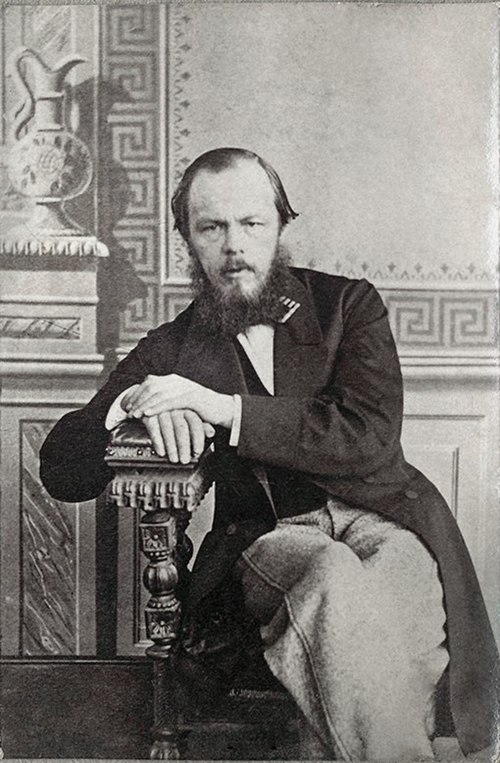

In 1849, Fyodor Dostoevsky stood before a firing squad, fully prepared for death, only to hear his execution sentence revoked at the final instant. This episode serves as more than dramatic biography, since it operates as a key for understanding why Dostoevsky’s writing carries such moral weight, psychological depth, and spiritual seriousness. Few authors ever wrote with the credibility of someone who had already rehearsed his own death and then returned to life with sharpened vision.

Dostoevsky wrote during a period of severe ideological turbulence in nineteenth century Russia. Therefore, imported Enlightenment rationalism collided with Orthodox Christian inheritance, revolutionary socialism, and the ambitions of an autocratic state anxious about dissent. Intellectual circles increasingly treated the human person as a solvable problem, reducible to economic pressures, political structures, or neurological impulses. Consequently, the promise of liberation through theory grew seductive, while moral responsibility appeared burdensome. Dostoevsky entered this atmosphere convinced that ideas were dangerous precisely because they never remained abstract.

His own suffering ensured that conviction carried authority. Arrested for participation in the Petrashevsky Circle, imprisoned, publicly condemned, and subjected to a staged execution, he endured psychological trauma that permanently altered his perception of time, freedom, and grace. Years of hard labor in Siberia followed, accompanied by illness, poverty, and social disgrace. Hence, when Dostoevsky later wrote that “pain and suffering are always inevitable for a large intelligence and a deep heart,” he wrote as someone who had learned this truth bodily rather than rhetorically.[1] Suffering ceased to be an abstraction. It became the terrain on which truth either survives or collapses.

This lived experience shaped his astonishing ability to read the human soul. Dostoevsky grasped that self deception represents the most corrosive moral failure. As he famously warned, “Above all, don’t lie to yourself. The man who lies to himself and listens to his own lie comes to a point that he cannot distinguish the truth within him, or around him, and so loses all respect for himself and for others.”[2] Consequently, his novels expose how ideological certainty often masks internal chaos. Characters speak convincingly while rotting inwardly, which renders his narratives uncomfortable for readers who prefer moral distance.

Nowhere does this appear more clearly than in Crime and Punishment, which remains my personal favorite among his works. The novel functions as a sustained examination of what occurs when moral reasoning detaches itself from transcendent accountability. Raskolnikov’s theory of extraordinary individuals promises liberation from moral restraint, framed as progress for humanity. Therefore, murder becomes experiment rather than crime. Yet Dostoevsky refuses to allow the theory to govern reality. Guilt emerges immediately, relentlessly, and internally, long before any legal consequence arrives.

Through this narrative structure, Dostoevsky reshaped the novel itself. Crime becomes spiritual disintegration before it becomes social violation. Punishment unfolds within consciousness rather than within courtrooms. As Dostoevsky observed, “It takes something more than intelligence to act intelligently,” a line that quietly dismantles the assumption that brilliance guarantees moral clarity.[3] Intelligence unmoored from conscience degenerates into calculation without wisdom.

At the same time, Dostoevsky never relinquishes the possibility of redemption. Darkness fills his pages, yet despair never gains final authority. Sonya’s fidelity, her reading of Scripture, and her willingness to accompany Raskolnikov into exile reveal Dostoevsky’s conviction that grace operates through humble presence rather than ideological conquest. This vision reflects his own post-Siberian faith, forged through suffering and anchored in Orthodox Christianity. He believed that freedom found meaning through responsibility before God rather than self-assertion.

