Introduction

In 1973 the controversial Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade legalized abortion in the United States. In that first year alone, about 700,000 abortions were performed in the country and over 60 million have been performed through 2018. About one in four women will have an abortion by age 45.[1]

Since its legalization, abortion has been a divisive issue. There are three groups, each with differing opinions on the subject. Among registered voters, slightly over half of the populace believes abortion should be legal with some restrictions. The remaining two groups are about evenly divided between those that believe abortion should be legal under all circumstances and those that believe it should be illegal under all circumstances.[2]

Recently, several states have passed legislation which is considered extreme by many depending on their underlying views on the question of abortion. In 2019 the legislatures of New York[3] and Virginia[4] passed laws essentially allowing abortion up until the moment of natural birth. Public comments by the governor of Virginia seemed to allude to how this could lead to infanticide: “If a mother is in labor, I can tell you exactly what would happen, the infant would be delivered. The infant would be kept comfortable. The infant would be resuscitated if that’s what the mother and the family desired, and then a discussion would ensue between the physicians and the mother.”[5] Conversely, in the same year, the legislature of Alabama passed into law a bill banning abortion under all circumstances.[6] The state of Ohio passed legislation banning abortion at the time a fetal heartbeat is detected.[7]

As related to the topic of this paper, the consensus seems to be that the Alabama bill was passed with such absolute restrictions in order to force a review by the Supreme Court. The hope was that advancements in the science of embryology since Roe v. Wade will support the view that human life begins at conception. Tantamount to human life, the concept of personhood is being increasingly discussed within the abortion debate. If this argument is accepted by the court, it could dramatically impact the availability and practice of legal abortion in the U.S.

There seems to be a consensus building that personhood and when human life begins must be a critical issue involving the practice of abortion. Personhood can be viewed and defined in many ways: culturally, religiously, medically/scientifically. It is the purpose of this paper to review the concept of personhood primarily within the Catholic tradition.

Personhood: A Historical Review

There exists within the Catholic tradition a long history of thought relating to personhood as it applies to embryonic and fetal life. Much of this work was developed in the past and continues to evolve in the present in response to the issues of abortion and reproduction. Being biological issues, the discussion has centered about the question of when human life begins in relation to conception.

A tenet of traditional Catholic teaching has been that it is the presence of the soul that confers human status.[8] The origins of this view can be traced to the theory of Creationism, which held that the soul was created at some moment ex nihilo and then infused by God into the developing embryo.[9]

Pythagorean philosophy, which strongly influenced Plato, held the view that the soul existed on its own and was infused at the time of conception. The Stoics, on the other hand, held that the soul was infused at the time of birth.[10] Thus, within the context of the soul being the animating force of the body, there existed from very early on the concept of immediate animation versus delayed animation. This terminology can be misleading in that it could be implied that those who hold to a theory of delayed animation would doubt the early embryo to be “alive.” This is not the case. It is universally accepted that the early embryo is a living thing. For this reason, some authors have suggested the term early hominization and delayed hominization be used to more accurately relate to the presence of a human person.[11] Within the context of this paper, both “animation” and “hominization” shall be used interchangeably; they shall both be taken to refer to the presence of human personhood.

Plato (ca. 428-347 BC), as one trained in mathematics, dealt with abstract realities and timeless truths. He regarded the human person as essentially a soul that happens to be temporarily conjoined to a human body. This union serves to handicap the person in the pursuit of genuine knowledge in that bodily passions and impressions continually incline us to mistake temporary phenomena for eternal reality. Nothing worth knowing, in Plato’s view, is knowable through the bodily senses, for these have access only to the temporal order; knowledge of that which endures can only be attained by that which is itself capable of enduring—the incorruptible soul. Such knowledge is attained through immediate (non-mediated) recollection of, or direct acquaintance with, eternal reality. It was Augustine, some 700 years later, who is credited with having Christianized this Platonic view, substituting divine inspiration for Plato’s notion of recollection.[12]

Aristotle (384-322 BC), by contrast, with his background in biology and medicine, was led to very different conclusions on these matters. He accepted that there were eternal realities, but also temporal realities. He accepted that the eternal transcended the temporal; they were, in some sense, higher-order realities; but he did not accept that only the eternal was genuinely real. For Aristotle, the individual person is not essentially a soul, but a union of body and soul. From this Platonist and Aristotelian philosophy there emerges a distinct duality that continues until today to shape the discussion of the body-soul relationship.

