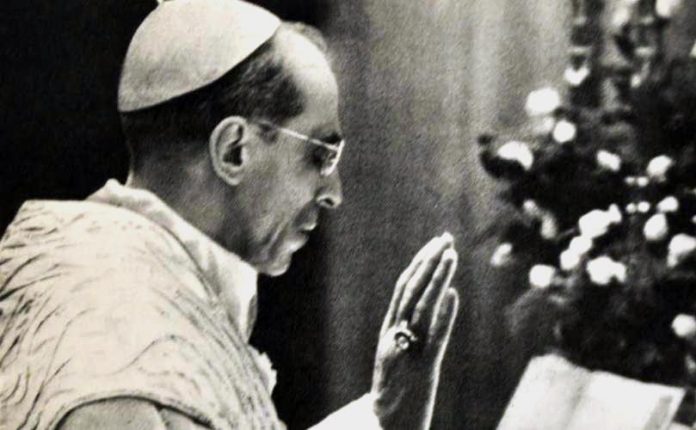

Today, October 9th, marks sixty-seven years since the death of Pope Pius XII, lovingly known as the Pastor Angelicus throughout his pontificate which spanned nearly two decades. The eighty-fifth anniversary of his election as pope (which took place on his sixty-third birthday in 1939) occurred last year. 2024 also saw the twenty-fifth anniversary of Benedict XVI’s decree recognizing the “heroic virtue” of Papa Pacelli, thereby granting him the status of “Venerable” in the persistent quest for his canonization. Despite tremendous popular support for such a move immediately after his death in 1958 (a prayer for his beatification was approved less than two months later), Pius XII has been subjected to a sort of exile since the 1960s. If he is mentioned at all in public, it is almost only in the context of the insufferably outdated debate as to whether or not he “did enough” during World War II. Indeed, such a debate seems to have obscured every other aspect of Pius XII’s pontificate.

At the same time, it may be said that the unquenchable interest in and devotion to this venerable pontiff is a sort of proof (perhaps divine proof) that the life of Papa Pacelli deserves our thoughtful attention. Leo XIV himself has made particular mention of him more than once. During his Wednesday audience of June 18, Leo quoted Pius XII’s famous appeal before the outbreak of hostilities in 1939: “Nothing is lost with peace. All may be lost with war.” Shortly before Leo XIV’s election as pope, I was blessed to attend an official commemorative mass for Pius XII organized by Emilio Artiglieri, vice postulator for the canonization process. The celebrant, Dominque Cardinal Mamberti, highlighted important documents of Pius XII’s pontificate such as his 1947 encyclical Mediator Dei regarding the liturgy, his dogmatic declaration of Our Lady’s Assumption, and his 1950 encyclical Humani Generis warning against various philosophical and theological errors. Less than two months later, Cardinal Mamberti would announce to the entire world that Robert Cardinal Prevost had been elected pope.

As noted elsewhere, the day before the commencement of the conclave which elected Leo XIV was also the fiftieth anniversary of the death of another Venerable Servant of God, József Cardinal Mindszenty. Similar to that of Pius XII, devotion to the long-suffering Hungarian prince primate has withstood the test of both time and historical-political mayhem. The close connection between the two churchmen, however, is hardly ever taken note of by the devotees of either. Nevertheless, Emilio Artiglieri, the previously mentioned vice postulator for Pius XII’s canonization, composed a moving, beautiful tribute to the relationship and heroic holiness of these two shepherds some years ago in Genoa, Italy. At that time, Ignatius Press had not yet accomplished the long-overdue republication of Mindsenty’s memoirs in English. Artiglieri’s speech, newly translated from Italian into English, is now an invitation for English-speakers to further explore the lives of these two men. Mindszenty’s memoirs are now easily accessible, and one may hope that Artiglieri’s own short biography of Pius XII may soon be available in English.

The story narrated by Aritglieri in this speech is ever timely and relevant. As he says in his closing remarks:

What remains of this whole affair? There remains the example of an intrepid shepherd, who did not fear sacrificing himself for the Church and the Fatherland through a continuous sacrifice, which, albeit in diverse forms, lasted for years. There remain the words of a holy pope, who wore the tiara like a crown of thorns, which tormented him not only during the Second World War but also during the post-war years, no less dramatic for his heart as universal father. Finally, there remains the invitation to hope, so strongly recommended by Pius XII, because hope is founded on the divine promises, the hope, which is certainty, that the most violent storms will not be able to submerge the Church of Christ.

