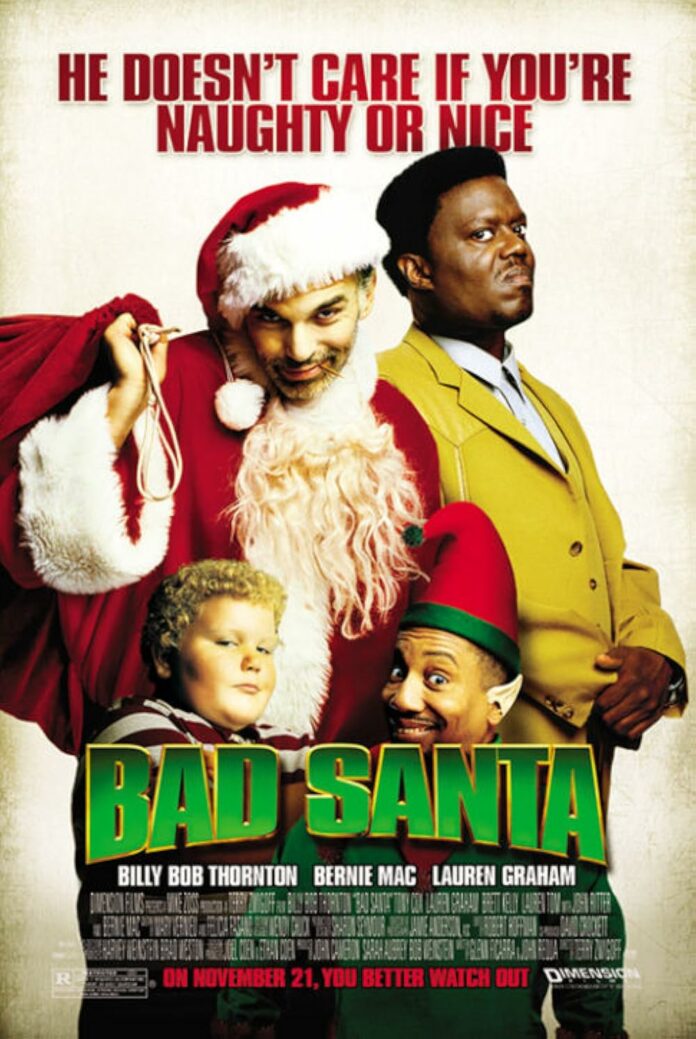

A Christmas Reflection on Evil, Freedom, and Redemption in Bad Santa

Editors’ note: the film reviewed below contains explicit sexual and violent scenes, sustained crudity and profane humor. This review is not meant to serve as a recommendation, but rather as an example of the application of Christian principles to morally disordered narratives to seek deeper truths about freedom, vice, and the possibility of grace, even accidental grace. It should be watched with caution, if at all.

Christmas films are traditionally designed to uplift. From It’s a Wonderful Life and A Christmas Carol to lighter fare such as A Christmas Story, Home Alone, or even All I Want for Christmas, the genre typically trades in warmth, reconciliation, and reassurance. Bad Santa, in many instances, does the opposite, plunging instead into darkness and crass humour.

When I first saw it at a friend’s birthday gathering just before Christmas in 2003, I was not shocked in the way I perhaps should have been; in those days I was more desensitized to crudeness than I realized, yet something in the film still troubled me. I have seen it since, along with the sequel, and in doing so managed to approach it as an exercise in seeking grace in unlikely places.

For years, I have had it in the back of my mind to write something theologically meaningful about this unlikely film, especially as I have contributed several Christmas reflections for Catholic Insight over the years. It is worth mentioning that this essay differs radically in tone and context from my recent reflection that I offered on December 11th, 2025: In the Stillness, We Find Christ. In that essay, I approached the mystery of Christmas through silence and interior attentiveness, whereas the present piece traces grace as it erupts amid noise, disorder, and depravity. The film was dedicated to John Ritter, who passed away shortly before its release. Several years later, Bernie Mac passed on as well adding a sense of fragility and a reminder of our shared mortality beneath all the chaos evoked.

The film’s main character, Willie Soke, is a career thief who poses as a mall Santa each December to rob shopping center safes alongside his partner Marcus Skidmore, a sharp-witted, foul-mouthed dwarf whose disciplined performance as the Christmas elf masks a colder efficiency. The two repeat the same scheme year after year, drifting from city to city across the United States in order to stay ahead of the law.

