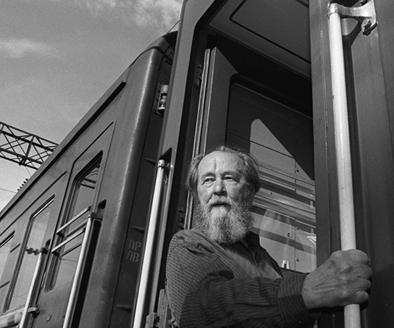

I just finished reading Joseph Pearce’s biography of Alexander Solzhenitsyn, subtitled ‘A Soul in Exile’, a remarkable book, packing a very full life into a very readable pages, showing what the indomitable will of one man can do against a vast totalitarian regime. Solzhenitsyn’s life is almost a reverse 1984, and he the anti-Winston. Orwell’s anti-hero – or, more properly, non-hero – as we know (spoiler alert!) caves in the end, becoming a pliant tool of the state, even condemning his own lover.

Solzhenitsyn never did give in, steadfast and stalwart. As the saying goes, he spoke truth to power, and lived and vivified it more than that tired slogan it has become. (See his essay ‘Live Not By Lies’, a brief manual on how one individual can, and should, change a culture mired in falsehood. Those are tough words by which to live – but how necessary they be. And they are becoming ever more so).

True, he was an atheist and a Marxist until well into his early adulthood, and it was only his suffering in the decade he spent in the Gulag that converted him back to his childhood Faith – his mother had always been devout, and planted the seeds in her son. From that time to his death, Alexander never again wavered, but rather, by the grace of God, grew from strength to strength. His marriage to his first wife, who clung to her Marxist-atheist delusions, fell apart soon after their reunion. He remarried (the first marriage was outside the Church and, hence, not valid), and this union, bonded by the grace of the sacrament, proved fruitful and lasting – three sons were born. Solzhenitsyn and his family were exiled from his native land, raised his children in a secluded property in Vermont, only to return in triumph in his later years (he was in his later seventies), and died on Russian soil.

Triumph of a sort. For Solzhenitsyn saw that with the fall of Communism – at least as it was instantiated under Stalin – a more insidious evil arose from its corpse, an enervating hedonism and materialism, a care for this world only, the loss of the transcendent and the concomitant culture of death. In his homeland, the great man was often mocked and derided by the hip and cool younger generation as relic of a bygone era of superstition and the stricture of the old religion.

But Solzhenitsyn soldiered on, knowing that it was only Christ and His ‘old religion’ – which is always new and young and life-giving – that could save us and our civilization, with his prodigious and unflagging energy he continued writing, speaking and traveling across Russia and even the world, right up to the end. He died, as he had hoped, in his native land he loved so much, on August 3rd, 2008 at the age of 89.

A final word: Pearce’s book has an epilogue of S’s prose poetry, and I was struck by a perceptive line the one on ‘Growing Old’, which puts into perspective the cult of youth that so obsesses our society – hand in hand with the hedonism that is rotting us from within. As he puts it, ageing is “not a downhill path, but an ascent”. And earlier in the brief poem: “How much easier it is then, and how much more receptive we are to death, when advancing years guide us softly to our end. Ageing thus is in no sense a punishment from on high, but brings its own blessings and a warmth and colour all its own”.

I may quibble that death – and its prelude of getting old – is an effect of that original sin of Adam. But S. is right, that God brings far greater good out of that suffering – for the end of this life is but the beginning of a far, far better one, the end of our true exile, where, as Leo XIII put it, we will truly begin to live.