It has been said that God wills particular devotions to take hold in the life of the Church at particular times for particular reasons. In our day, when there exists a burning desire for shepherds who fearlessly uphold the faith and the moral order against attacks on all sides, perhaps the faithful are called to earnestly invoke in prayer the intercession of these two Venerable Servants of God, Pope Pius XII and József Cardinal Mindszenty.

********************************************

Pius XII: Staunch Defender of Cardinal Mindszenty

by Emilio Artiglieri

Translated from the original Italian by Anastasia Grillo

[Note regarding the English translation: The following speech and prefatory information was originally published in Italian on the blog of the embassy of Hungary to the Holy See and to the Sovereign Military Order of Malta on June 30, 2017. Excerpts from Cardinal Mindszenty’s memoirs are taken from Richard and Clara Winston’s English translation, first published in the United States by Macmillan in 1974 and republished by Ignatius Press in 2023. Likewise, the quotes from Pius XI’s encyclical “Divini Redemptoris” are directly from the English translation on the Vatican’s website. The translation of Pius XII’s address of February 20, 1949 mainly follows the text as listed on the official English website for Pius XII’s canonization. Certain changes and additions were made in light of the translation at the blog “Rorate Caeli”, as well as that found in “His Humble Servant: Sister M. Pascalina Lehnert’s Memoirs of Her Years of Service to Eugenio Pacelli, Pope Pius XII” (translated by Susan Johnson and published by St. Augustine’s Press). The other writings by Pius XII are translated directly from Artiglieri’s speech; the full texts may be found in Italian (and, in come cases, other languages) on the Vatican’s website. Since this speech was given before the decree proclaiming the “heroic virtue” of Mindszenty in 2019, he is referred to as a “Servant of God”, not as “Venerable”. Gratitude is due, first and foremost, to Emilio Artiglieri himself for allowing his speech to be translated into English. I am also immensely grateful to Anastasia Grillo for her zealous translation and her enthusiastic support. Lastly, many thanks to Darine Abi-Karam and Allanna Donnelly for their kind and insightful edits and comments. – Joseph Donnelly]

A Celebration of Pius XII and Cardinal Mindszenty in Genoa

On June 8, 2017, a commemoration of József Cardinal Mindszenty was held at Abbazia di Santo Stefano (Abbey of Saint Stephen) in Genoa, sponsored by the Comitato Papa Pacelli – Associazione Pio XII. After mass, the president of the Comitato, the attorney Emilio Artiglieri, gave a reflection on the figures of Pope Pius XII and Cardinal Mindszenty. At the conclusion of the event, the ambassador of Hungary to the Holy See, Eduard Habsburg- Lothringen, spoke words of appreciation and thanks.

We publish the text of the speech by President Emilio Artiglieri.

* * *

Pius XII: Staunch Defender of Cardinal Mindszenty

- Opening Remarks

It is a great honor for me to offer my greetings to His Excellency Mr. Eduard Habsburg-Lothringen, ambassador of Hungary to the Holy See and the Sovereign Military Order of Malta, here in this thousand-year-old abbey. Perhaps it is more than a happy coincidence that we find ourselves in this sacred place dedicated to the protomartyr Saint Stephen. In fact, the first Christian king of Hungary, who lived between the late 10th and 11th centuries and would later be canonized, was baptized under the name of Stephen. With the Crown of Saint Stephen (which had been sent to him, according to tradition, by the Holy See), the primate, that is, the archbishop of Esztergom, had the right to crown the king of Hungary. Cardinal Mindszenty expressly wished to be the titular of the basilica Santo Stefano Rotondo in Rome.

Above all, Saint Stephen is the first of a long line of martyrs and confessors for the faith who, by the offering of their lives and the acceptance of persecution, manifested their fidelity to Jesus Christ, that same fidelity which drove Cardinal Mindszenty to endure the most severe physical and moral sufferings, inflicted on him by a brutal, totalitarian, and anti-Christian regime. Moreover, it was on the evening of the Feast of Saint Stephen, December 26, 1948, that he was arrested, right before the eyes of his elderly and heartbroken mother.

