Things are surreal, and getting more so by the minute – or so it goes. In the first minute or so of his interview with Elon Musk, Donald Trump describes the recent attempt to assassinate him as ‘surreal’ multiple times. It’s used to describe wars, and rumours of wars; the state of the Church, and the behaviour of some of her more erratic members. But it’s also used to describe great feats of musicianship, athleticism.

What’s real, and what’s surreal?

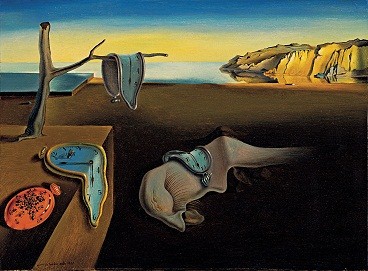

I was surprised to learn that the term is of rather recent origin, its first use dating back to 1937, derived from the earlier self-described ‘surrealist’ movement in art. Salvador Dali’s ‘limp watch’ from his 1931 work ‘The Persistence of Memory‘ became an iconic symbol of the surreal.

One definition has it that what is surreal is marked by the intense irrational reality of a dream.

‘Intense irrational reality’. Hmm. It’s irrational but seems real.

Like any number of other words, surreal evolved to mean almost its opposite: From that which seems unreal, and is so, to that which seems unreal, but is all too real, whether in a bad or good sense. Being in a plane falling out the sky is surreal, but so is falling in love, especially for the first time (which should, ideally, be the only time).

Movies are almost by definition surreal: They have to exaggerate reality to keep viewers’ attention. Flannery O’Connor’s stories were surreal, since, as she said, people were too morally deaf to hear anything else, and she had to write in capital letters . All literature and art has to have some surreal quality, to re-present reality in a way that we have not seen it before. As Chesterton quipped, only a child would not be bored by a realistic novel. For such children, all reality is surreal – they are filled with awe at a blue sky, or a waving flower. Aristotle and Aquinas declared that poets and philosophers are filled with wonder – mira – for the world is a wonder-ful place, as a song some time ago sang. Would that we blasé adults might become like such little children, to see the world as God always sees it, for the first time.

But to get to that state, we have to be grounded in reality, which is, what is really real, not on the un-reality – the fake surreality – of technology. Unlike past ages, when life and art were distinct and we knew which was which, they now coalesce, mediated by the ubiquitous screens. With the exponential advance of AI-deep fakes – something Gavin Newsom has just made illegal in the state of California, and bonnes chances with that – it’s more and more difficult to tell what is real, from what is sort of real, from what is completely – or nearly so – unreal. Everything is now surreal, a Dali-esque dreamscape, or nightmare, depending on your point of view.

Even if what is portrayed on screen is ‘real’, those who control that technology only reveal to us what they want us to see, like the woman of Billy Joel’s eponymous song. Edited, filtered, censored and massaged. Chesterton warned in his own far less technological day that newspapers were like giant spotlights, illuminating one moment, and leaving the rest – and the rest of us – in the dark. Wars and rumours of wars, indeed.

Saint Thomas defines truth as adequatio rei et intellectus – a conformity between the mind and reality. If our minds become unhinged from what is real, we cannot, therefore, find truth. We are all now in Plato’s cave, watching images of images – but the images now seem more real than reality.

We need to anchor our minds, our very selves, in reality – in what is truly real, if you may pardon the redundancy. This means first and foremost what is right around us, that is, local life, which, like the present day, has enough evil to suffice. And we may add, enough good, even more than enough. Live life, and life will be given you. For only what is really real and truly true – however surreal it seem – will lead us to sanity, to charity and to heaven, the realest and surreal-est of all.