While we’re on the theme of athletics, I came across an article claiming that men are 30% weaker now than they were even a scant 30 years ago. Not surprising, one may assume, as the article itself attests, given the increased sedentary nature of our lives, dominated by technology. Most jobs involve tapping upon a keyboard, or moving a virtual mouse over a screen, neither of which is exactly a strenuous activity. The article claims that there were more manufacturing jobs a few decades ago, with such factory work in some way building muscle and stamina.

I take such statistics with a bit of a grain of salt. Forget not that the ‘average’ score is very affected by extremes, so if some men are a lot weaker, or some men are not even ‘men’ (did they include those transitioning individuals who self-identified, I wonder?), then the results will be skewed.

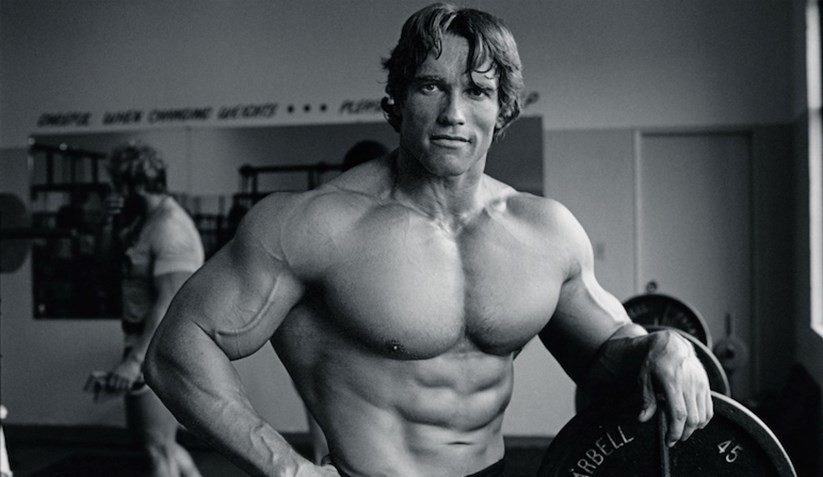

Furthermore, the finding was published in the Journal of Hand Therapy, and the measure they used was grip strength, which is apparently a good indicator of overall strength. Perhaps. I am not an exercise physiologist, but I have pondered what ‘fitness’ and ‘athleticism’ really mean. It is curious that the photo accompanying the article was of a young Arnold Schwartzenegger, in the zenith of his ‘bodybuilding’ days.

The thing is that Ah-nold, for all his muscle, was not really fit. I doubt he could run far, nor could he likely do many chin-ups, and what would he have been like paddling a canoe, hoisting a pack and hiking 20 miles through the forest, working construction, farming? I would take a coureur de bois of early Canada over Arnold anyday; a mere glance at what they could do will give you an idea of what ‘fitness’ really means. For many men (and women) today, health is much about ‘looking good’, perfecting the body into some preconceived mold, fully displayed in spandex.

I will say this for the Olympics and sports, after my recent diatribe on their excesses: They are at least ordered to some kind of objective performance, and not just the vanity of flexing one’s steroid-induced musculature.

And that, I propose, is the point: All of our activity must have a purpose or end, which fits in with the overall ratio or purpose of our life, ultimately eternal beatitude with God. As Saint Paul says, bodily exercise is of some value, but always for a higher good than ourselves, so that we may fulfill our primary vocations more fully and easily. As the poet Juvenal declared, mens sana in corpore sano, a healthy mind in a healthy body.

A healthy adage, I suppose, and one which I try to follow, but as many saints have reminded us, and as this beautiful article recounts on the solemnity of the Assumption (well, well worth a read), health and physical beauty are not necessary for a beautiful and healthy soul. Rather, often the opposite: As we lose the ‘goods’ of this world, we are perforced to focus more on the goods of the next, eternal life, which is why God often sends sickness, ultimately, for all, old age and death, so that we enter heaven, which, as Pope Benedict reminded us in Spe Salvi, is when our real life will begin. Woe to those whose hope is only in this world. We must lose our lives for the sake of Christ and His Gospel, for only so will we find it.

And we should hope Arnold (now in his seventieth year, and who is a baptized Catholic), and all the rest of us perhaps a bit too focused upon our bodily goods, realize this.