Traditional Jewish thought on the beginnings of personhood was also creationist. Ancient Hebrews held that intra-uterine life did not become fully human until the “breath of life” was infused at birth.[13] As stated in Genesis, “The Lord God formed man out of the clay of the ground and blew into his nostrils the breath of life, and so man became a living being” (Gen. 2:7).[14] The human person was seen as a product of the relationship between the “clay of the earth” and the “breath of life”. Thus, “clay of the ground” referred to the material body, while “breath of life” corresponded to the spiritual soul. This biblical image was interpreted to indicate a hierarchical relation between the two: it is the soul that animates the material body. Only the fetus that had come out “into the air of the world” could be considered a person with a soul.[15] This view of the personhood of the embryo-fetus is further demonstrated in Exodus: “When men have a fight and hurt a pregnant woman so that she suffers a miscarriage, but no further injury (to her), the guilty one shall be fined as much as the woman’s husband demands of him, and he shall pay in the presence of the judges. But if injury ensues (to her), you shall give life for life” (Exod. 21:22-23). This text later underwent some refinement at the hands of the Hellenistic Jewish translators of the Septuagint. They introduced a distinction between the formed and the unformed fetus in the womb and condemned as a murderer the man responsible for even an accidental abortion of a formed fetus: “If … her child comes forth while it is not yet formed, then the penalty shall be a money payment …; but if it was formed, then thou shalt give a life for a life.”[16]

Drawing from this scriptural tradition, the earliest Christian communities held to the view of personhood being constituted by two separate realities. Within the framework of the classically derived philosophy of the time, these were extrapolated to the notion of body and soul.[17] True to its roots in Greek thought, this concept furthered the notion of a body-soul dualism. Origen (ca. 185-254 AD) fostered this dualism when he speculated that Adam was originally created as a disembodied soul who was subsequently, because of his disobedience, punished by a “fall” into a body.[18]

It was Gregory of Nyssa (ca. 335-395 AD) who, up to his time, offered the fullest consideration of personhood in defining the relationship between body and soul. He argued that man’s being is one, consisting of body and soul. As such, the beginning of his existence must be one as well. Thus, body and soul are created at the same moment on the occasion of generation. In contrast to the position of some Platonists and Origenists that souls were pre-existent, Gregory held that the soul is created along with the body and grows together with the body from the moment of its conception.[19] It is curious that the Greek Fathers, in spite of their philosophical heritage, generally embraced the notion that the human soul was present from the moment of conception.[20] Of major significance is that this view of the body-soul relationship moves away from the distinct duality of the past and engenders a more holistic notion of personhood. This understanding of what a person is found an important expression in the definition given by Boethius (477-524): “A person is an individual substance of a rational nature.” Over 700 years later, this view was further interpreted by Thomas Aquinas: “the individual substance signifies the subsisting singular that exists through itself and in itself, according to an irreducible mode, as a complete whole, a “hypostasis” that exercises the act of existing on its own account.[21]

The Latin Fathers, in contrast, continued on a line of reasoning that viewed ensoulment as a creative intervention of God in response to the conception caused by the parents. In effect, the product of conception became a person only after it was animated by God’s creation and subsequent infusion of the soul. Animation did not coincide with conception; it occurred when the embryo was ready for it.[22] This theory of delayed animation was espoused by Augustine (354-430) and remained the norm through the time of Anselm (1033-1109), who wrote that it is inadmissible that the infant should receive a rational soul from the moment of conception. This would imply that every time an embryo perishes soon after conception, a human soul would be damned forever, since it cannot be reconciled with Christ in the usual way through sacramental baptism.[23]

Gratian, in his canonical collection, the Decretum (ca. 1140), continued in the tradition of dualism and asserted that the soul is not infused until the fetus is formed. This set the precedent in canon law that eventually persisted until 1869.

