Appeals for freedom, justice and mercy are commonplace. All seems right. We impulsively acknowledge and defend them undisputedly. But, in the spirit of modern revisionism these core principles have been stealthily expropriated and deceptively portrayed How is this happening?

We answer the call-out for democracy, social cohesion and even planetary salvation as if to a familiar voice. But all familiarity is situated within its historical context, and ours begs discernment. If one should inquire for what or whom is the cry for justice we may have to contend with a reply absent prepositions; laden with platitudes, resentful of the truth and cynical to the protests of reason. Since the recent addition of the qualifier, “social” before the word justice, we have been softly conditioned to spin our judgments around a helix of victim fixations, including a few of the most current: BLM, ESG, SEL, DEI, MAiD, and their forerunner, LGBTQ which, despite whopping contradictions, owes their bias to the Christian model with its standard concern for victims and, before we forget entirely – justice, mercy and freedom.

The last century marks a turn through modern western history widening the way to a devil-may-care free-for-all, openly contemptuous of moral structure which is all the more perplexing given the expense of energy and passion on the ever-so-urgent and ever-so-virtuous roll-out of corporate-sponsored social justice agendas and their respective crusades.

It is difficult to convey the way things are at present. Western societies are riddled with grievances that rally attention and generate confusion at the same time. We negate what we claim to affirm and affirm what we claim to negate with artfully positioned complications and occlusions – you may say, demonic occlusions, which are steadily winding through the core depth of our cultural machinery and therefore – it is wise to proceed prayerfully.

Though it seems contradictory, even atheists who are uncomfortable with overt religious pieties are culturally at home with the classic messages of Judeo-Christian principles of justice, mercy; freedom and charity, as these have woven the social fabric throughout the generations. The Christian concern for victims, when it has not been personally imbued, can still be deeply imbibed even if diminished to a thin aura of what it had traditionally represented. It is absurd that the Christian concern for victims has also transmogrified into a selling point for the politics of libertarian lobbyists where even the churchgoing will make concessions to the most unseemly mockeries of Christian doctrine. Provided they are peddled as compassionate and arrayed under a love-thy-neighbour gloss we likely lose sight of the verbal trickery that has just made bedmates of Marxist “woke” ideology and Abrahamic spiritual values.

That the contents of sacred authorship have been culled for the implicit purpose of sabotaging their intended meaning cannot be accidental, for we have been habituated to accept the inversion of our deeply held moral values through a duplicitous use of words, and seemingly righteous social campaigns. All seems right. This is why, in an environment of socially incongruous mores, it is as unwise to assume a moral contingency in a political context as to justify a political action in terms of its moral contingency.

The mood of the day venerates novelty and peculiarity as destabilizing forces. Our docile acquiescence to ‘queerness’, for example, marks the condition of a destabilized faith and a permissive nod to a new and de-sacralized religion, but a religion nonetheless. The modernist “woke” cult claims open-armed neutrality, generosity and perfect equality, yet it is Marxism’s latest disguise – a blend of gnostic heresy and communism appearing under a raffish battle-cry of shibboleths and sneakily arrayed acronyms used to strongarm a political angle with symbolic moral affirmation. By the wiles of a long and insidious design we have come to submit to tone and feeling over content and substance and, as we do, we slide into an imitation, a parody of our cultural heritage. We are acquiescing to a false religion that mimics our deeply held values to the degree that it brashly dismisses their very essence.

Because these obscurant strategies are at play, it is on us to reconstitute the presence of our foundation as a culture and quit frolicking between worlds. Our world has deep roots. The fantasy of the modern woke cult is on borrowed time. If all the esoteric horse-play were really about virtue and charity, and not an effort to subvert and propagandize, their proponents would brace the history of the desert-wandering Hebrews who became the first to expound ethics in synchronicity with a covenantal purpose. The providential path leading from Abraham to Moses onward would signal their legacy. But wokeism, in its rigid condemnation of biblical relevance, is pacing its way to obliterating sacred text – that is, once it has finished reappropriating its contents.