Cardinal Mindszenty’s name is not unknown in Genoa, not least because of the great veneration that our beloved Archbishop Giuseppe Cardinal Siri had for this confessor of the faith. In his Memoirs, Cardinal Mindszenty recalled that, upon arriving in Rome in 1971, “In St. Paul’s a priest joined me, seized my hand, kissed it, and thanked me for my sufferings for the Church. Finally he introduced himself: ‘I am Cardinal Siri.’”

We are here to continue this thanksgiving and veneration. In Genoa, a “Cardinal Mindszenty League” was established, which organized conferences and conventions in the years during which our country was on the verge of falling into the same totalitarian regime that persecuted Cardinal Mindszenty. I like to recall that at the invitation of the “League”, on June 2, 1980, Cardinal Siri held a solemn, scholarly commemoration of Cardinal Mindszenty in the Sala Quadrivium, and from this commemoration I will take out a few quotations.

- Biographical Notes of Mindszenty

The cardinal was born on March 29, 1892 in Mindszent to parents of distinguished status; his paternal surname was Pehm, but in protest against the Nazis, since his surname had Germanic origins, he changed it to Mindszenty in 1941, taking it from the name of his hometown. He was ordained a priest on June 12, 1915. Of his early years in the priesthood, he recalls: “I was especially happy when — even in cases of those who seemed to have hopelessly fallen out with God, the Church, and themselves — I was able to revive faith by persuasion and guidance.”

As early as 1919, he was arrested and imprisoned under the Karolyi regime and then under the far more terrible regime of Béla Kun. We do not have enough time to describe in detail the episodes of his first imprisonment: Suffice it to say that even then the strength of spirit of the servant of God emerged, combined with a great meekness and a certain irony. When a police officer came up to him after the Béla Kun uprising and said, “You are under arrest”, the young Don Jozsef Pehm (as he was then called), who was already in prison by order — as was said before — of Karolyi’s regime, wryly responded, as he reports in his Memoirs, “that I had been so since February 9, 1919, and asked what this outlay of governmental authority was all about,” and he thought to himself, “the dog was the same, but his collar was now redder.”

After the fall of the so-called dictatorship of the proletariat, in August 1919, he was appointed parish priest in Zalaegerszeg, where he remained for twenty-five years. Of this period, we can only mention here his great pastoral zeal, as a result of which he founded six more parishes, opened schools, created and presided over associations, and did not fail to devote himself to historical studies, with publications on ecclesiastical history, some of great value.

On March 25, 1944 he was consecrated bishop of Veszprém, but in the same year he was arrested and imprisoned for the second time, this time by the Nazis and their collaborators, members of the so-called “Arrow Cross” Party. Beyond the pretext that was used, the real reason for his arrest was that he had expressed his opposition to the deportation of Jews from Veszprém; this second imprisonment did not end until April 1945, with the end of the war. He noted in his Memoirs: “From the West the brown peril threatened us; and from the East, the red.”

On October 2, 1945 he was promoted to archbishop of Esztergom (Strigonia in Latin) by Pius XII, and then primate of Hungary. In his Memoirs, he recalls that this decision was taken personally by the pope, who, as he wrote: “knew my character, knew that I was more concerned with the care of souls than politics… The nuncio had fully informed the Holy Father about my administration of the diocese and also about my imprisonment.” Cardinal Mindszenty again writes about his relationship with Pius XII: “In December 1945, during my trip to Rome, I managed to open generous sources for Hungarian Caritas. The Holy Father Pius XII received me with indescribable kindness. When I told him about the difficult situation in Hungary, he opened the way for me in all directions where I could find help.”

For several pages of his Memoirs, Cardinal Mindszenty dwells on the figure of Pius XII, emphasizing the gentleness and goodness of this pontiff:

I had always esteemed Pius XII as a towering personality; now I was able to see for myself what a kindly Holy Father God had given us. He was thoroughly familiar with Hungary’s Church and the situation of Catholicism in our country. As papal legate to the Eucharistic Congress in 1938, he had come to Budapest and since that time had been warmly disposed towards us.

In the consistory of February 18, 1946, Mindszenty was appointed cardinal. He recalls:

It may be that my description, which gave him insight into our situation, prompted him to embrace me at the consistory and to say: “Éljen Magyarorszäg!” (“Long live Hungary!”) When he placed the cardinal’s hat on my head, he said in a deeply moved voice: “Among the thirty-two you will be the first to suffer the martyrdom whose symbol this red color is.”