Thomas Aquinas (ca. 1225-1274), with his Aristotelian leanings, embarked on a body-soul theory that was considerably more complex than those previously developed. For both Aristotle and Aquinas, the essence of all substances in the natural world was that they existed in a form-matter composite. This is what became known as the hylomorphic (literally: “matter-form”) theory of substances. The union of matter and form is not a contingent union, and no material can exist without some form. This means that the essence of a human person can no longer be thought of as an immaterial soul in temporary union with a material body. The essence of a person has to be thought of as an embodied soul. The embodiment of a soul is natural, that is, the soul is by nature embodied, and without this the human person would not have an individual soul. This means that there would not exist an individual human person. Therefore, the dualistic conception of the body-soul union was firmly rejected by Aquinas.[24]

The major weakness encountered in Aquinas’ view of the personhood of the embryo-fetus is a result of the limitations of science during that time period. Other than the knowledge of the existence of the male semen, there was little else known about the biology of reproduction; there was no knowledge of the existence of the female egg. His theory held that in the female “matter” there exists a “nutritive soul,” while the male semen was the carrier of the “sensitive soul.” At coition the female matter “is transmuted by the power which is in the semen of the male” and “is actually informed by the sensitive soul.” Later, at “quickening,” the “rational soul” was created and infused.[25] While weak in science, the philosophy of Aquinas is sound and his theory has been instrumental in moving away from the dualism that had its origin in Platonic thought.

The hylomorphic theory also, received the support of the Church at the Council of Vienne (1311-1312). The Council, while mediating a dispute within the Franciscan community, had occasion to address the question of the soul and its relation to human personhood. The statement of the Council “did not intend to explain the way in which the body and soul are united; it wished only to reaffirm that they were united.”[26] Every theory that maintains the substantial unity of the human composite is compatible with the statement of the Council. While the Council may not have defined the hylomorphic theory of human nature, it certainly endorsed it by stating that “the rational soul is the form of the human body.” In doing so, the theory has been for many centuries, until quite recently, the most widely accepted theory of human nature among Catholic philosophers and theologians. In spite of its worth in supporting a unified view of human nature, one of its implications has been the persistence of an ongoing theory of delayed hominization.[27]

Several editions of the Catechism of the Council of Trent, first published in 1566, clearly teach delayed hominization in connection with the mystery of the Incarnation:

But something that goes beyond the order of nature and beyond human intelligence is the fact that, as soon as the Blessed Virgin gave her consent to the Angel’s words … at once the most holy body of Christ was formed and a rational soul was joined to it …. Nobody can doubt that this was something new and an admirable work of the Holy Spirit, since, in the natural order, no body can be informed by a human soul except after the prescribed space of time.[28]

At the same time, in 1588 Pope Sixtus V, in his Bull Effraenatam, threatened excommunication to any who brought about “an abortion, or the expulsion of an immature fetus, whether animated or not animated, whether formed or not formed.”[29] The crime of abortion was thus considered grave in spite of a continuing differentiation between an embryo that is formed (animated) as opposed to unformed (not animated).

Pope Gregory XIV felt that the eternal damnation of those unwilling to petition for absolution was too severe a penalty. In his Bull Sedes apostolica (1591), he stated that “where no homicide or no animated fetus is involved, (one is) not to punish more strictly than the sacred canons or civil legislation does.”[30]

Prominent theologians[31] who have continued to favor the theory of delayed hominization have included Alphonsus Liguori (1696-1787). One of the Church’s leading moral theologians, he warned that “not every lump of flesh should be baptized which lacks every arrangement of organs, since it is universally accepted that the soul is not infused into the body before the latter is formed; in which case it can only be baptized if it shows some kind of vital movement, as prescribed by the Roman Ritual.”[32] He further stated, “On the other hand, some are mistaken who say that the fetus is ensouled from the first moment of its conception, since the fetus is certainly not animated before it is formed….”[33]

In spite of the apparently strong support for Aquinas’ hylomorphic theory and, by implication, the concept of delayed hominization, there were several factors that brought about increasing support for a theory of early animation (hominization).