This theological seriousness prevents Dostoevsky from drifting into nihilism, despite his unflinching portrayal of cruelty, obsession, and despair. He understood human capacity for destruction with disturbing clarity, observing that “no animal could ever be so cruel as a man, so artfully, so artistically cruel.”[4] Yet he also insisted that cruelty never exhausts the human story. Grace persists. Conscience resists annihilation. Beauty retains salvific power, captured succinctly in his enduring claim that “beauty will save the world.”[5]

This tension between darkness and grace explains why Dostoevsky remains indispensable. He treats evil seriously without granting it sovereignty. He confronts despair without surrendering to it. He examines political and psychological systems while exposing their inability to satisfy the human hunger for meaning. As he wrote, “The mystery of human existence lies not in just staying alive, but in finding something to live for.”[6] That insight alone separates him from modern narratives that confuse survival with purpose.

Moreover, Dostoevsky grasped the danger of materialistic doctrines masquerading as freedom. His warning remains eerily contemporary: “The world says, ‘You have needs, satisfy them.’ This is the worldly doctrine of today. And they believe that this is freedom. The result for the rich is isolation and suicide, for the poor, envy and murder.”[7] Here Dostoevsky diagnoses the moral trajectory of societies that abandon transcendence while celebrating appetite. Tyranny often follows with bureaucratic efficiency.

Beyond literature alone, Fyodor Dostoevsky reshaped culture, history, and society by permanently altering how modern man understands himself. He focused on the interior drama of conscience. Philosophers, theologians, psychologists, and political thinkers repeatedly returned to his work because he demonstrated that ideology always incarnates itself within the human heart. Therefore, debates about freedom, justice, guilt, and responsibility could never again proceed as though ideas remained harmless or neutral.

His influence reached well beyond Russia. Existentialist thinkers, personalist philosophers, and modern psychologists drew from his insight that the self fractures when severed from moral truth. Moreover, Dostoevsky exposed the psychological roots of totalitarian temptation long before the twentieth century supplied its grim confirmations. By revealing how utopian promises collapse into coercion, he provided cultural antibodies against systems that treat persons as instruments. Artists and novelists learned from him that storytelling could challenge power more effectively than political manifestos, since narrative penetrates conscience where ideology merely persuades.

Most significantly, Dostoevsky restored spiritual seriousness to modern culture. He insisted that suffering carries meaning, that repentance remains possible, and that grace operates even amid collapse. Consequently, he preserved a vision of humanity capable of moral recovery, thereby resisting cultural drift toward despair, cynicism, and dehumanization.

Therefore, Dostoevsky’s life and work function as cultural instruction rather than literary ornament. He demonstrates that storytelling shapes moral imagination more effectively than polemics. He proves that confronting truth demands courage, since “nothing in this world is harder than speaking the truth, nothing easier than flattery.”[8] His witness calls writers, teachers, and evangelists toward seriousness, depth, and sacrifice.

Remembering his spared execution thus carries sobering significance. History nearly silenced a voice uniquely equipped to diagnose modern moral confusion. Instead, that voice endured, chastened by suffering and sharpened by grace. Dostoevsky teaches that cultures forgetting God soon forget why life possesses dignity, why suffering demands meaning, and why freedom requires moral order. From that forgetting, coercion advances swiftly. Materialistic tyranny requires only one additional step.

Dostoevsky saw this clearly because he stood on the edge of death and returned convinced that every moment carries eternal consequence. His novels remain urgent because the conditions he diagnosed persist. His witness urges us to evangelize with imagination, to teach with intellectual honesty, and to engage culture at the level of conscience rather than slogan. He reminds us that truth, goodness, and beauty remain inseparable, since when God fades from view, everything that renders society worthwhile soon follows.

[1] Fyodor Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment, trans. Constance Garnett (New York: Modern Library, 1950), 565.

[2] Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, trans. Constance Garnett (New York: Modern Library, 1950), 316.

[3] Fyodor Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment, trans. Constance Garnett (New York: Modern Library, 1950), 27.

[4] Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, trans. Constance Garnett (New York: Modern Library, 1950), 256.

[5] Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Idiot, trans. Constance Garnett (New York: Modern Library, 1950), 573.

[6] Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, trans. Constance Garnett (New York: Modern Library, 1950), 298.

[7] Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, trans. Constance Garnett (New York: Modern Library, 1950), 84.

[8] Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Idiot, trans. Constance Garnett (New York: Modern Library, 1950), 493.