On February 28, he received from the pope the archiepiscopal pallium, and on March 4 he had his last audience: They would never see each other again on this earth. Mindszenty writes:

That was my last meeting with Pius XII. But his paternal kindness and his sympathy continued to accompany me. He constantly intervened in my behalf whenever difficulties arose for me. At every juncture he denounced the machinations of the Communists and also those of the so-called ‘progressive Catholics.’ I remember with great gratitude how he intervened for me when I was imprisoned and brought to trial, and I remember likewise the loving words of the telegram he sent me after my liberation in 1956.

In short, Pius XII and Cardinal Mindszenty were bound by a profound mutual esteem that, as we have just mentioned and as we shall see better later on, would manifest itself especially in the terrible moment of the arrest and the mock-trial that the primate of Hungary had to endure.

Before taking those facts into consideration, however, we should clarify the function of the archbishop of Esztergom, and in this regard I give the word to Cardinal Siri, who, in his aforementioned commemoration, had explained:

The function of the archbishop of Esztergom is unique in history because, from St. Stephen onwards, he was considered prince of Hungary and therefore bore the name of prince primate of Hungary. This leads to the following consequence: When the king was absent from the country, the prince primate succeeded to the regency of the kingdom. Without this detail, which gave the primate of Strigonia a unique, absolutely unique, constitutional position of being the first after the king and replacing him in his absence, one would not understand the soul of this great man.

Not only that, but the Holy See had completed the work: It had given the archbishop of Esztergom the character of ‘Perpetual Papal Legate.’ Therefore — a unique case in the Catholic Church — only the primate of Hungary had jurisdiction over all the other bishops of the country. He was not simply a president of their national conference but was a superior and had jurisdiction.

It is necessary to remember this, — explained Cardinal Siri — because if one does not consider the constitutional function he had in the civil order, if his function as legate is not viewed as a very special representative of the Pope, and if one does not think of his knowledge of history that made him a participant in all of his people’s past anxieties and all their aspirations, one would not be able to understand Cardinal Mindszenty and would not understand that this man is as much a hero for the Church as he is a hero for his country.

We can, therefore, also better understand the significance of the illustrious presence this evening of His Excellency the ambassador of Hungary, a presence which recalls precisely this dual role of the figure of the prince primate, a role played with extraordinary dignity and courage by Cardinal Mindszenty.

- Third Arrest, Trial, and Imprisonment

We now enter into the heart of the drama experienced by Cardinal Mindszenty. Faced with the rise of the Communist regime, totalitarian and freedom-denying, beginning with freedom of education through the nationalization of the confessional schools (the conquest of the youth and the confessional school were the heart of the conflict between the Church and State), the prince primate of Hungary could not remain silent and not denounce, with the means that his position and the enormous prestige he enjoyed granted him, the blatant illegalities committed by the regime. In turn, the regime, according to the usual tactic of totalitarian systems, which combine violence and lies, first launched a campaign of defamation and delegitimization against the cardinal, culminating with his brutal arrest on the evening of December 26, 1948, as already mentioned.

Some object that Cardinal Mindszenty was not ‘malleable’, that he was unwilling to dialogue and compromise, but he well knew what the outcome would have been, in those conditions, knowing the history of the Orthodox Church in the Soviet Union, that is, not only the subjection of the Church to the State, but, if historical circumstances had not prevented it, the very destruction of the Church, as well as of every form of religion, according to what was the objective of atheistic communism, described by Pius XI in his encyclical Divini Redemptoris (1937) as “intrinsically perverse”. (para. 58) [The Latin “intrinsecus sit pravus” has been rendered in English as “intrinsically wrong”, but “pravus” may also (perhaps, more accurately) be translated as “perverse”, “vicious”, “bad”, etc. The Italian reads “intrinsecamente perverso”. -JD]

For this reason, Pius XI warned:

[N]o one who would save Christian civilization may collaborate with it in any undertaking whatsoever. Those who permit themselves to be deceived into lending their aid towards the triumph of Communism in their own country, will be the first to fall victims of their error. And the greater the antiquity and grandeur of the Christian civilization in the regions where Communism successfully penetrates, so much more devastating will be the hatred displayed by the godless. (Ibid.)