One of the factors at play was faulty and imprecise science that led to erroneous conclusions. During the seventeenth century, optics and microscopes were quite rudimentary. The developing structures of an early embryo were often interpreted as being fully formed but very small. As a consequence, based largely on the work of Nicolaas Hartsoeker (1656-1725), there developed the commonly accepted theory of preformation.[34] According to this theory, the whole human being was contained as a homunculus[35] within the egg or sperm. An embryo did not develop so much as it grew. If there existed a well-developed body from so early on, it was only reasonable to assume that it was also animated by a soul from very early on.

A second factor involved in the move toward the theory of early animation was the influence of Cartesian philosophy. For Descartes (1596-1650), the soul is a complete substance in itself, as is the body. The soul is a thinking substance, the body an extended one. Within such a philosophical framework, immediate animation is quite acceptable. A human soul may be joined to a partially formed human body. Matter does not have to be highly organized before it is united to a thinking substance. While this theory has had its supporters, it seriously endangers theories of the unity of the human person and leads to great philosophical difficulties. Most modern systems of thought view the body and soul as a rational whole, the soul is seen as actively shaping and organizing the body.[36]

Under these influences there occurred a steady move toward the acceptance of the theory of immediate animation. This acceptance reached its zenith within official Catholic teaching in 1869 when the distinction between the unensouled and the ensouled embryo-fetus was removed from canon law. The Catholic Church seemed to state definitively that the soul is infused at the earliest possible time—at fertilization.[37] Since that time the Magisterium has been consistent in its view that a human person exists from the moment of conception.

In Donum Vitae (1987), the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith stated: “From the moment of conception, the life of every human being is to be respected in an absolute way because man is the only creature on earth that God has wished for himself and the spiritual soul of each man is ‘immediately created’ by God; his whole being bears the image of the Creator.”[38]

Ten years later the Pontifical Academy for Life reiterated: “The moment of fertilization marks the constitution of ‘a new organism equipped with an intrinsic capacity to develop itself autonomously into an individual adult.’”[39] This decision was an evolution not only of the philosophical and spiritual arguments over the centuries, but perhaps more importantly, of the rapid advances in the science of embryology.

The most recent formal statement of the Church was released in 2008 again by the CDF: “Although the presence of the spiritual soul cannot be observed experimentally, the conclusions of science regarding the human embryo give ‘a valuable indication for discerning by the use of reason a personal presence at the moment of the first appearance of a human life: how could a human individual not be a human person?’”[40]

By the latter half of the twentieth century it was clear that from the time of fertilization the complete genetic complement of a human was present in the embryo. A unique and complete person existed—nothing else was needed.

Discussion

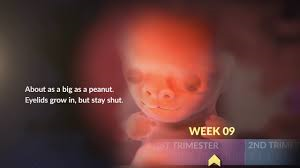

A historical review of the various philosophies and theological concepts of personhood over the past 2,500 years inexorably moved the Church to the position that a person exists from the moment of fertilization. Contemporary advances in the science of embryology have conclusively shown that the complete genetic complement of a human person exists from the time of fertilization. Ultrasound has revealed a heartbeat as early as 21 days after fertilization. A so-called “heartbeat bill” banning abortion once the fetal heartbeat can be detected became law in Ohio in 2019.

The culmination of these philosophical and religious traditions together with the findings of modern embryology was the definitive statement of the Church that the soul is infused at the earliest possible time—at fertilization. Thus, affirming the position that a human person is present from the moment of fertilization. Once conceived, the being was recognized as man because he had man’s potential. The criterion for humanity, thus, was simple and all-embracing: if you are conceived by human parents, you are human.[41]

What the philosophical arguments could not prove, science could. By every objective criteria all the requirements for a human person are present at fertilization. Only time is then required for growth and development.