Yet, it is our biblical legacy, even in its philistinized modern context, that claims a sentient hold on our culture, or more specifically, on the emotional vestiges of our cultural psyche. For, as much as modern society reinstitutes the cruel ritualistic practices of a pre-Mosaic world, it is unlikely to reject its dependency on the drama of Exodus for its moralistic high ground. Rather, the trenchancy of the biblical vocabulary and its moral tone is in use today in full unabashed pastiche; our cancel culture and its sermonic platitudes – padded in esoteric sweet-talk. All we have done is transferred the grammar of a deeply ingrained moral language onto a neo-pagan worldview – omitting its beauty, and vivifying meaning.

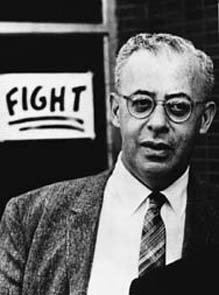

Among the multitude of players in the second half of the last century who helped shape this worldview in its social context was the artful Saul Alinsky, who stands out for his creative, yet shrewd handling of public perception. Superficially, Alinsky projected the persona of a sharp advocate for social justice, for the poor and down-trodden; an arch-defender of the “have-nots” against common bureaucratic abuses but on closer examination he was a cunning tactician – a genius in the art of shaping public opinion to a socialist party line.

Born in Chicago,1909, Alinsky was by training a criminologist, chiefly talented as a community organizer. But most importantly, though a little-known figure today, he was one of the foremost American-born infiltrators of the Catholic Church in the twentieth century.

On the extreme opposite end of the spectrum was Servant of God Dorothy Day, a contemporary of Alinsky, devout convert to Catholicism, supportive of the Church’s controversial sexual mores, defender of private property, deeply orthodox in her devotions and tireless worker on behalf of the poor. We know of Day’s integrity, from her prolific journalistic writings (The Catholic Worker, Commonweal, and several autobiographical books) where she expands on the dear cost of her continued activism which compelled her into the public sphere, but more so – incalculably more so – into intimate daily contact with people suffering the misery of poverty.

Day held a passing admiration for Alinsky as they both envisioned a radical transformation within the abject fringes of society, intent on building from the ground up rather than from the top down. Nevertheless, she chose to keep Alinsky at a distance, as her Christ-inspired service was irreconcilable with Alinsky’s Machiavellian-inspired approach.

Unsurprisingly, Alinsky was never able to subvert Dorothy’s pure heart. Where Day was led by her Christian perception of reality, Alinsky distorted reality in order to lead public perception to his own staged version of it. Where Day would offer immediate consolation to the needy in the order of the Beatitudes, he would strategize to incite rebellion in the order of Simon the Sorcerer (Acts 8:9-20). Alinsky was Marxist in his leanings, Nietzschean by temperament and Houdini-like in his schematics; a virtuoso in the magic of mind-shaping.

It is not hard to see why early copies of his 1971 book, Rules for Radicals, were dedicated to Lucifer. Was Alinsky being characteristically provocative? Or was he playing to the rebellious instincts of a malformed and immature audience and setting them up to be useful agitators to a broader public? Alinsky’s distinguishing Machiavellian trademark is a how to in mimetic reversal; not how to keep the prince in power but how to confiscate power and reimagine the principality. His “visionary” instinct played into the “ground-up” mythology of Babel for its exclusive reliance on human activity and worldly organization to garner power: “The Lord came down to look at the city and the tower that man had built “, reads Genesis (11:5). Alinsky intentionally circumvented the obvious irony of this story.

A common criticism of his Pragmatic Primer for Realistic Radicals (the sub-title) is that it conforms to the idea that the end justifies the means. Alinsky denied this charge, but the book clearly commends the use of confusion, deception, ridicule, threat and polarization; an “our people” against the “enemy” stratagem. In keeping with his own philosophies, he would willingly lend his expertise to the political left, whereby the political theatre would be staged accordingly. To offer an example, consider number ten in the subset of rules where he states: “You do what you can with what you have and clothe it in ethical garments.“ Dinesh D’Souza offers a case in point: Alinsky was once approached by a group of student activists preparing to disrupt a republican rally with signs reading: GOP=KKK. Well aware that the Ku Klux Klan is the brainchild of the American democratic party, he advised against the outright lie in exchange for a simple obfuscation; a ruse more psychologically savvy than the one they had originally planned. They should dress, Alinsky recommended, in white Klan-style robes, and gesticulate flauntingly in support of the republican message. In other words – smudge your opponent.