And the hatred of the “godless” manifested itself with virulence against Cardinal Mindszenty.

Once arrested, he was taken into Andrássy Street 60, which we might call the equivalent of Via Tasso in Rome, a place of unspeakable torture and torment for many. He only had with him a small image of Christ crowned with thorns, which bore the inscription: Devictus vincit (defeated but victorious). He remained in this building for thirty-nine days, during which, day and night, he was subjected to all sorts of physical and moral violence, mockery, humiliations, ferocious beatings, in order to get him to sign a pre-packaged document containing the ‘confession’ of the false crimes attributed to him.

When, drained by the physical and moral tortures, he could no longer resist, he used a clever scheme: He signed, but next to his signature he added two letters, C and F, which mean Coactus Feci (I was forced to do it). When his torturers asked him what those two letters meant, he replied that it was the abbreviation of Cardinalis Foraneus, a title that would distinguish provincial cardinals from those of the curia. For some time they believed this explanation, but then they found out about the trick and the tortures continued.

But what were the charges that were made against the cardinal? Basically three.

The first was that he would have conspired with Otto von Habsburg, son of the last Emperor Charles, to re-establish the monarchy:

In 1947, after the Marian Congress in Ottawa, I in fact received Otto von Habsburg, as can be seen from your own prepared statement. I did so at his, not my request, in Chicago… and then only for a half an hour audience. Your conjecture is correct that I spoke with about the predicament of the country and the problem of the Church.

Despite his explanation, however, his accusers still considered him guilty of conspiracy: It must be like this! He must have conspired! That must be so, it cannot be discussed, no contrary evidence can be admitted.

There is something ironic, tragically ironic, about the dialogue between the Cardinal and his torturers. They shouted at him, “Your business is to confess to what we want to hear”, to which he replied, “If facts don’t count here, if the minutes, the interrogation, and the charge are only pretense, untenable nonsense without any basis in fact, a confession shouldn’t be necessary either.” We can easily imagine what the reaction to his words was, the same reaction that the soldier had when he slapped Jesus for what He said to the high priest.

The second charge was of espionage. It was baseless as the one before, but, as we have seen, in that farce of interrogations with forced answers, and then in that trial with merely demonstrative function, the facts had no importance; all that mattered was what the regime wanted the charge to be.

The third accusation concerned currency trafficking. On this point, it should be explained that after the war, in a period of transition, the cardinal had sought, especially on the occasion of his trips to Canada and the United States (and thanks to the powerful apparatus of Cardinal Spellman), aid to feed the starving people, and he had indeed received it. In Budapest alone, he had opened 126 food distribution points to feed tens of thousands of people who, otherwise, would have starved to death. Now, because he introduced foreign currency to feed the people, he was accused precisely of currency trafficking.

The cardinal himself noted:

Our kitchens would have had to close forthwith if we had had no American or Swiss money at our disposal… If normal political conditions existed in Hungary today, the government would thank Hungarian Catholicism rather than practice torments and tortures here in Andrássy Street that future generations will feel ashamed of.

It is evident that these were only pretexts, which the regime used through a lightning trial that began on February 3, 1949 (and ended after only three days) to demolish its proudest and noblest opponent: Bela Kun had not succeeded, the Nazis had not succeeded, neither would the Communists. The outcome of that trial, in which the defendant’s counsel seemed primarily concerned with defending his accusers, could only be a conviction, and that was life imprisonment.

- Pius XII’s Defense

But before humanity and history, Cardinal Mindszenty had a very different defender than the one assigned to him by the regime during that tragic farce: The ‘Pastor Angelicus’, the great Pius XII, whom I like to call ‘the Pope of Charity’ and who had already, as we have seen, demonstrated at various times his esteem and affection for the primate and for Hungary. Unfortunately, in those moments, the servant of God could not receive the words that the Pope had dedicated to him. “What a consolation,” he recalls in his Memoirs, “it would have been to me in Andrássy Street and in Markó Street if I had heard about the pope’s loving concern. But not a gleam of his kind, bright words penetrated into the darkness in which I dwelt.”

According to some accounts, Cardinal Mindszenty would, however, receive the comfort of Padre Pio, who, in a phenomenon of bilocation, would visit him in prison, even bringing him bread and wine for the celebration of Holy Mass.