Within the abortion debate the concept of personhood is generally considered as the status of a human being having individual rights. This was the language used by the Supreme Court in the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision that legalized unrestricted abortion in the United States. Since that time there have been significant advances in the field of embryology. It is these scientific findings that many proponents of restricting/abolishing abortion are hoping will move the populace and the courts towards the position that a human person exists from the moment of conception.

Notwithstanding the hope that modern science may support the view that a human life exists from the time of fertilization, public opinion remains supportive of access to abortion.

In 2019 about 61% of U.S. adults support the view that abortion should be legal in all or most cases. Even a majority of Catholics (56%) also support that view. Only 12% of U.S. adults say abortion should be illegal in all cases.[42] In a 2018 a large proportion of the population (77%) supported abortion in cases of rape or incest.[43] Even in this day of “bargaining” for legal abortion in cases of rape or incest, one cannot trade a human life as recompense for those other evils. It is perhaps this absolute prohibition against abortion that creates such anguish even among the most faithful.

These statistics show that many, perhaps a majority, continue to support the unrestricted availability of abortion. Several states have recently passed laws expanding this unrestricted access to the point of potential infanticide.

Several other states have recently passed laws significantly restricting the availability of abortion. These laws range from absolute restrictions to “heartbeat bills” banning abortion once a fetal heartbeat can be heard, to restrictions after a certain period of time. From a political perspective these laws restricting abortion could only have passed with the support of a significant percentage of the populace. It can be hoped that these recent events signal a national move towards more conformity with the informed teachings and position of the Church.

References

Coughlan, Michael J. 1990. The Vatican, the Law and the Human Embryo. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. 1987. Donum Vitae, I.5.

Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. 1987. Dignitas Personae, FP.5.

Donceel, Joseph F. 1970. “Immediate Animation and Delayed Hominization.” Theological Studies 31(1): 76-105.

Emery, Gilles. 2011. “The Dignity of being a Substance: Person, Subsistence, and Nature.” Nova et Vetera, English Ed. 9(4): 991-1001.

Gallup. 2019. “Abortion.” Accessed October 3, 2019. https://news.gallup.com/poll/1576/abortion.aspx.

Guttmacher Institute. 2018. “Induced Abortion in the United States.” Accessed May 21, 2019. https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/induced-abortion-united-states/.

Kelsey, David H. 1985. “Human Being.” In Christian Theology 2nd ed, edited by Peter C. Hodgson and Robert H. King, 147-175. Philadelphia: Fortress Press.

Lawrence, Cera R. 2008. “Nicolaas Hartsoeker (1656-1725).” Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2008-09-26). ISSN: 1940-5030. Accessed August 25, 2019. http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/1923.

LegiScan 2019. “AL HB314 | 2019 | Regular Session.” Accessed August 22, 2019. https://legiscan.com/AL/bill/HB314/2019.

Michel, A. 1920. “Forme du corps humain.” In Dictionnaire de théologie catholique, (6): 546-588.

National Review. 2019. “Virginia Governor Defends Letting Infants Die.” Accessed August 22, 2019. https://www.nationalreview.com/corner/virginia-governor-defends-letting-infants-die/.

New American Bible. 1991. Washington, DC: Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Inc.

Noonan, J. 1967. “Abortion and the Catholic Church: A Summary History.” Natural Law Forum, 85-131. http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/nd_naturallaw_forum/126.

New York State Assembly. 2019. “Bill A00021 Summary.” Accessed May 21, 2019. https://nyassembly.gov/leg/?default_fld=&leg_video=&bn=A00021&term=2019&Summary=Y&Text=Y.

Ohio Legislature | 133rd General Assembly. 2019. “House Bill 493.” Accessed August 22, 2019. https://www.legislature.ohio.gov/legislation/legislation-summary?id=GA131-HB-493.

