The first, or proto-, martyrs of the Church of Rome commemorate the untold number of Christians put to death under the reign of Nero, in what would ironically later be termed 64 Anno Domini, but which contemporary Romans would have dated 817 A.U.C., ab urbe condita, from the founding of the city in again what we would call 753 B.C. (April 21, to be precise), but for the Romans was year zero.

Nero’s persecution was the beginning of many, Domitian, Trajan, Hadrian, Marcus Aurelius, Decius, Valerian, Galerius, Diocletian, emperors who saw Christianity as a rival to what they saw as their absolute authority over ‘their’ citizens, soul and body, a totalitarianism that continued at least until Constantine, who legalized the Christian religion in 313, but persists into our own day in more subtle and insidious ways (Trudeau’s ‘abortion attestation’ being one recent example), and will until the end of time, ushered in by the ultimate AntiChrist himself, foreshadowed by the innumerable pen-ultimate types, from Nero, to Henry VIII, Napoleon, Hitler, Stalin, all of whom, though different, attempted to control the Church that Christ had founded, one that no earthly power could subdue.

As Pope Saint John Paul II would make clear what was inchoate in the fevered brain of Nero, two thousand years after his reign had crumbled to dust:

The culture and praxis of totalitarianism also involve a rejection of the Church. The State or the party which claims to be able to lead history towards perfect goodness, and which sets itself above all values, cannot tolerate the affirmation of an objective criterion of good and evil beyond the will of those in power, since such a criterion, in given circumstances, could be used to judge their actions. This explains why totalitarianism attempts to destroy the Church, or at least to reduce her to submission, making her an instrument of its own ideological apparatus. (Centesimus Annus, #45)

The tyrants have all failed. Little did Nero know that in slaughtering Christians he was in fact undermining his own power, for the blood of those very martyrs, as Tertullian would write a century and half later, would be the seed of the Church, whose spiritual and transcendent authority would supersede and defy the rights of tyrants to dominate and rule ‘like gods’.

Power and authority went to Nero’s head, as it has gone to the heads of greater and lesser rulers in the intervening Christian centuries (feel free to peruse contemporary accounts of his deviancies, which make for interesting, if disturbing, reading).

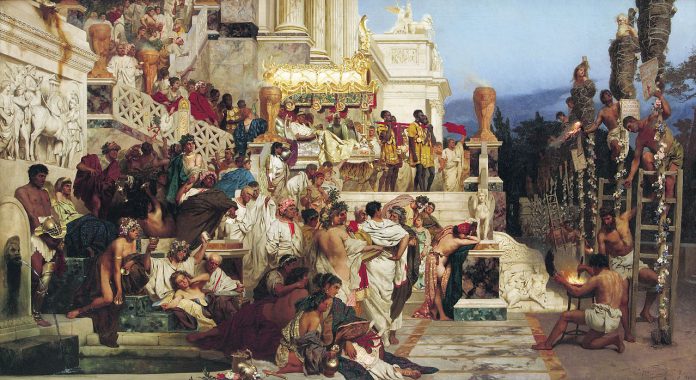

It seems that like many people with too much time and money on their hands, he wanted to enlarge his palace, build ‘bigger barns’ so to speak, and in the process started a fire, whether accidentally or not, one which quickly spread through the city, constructed as in these early years largely of wood. For whatever reason, fear of backlash, or out of spite, or as an excuse to begin his barbarous persecution, Nero blamed the Christians, whom he had put to death in horrific, even satanic, ways, with all the cruelty a twisted soul could devise. As the Roman historian Tacitus, not a Christian, but one who saw the injustice of it all, describes their torments:

Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had expired. Nero offered his gardens for the spectacle, and was exhibiting a show in the circus, while he mingled with the people in the dress of a charioteer or stood aloft on a car. Hence, even for criminals who deserved extreme and exemplary punishment, there arose a feeling of compassion; for it was not, as it seemed, for the public good, but to glut one man’s cruelty, that they were being destroyed.

It seems that Saints Peter and Paul were themselves martyred under Nero’s persecution, Peter, not a citizen, by crucifixion (which he requested be upside down, as he was unworthy to die like his Saviour); Paul, a citizen, by the more dignified method of beheading.

Along with the two pillars of the Church, we have the legions of incogniti, martyrs whose names are unknown to history, but known to God, who rewarded their witness with an eternity of ineffable happiness.

Vita brevis, aeternitas longa. Life is short, along with the sorrows thereof, but eternity is long, and Saint Paul, as he was about to pour out his life, saw clearly that the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory that is to be revealed to us.

We will have our own persecutions, perhaps not like those Nero offered, but there is more than one way to be thrown to the lions, and they may come upon us like a thief in the night. Hence, Christ’s warning to keep our loins girded and our lamps lit, with our eyes always on the end and purpose of all creation, the Alpha and Omega, which, after all is said and done, is all that really matters.

Holy Martyrs of Rome, orate pro nobis!