Back to Papa Pacelli [Pope Pacelli]: On January 2, 1949, Pius XII had sent a letter to the Hungarian episcopate in which he expressed his regret and strong protest against the grave insult inflicted on the entire Church through the arrest of the cardinal primate, whose high praise he weaved, which also deserves to be remembered for the perennial teaching it contains about the figure of the ‘Good Shepherd’ and his duties:

We are well aware of the merits of this excellent Pastor; we know the tenacity and purity of his faith, we know his apostolic strength in safeguarding the integrity of Christian doctrine and in vindicating the sacred rights of religion. That if, with a fearless and strong heart, he felt the duty to oppose when he saw the freedom of the Church was increasingly limited and in many ways coerced, and, above all, when he saw the ecclesiastical magisterium and ministry impeded to the grave detriment of the faithful — which must be exercised not only in the churches, but also in the open air in public manifestations of faith, and in schools and colleges, with the press, with pious pilgrimages to sanctuaries and with Catholic associations — this is certainly not a cause for accusation or dishonor for him, but rather of high praise, since it must be ascribed to his office as a vigilant pastor. (Letter “Acerrimo Moerore”, to Hungarian Archbishops and Bishops, January 2, 1949)

In short, the ‘Good Shepherd’, according to Pius XII, is a “vigilant shepherd”, who must know how to prove himself “fearless and strong” in defending the “sacred rights” of the Church and of religion, which are then the sacred rights of God over the souls redeemed with His blood.

He also admonished, to the comfort of the bishops and the faithful, “that the Christian religion may be slandered and fought against, but it cannot be defeated!” (Ibid.) as demonstrated, if I may say so, by this solemn commemoration: Cardinal Mindszenty was arrested, tortured, convicted, imprisoned, but he was not defeated (Devictus vincit).

Several articles were published in L’Osservatore Romano before and after the trial; on February 12, 1949, the excommunication latae sententiae was declared, reserved speciali modo to the Apostolic See, together with other severe canonical penalties, against those who, in any way, had collaborated in the arrest of the primate, his detention, and his conviction.

On February 14, 1949, Pius XII held an extraordinary consistory in which, before the Sacred College of Cardinals, he condemned the injustice committed, denouncing the abuses perpetrated, made manifest by a series of circumstances: “the excessive and suspicious rapidity of the procedure, the artificial and captious construction of the accusations, the physical condition of the Cardinal… which suddenly made of a hitherto exceptionally energetic man… a weak and vacillating-minded being.” (Address “In hoc Sacrum”, to the Sacred College of Cardinals during the Extraordinary Consistory, February 14, 1949) We must not forget that, alongside the physical tortures, and despite the great caution of the cardinal, some sort of drugs were added to his food. For the pope, only one thing was clear: “and that is that the main purpose of the whole trial was to unsettle the Catholic Church in Hungary”. (Ibid.)

On February 16, Pius XII left a hopeful note to the diplomatic corps, which had gathered to offer the solidarity of the civilized world to the pope’s grief over the arrest and conviction of Cardinal Mindszenty:

In the conflict that sets the defenders of a totalitarian regime against the champions of a conception of the state and society founded on the dignity and freedom of man, willed by God, this historic audience faithfully reflects the thought and aspirations of by far the largest and healthiest part of humanity. It manifests the reaction of the Christian and also simply human conscience against every oppression and every arbitrariness, against every denial of justice and every threat to rights and sacred principles, whose integrity is a necessary condition for the respect and safeguarding of inalienable fundamental values. (Address “Nous apprécions”, to the ambassador of Columbia and representatives of the Diplomatic Corps the Holy See, February 16, 1949)

I believe that we should not underestimate the lesson that still comes to us today from the unity then demonstrated by the ‘civilized world’, of which the august pontiff became the interpreter, in the face of the barbarity of totalitarianism. But Pius XII made his most splendid, masterly declaration in an address to the Roman people on February 20, 1949, to that Roman people who never failed to flock to the call of the one whom they felt to be, because they had experienced him as such, their father, pastor, and defender. It was a true masterpiece, not inferior to the speeches of the greatest orators of Ancient Rome: “The condemnation inflicted,” thus began the Pontiff, “amidst the unanimous disapproval of the civilized world, on the banks of the Danube, on an eminent Cardinal of the Holy Roman Church, has aroused on the banks of the Tiber a cry of indignation worthy of the City.” (Address “Ancora una volta”, to the Faithful of Rome, February 20, 1949) We no longer have the time to dwell on this extraordinary address, but we cannot fail to recall at least that pressing dialogue with the crowd:

Now, it is well known what the totalitarian and anti-religious State requires and expects from her [the Church] as the price for her tolerance and her problematic recognition. That is, it would desire:

a Church that remains silent, when she should speak out;

a Church that weakens the law of God, adapting it to the taste of human desires, when she should loudly proclaim and defend it;

a Church that detaches herself from the unwavering foundation upon which Christ built her, in order to repose comfortably on the shifting sands of the opinions of the day, or to give herself up to the passing current;

a Church that does not withstand the oppression of conscience and does not protect the legitimate rights and the just liberties of the people;

a Church that with indecorous servility remains enclosed within the four walls of the temple, forgetting the divine mandate received from Christ: Go forth to the crossroads (Math. 22:9); teach all peoples (Math. 28:19).

Beloved sons and daughters! Spiritual heirs of an innumerable legion of confessors and martyrs!

Is this the Church that you venerate and love? Would you recognize in such a Church the features of your Mother’s face? Can you imagine a successor of the first Peter submitting to such demands?

The Pope has the divine promises; even in his human weakness, he is invincible and unshakable; he is the messenger of truth and justice, the principle of the unity of the Church, his voice denounces errors, idolatries, superstitions, condemns iniquity, makes charity and virtue loved. (Ibid.)

Through the impassioned defense of Cardinal Mindszenty, Papa Pacelli asserted the supernatural greatness of the Church, the eternal promises it enjoys, the inalienability of its rights and duties, which outline its irreformable profile, resistant to the passage of time and fashions, because it adheres to the image given to it by the Divine Founder.

- Conclusion

The subsequent events are well known: The years of imprisonment, which gradually eased over time; the triumphant liberation in 1956, which saw demonstrations of joy not only by Catholics but also by Protestants, in short, by all the Hungarian people who had not forgotten their prince primate; the famous radio message to the country on November 3, 1956; the Soviet occupation; the escape to the American embassy, where Cardinal Mindszenty stayed for fifteen years until 1971. On September 28 that year, he arrived in Rome and, among his first acts, celebrated a Mass of Thanksgiving at the tomb of Pius XII (cf. Memoirs).

In the following years, he settled in Vienna and from there began traveling the world, to visit and comfort the Hungarians in the diaspora until his death in Vienna on May 6, 1975. Fifteen years later, his remains were transferred to the Cathedral of Esztergom. In 1994, the cause for his beatification commenced, which is now in its Roman phase. The Mindszenty Foundation [in Hungary], whose president is the father of H.E. the ambassador and of which the ambassador himself is a member, has promoted and supported this cause.

From a procedural point of view, it is worth mentioning that already in May 1990, the nullity of the mock trial that Cardinal Mindszenty was forced to undergo was declared, and in 2012 his full legal rehabilitation was achieved. It must be remembered, however, that in November 1973 he had ceased to be archbishop of Esztergom, and therefore primate of Hungary, not by his own will but by order of the Holy See. Nevertheless, during his lifetime, no successor was appointed. In this regard, it seems useless to dwell on the controversy, which concerns the remnants of history.

Let us rather ask ourselves: What remains of this whole affair? There remains the example of an intrepid shepherd, who did not fear sacrificing himself for the Church and the Fatherland through a continuous sacrifice, which, albeit in diverse forms, lasted for years. There remain the words of a holy pope, who wore the tiara like a crown of thorns, which tormented him not only during the Second World War but also during the post-war years, no less dramatic for his heart as universal father. Finally, there remains the invitation to hope, so strongly recommended by Pius XII, because hope is founded on the divine promises, the hope, which is certainty, that the most violent storms will not be able to submerge the Church of Christ.

Hence, this evening, let us offer our praise and thanksgiving to the Lord of history.

Emilio Artiglieri, attorney

President, Comitato Papa Pacelli – Associazione Pio XII

[Orignail Italian: https://ungheriasantasede.blogspot.com/2017/06/pio-xii-e-il-card-mindszenty-celebrati.html]