Pew Research Center. 2019. “Public Opinion on Abortion – Views on abortion, 1995-2019.” Accessed August 30, 2019. https://www.pewforum.org/fact-sheet/public-opinion-on-abortion/.

Pontifical Academy for Life. 1997. “When Human Life Begins.” Origins 26(40): 662-663.

Tauer, Carol A. 1984. “The Tradition of Probabilism and the Moral Status of the Early Embryo.” Theological Studies 45(1): 3-33.

Torrance, T. F. 1989. “The Soul and Person, in Theological Perspective.” In Religion, Reason and the Self: Essays in Honor of Hywel D. Lewis, edited by Stewart R. Sutherland and T. A. Roberts, 103-118. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

Virginia Legislative Information System. 2019. “House Bill No. 2491.” Accessed August 22, 2019. http://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe?191+ful+HB2491.

Williams, George Huntston. 1970.“Religious Residues and Presuppositions in the American Debate on Abortion.” Theological Studies 31(1): 10-75.

Endnotes

[1] (Guttmacher Institute 2018)

[2] (Gallup 2019)

[3] (New York State Assembly 2019)

[4] (Virginia Legislative Information System 2019)

[5] (National Review 2019)

[6] (LegiScan 2019)

[7] (The Ohio Legislature 2019)

[8] (Tauer 1984, 8)

[9] This theory of Creationism is to be distinguished from that system of beliefs based on fundamentalist interpretations of Genesis which are in opposition to some theories of evolution.

[10] (Williams 1970, 15)

[11] (Donceel 1970, 76)

[12] (Coughlan 1990, 13)

[13] (Williams 1970, 19)

[14] Biblical references unless otherwise noted are from the New American Bible 1991.

[15] (Williams 1970, 19)

[16] (Williams 1970, 19)

[17] (Kelsey 1985, 170)

[18] (Kelsey 1985, 171)

[19] (Torrance 1989, 108)

[20] (Donceel 1970, 77)

[21] Boethius, Treatise against Eutyches and Nestorius, ch. 3 (PL 64, col. 1343). As discussed in (Emery 2011, 994)

[22] (Donceel 1970, 77)

[23] (Donceel 1970, 78)

[24] (Coughlan, 1990, 18)

[25] Thomas Aquinas, Summa theologica 1, q. 118, a. 2. quoted. in (Williams 1970, 30)

[26] Michel, A. 1920. “Forme du corps humain,” In Dictionnaire de théologie catholique, (6): 546-588. Quoted in (Donceel 1970, 87)

[27] (Donceel 1970, 88)

[28] (Donceel 1970, 89)

[29] Pope Sixtus V based his views on the incipient potentiality of the (non-animated) fetus to become a person. See (Donceel 1970, 89)

[30] (Donceel 1970, 89)

[31] In 1961, H. M. Hering, published an article in which he explains that quite a number of authors consider the delayed animation theory “wholly given up as antiquated and less probable, even, according to some, as certainly false.” As discussed in (Donceel, 1970, 91)

[32] In the 1617 edition of the Roman Ritual it states: “Nobody enclosed in the mother’s womb should be baptized. But should the infant thrust out its head and should there be danger of death, let it be baptized on the head…. But if he thrusts out some other limb, which shows some vital movement, let it be baptized on this limb, if there be imminent danger.” This formula remains unchanged through the 1895 edition of the Roman Ritual. It was subsequently dropped in the 1926 edition. As discussed in (Donceel, 1970, 90)

[33] (Donceel 1970, 91)

[34] (Lawrence 2008)

[35] A supposed microscopic but fully formed human being from which a fetus was formerly believed to develop.

[36] (Donceel 1970, 94)

[37] (Tauer 1984, 9)

[38] (Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith 1987, I.5)

[39] (Pontifical Academy for Life 1997, 662)

[40] (Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith 2008, FP.5)

[41] (Noonan, 1967, 126)

[42] (Pew Research Center 2019)

[43] (Gallup 2019)