The years surrounding the book’s publication were the operative days of the Black Panthers and Weather Underground, two American organizations notorious for home-grown violent leftist activism. Always on the side of the underdogs he leaned in favour of their cause but not without disapproval. It would appear that he stood opposed to their criminal behaviour – their incitement of terror. But that concern was secondary. His most pressing objection was their tactical naivety. The violent thrust of these groups was simply the less advantageous route to rebellion. It kept them much too vulnerable to public scrutiny, and therefore, endangered the progression of their own revolutionary ideals. Overt tactics were the stumbling block in what Antonio Gramsci famously coined, “the long march through the institutions”, for which Alinsky was a distinguished contributor.

One can see how Alinsky strikes a chord with someone who has earnest sympathies for the poor, those with an anarchist streak and leery of institutional authority, but Alinsky was more like the Al Capone of good will. With a shrewd talent for divisiveness, he compacted all social complexities to an over-simplified disparity between (in Chicago street-talk) the haves and the have-nots. In the world, he said, “the have-nots lack money; in hell they lack virtue.” Alinsky identified with the have-nots and figured that he would prefer hell, as hell would situate him among “my kind of people”… “they have grievances to work out.” It should be noted that his use of “haves” and “have-nots” is an Alinskyan spin on the Marxian, and thereby, Hegelian dialectic of oppressed vs oppressor, which is, once again, the modern overwrought obsession with victimization – exploited for a perpetual table-turning victim saga. (It is imperative to the socialist creed that the victim idea is magnified and exploited as a phase of a much larger project where the tables turn, and keep turning until the victim declares himself the ultimate and glorious victimizer. Of course, the endgame is impossible considering it demands the annihilation of everything in existence!)

Though determinedly disengaged from his Jewish roots, he is unable to release that binding pull obligating the righteous to tzedakah (Hebrew for charity). But in Alinsky’s terms, charity is firmly situated in the strata of the finite, material world – confirmed, conformed and confined to an inversion of righteousness guided by a socialist creed. Not in the Judaic spirit, but under the spell of worldliness he formed the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF), The Back of the Yards Neighbourhood Council (BYNC) and in 1969, another by-product of Saul Alinsky, The Catholic Campaign for Human Development (CCHD), still fully operational today.

And this is where the hearts of the faithful will break. To identify the sordid charism of a Saul Alinsky mentality we need only reflect on one terse oxymoronic comment: “I will organize hell.” So stated, this was his desire – to outdo both God and the devil by banking on the native charity of the faithful. In collusion with and under the hermetic protection of several wolfish clerics going about in sheep’s clothes, he was able to pass off the corporal works of mercy as a negotiating tool for a secular humanist design scheme. If Dante were alive today, it would be interesting to see in which ring of hell he might have placed Bishop Bernard Sheil, Monsignor Jack Egan and Archbishop Joseph Bernardin for their active participation in the adaption of liberation theology for the modern North American church especially considering its deforming consequences in hindsight.

As for Dorothy Day, all this secular humanist activity was repellant; the abasement of the eternal for the ascendency of the temporal – anathema. She recognized the futility of the ouroboric mythologies of the world playing themselves out in the revolutionary mindset. Day reminds us, as she reflected on “the scandal of businesslike priests,” about the warnings of Christ, “The worst enemies would be those of our own household.” While Alinsky was preoccupied with effecting a deconstruction of society through any serviceable means at his disposal, and certain insidious clergymen were absorbed with deconstructing Catholic doctrine, Dorothy Day remained resolute in her deep love of the wounded Christ and of His mystical body – the Church, and by obvious extension, love of neighbour.

While the ground for Alinsky meant infiltration at the grassroots level, the groundwork for Day was realized in her submission to Truth as a Person; part of a trinitarian precept indivisible from The Way and The Life. Truth, for Day, was the formative cause and the defining spirit of her way of life. So, unlike Alinsky, Dorothy Day’s grassroot efforts required her to humbly follow where His feet did tread. Her conviction was clear. This is what it means to be radical: “Don’t worry about being effective. Just concentrate on being faithful to the Truth.”

Let us pray that Dorothy is raised to the glory of the altars.