Willie’s safe-cracking skills come from his father, a tragic inheritance of talent woven into dysfunction. The film’s early scenes establish the pattern of their crimes, opening with a successful mall robbery and its aftermath before jumping ahead to the following Christmas season and a new mall in Pheonix. This is where Willie and Marcus encounter Bob Chipeska, the gentle, awkward, and overly polite mall manager played by John Ritter. Chipeska is a man anxious to preserve decorum. He clearly senses that something is amiss. His discomfort reveals an important feature of the film’s moral landscape: those who appear respectable often lack the courage or discernment to confront real degeneracy. Something that is echoed all too often beyond the screen.

Willie himself is nearly destroyed by alcoholism, promiscuity, rage, and despair. Nevertheless, the film slowly discloses that beneath this moral and emotional ruin remains the fragile outline of a soul not completely shut off to the good. This becomes clear when Willie encounters Thurman Merman, played by Bret Kelly, a painfully innocent, socially awkward, overweight, and relentlessly bullied child. Thurman’s life is rather tragic. He lives with a grandmother who is no longer fully present to reality; his mother has died, and his father is incarcerated for embezzlement. His vulnerability exposes the quiet cruelty of a world that neglects those least able to defend themselves.

Thurman’s vulnerability is expressed not only in what he lacks but also in what he tries, awkwardly, to give. Longing for connection, he spends his time hand-crafting a crude wooden pickle ornament as a Christmas gift for Willie, an offering as earnest as it is ill-suited. In the process, he cuts his hand badly, leaving the small workshop splattered with blood. Willie, hungover and barely conscious, responds by pouring vodka over the wound as a makeshift antiseptic. The moment is undeniably grotesque, yet it reveals the earliest flicker of concern in a man who has nearly drowned his conscience.

Their relationship deepens through moments of both crisis and quiet vulnerability. One of the most revealing scenes occurs when Thurman shyly shows Willie his report card and asks, “Do you think I did well?” Willie tries to deflect the question, muttering that it should not matter what he thinks, but then concedes the boy has done better than he ever did. Thurman admits that he hoped doing well in school might mean he would receive a Christmas present this year, since none came in the previous two. The confession wounds Willie more than he expects. When Thurman, overwhelmed by his own sense of worthlessness, calls himself a loser, Willie suddenly erupts, not in anger at the boy, but at the tragic circumstances that have formed him. Willie insists he is not Santa Claus and is living proof that there is no such innocence in the world. After a long pause, Thurman quietly replies, “I know there’s no Santa. I just thought maybe you would want to give me a present because we’re friends.” That final line pierces Willie’s cynicism. Thurman is not appealing to fantasy but to relationship. In that moment, Willie confronts the remnants of goodness buried beneath years of self-destruction.

The Christian tradition offers conceptual clarity to what the film depicts in rough narrative form. Augustine insists that evil has no independent substance: “For evil has no positive nature; but the loss of good has received the name ‘evil’” (City of God, Book XI, chapter 4). Evil is not a rival power to the good but a falling away from the order that gives human action its meaning. Anselm articulates this moral structure in terms of rectitude of will. In On Truth, he defines justice as “rectitude of will preserved for its own sake” (De Veritate, 12) and understands sin as the abandonment of this rectitude in favour of lesser goods.

In my mind, one could compare this dynamic to Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, where the giving of a gift functions as a sign of human relation and moral awakening. Like Scrooge, Willie is confronted not by argument or reprove but by the quiet persistence of vulnerability, which draws him back into communion with another. The difference, of course, is that where Dickens offers moral lucidity and warmth, Bad Santa stages this recognition amid chaos and degeneracy, demonstrating that the logic of redemption can still operate even when the setting is profoundly damaged.

That fragile reawakening, however, unfolds alongside profound inner turmoil and despair. Shortly afterward, Willie attempts to take his own life by carbon monoxide poisoning in his stolen car at Thurman’s house. Before doing so, he leaves the boy a note confessing his crimes and implicating Marcus and his wife, a final act that, while not genuine repentance, reflects a tortured impulse toward truth rather than concealment. The attempt fails, and in a moment of drowsy, half-conscious clarity brought on by the carbon monoxide filling the garage, Willie regains just enough awareness to survive. He later notices Thurman with a black eye, the visible mark of ongoing bullying. Willie’s immediate and visceral concern for the boy’s wellbeing signals that his moral conscience, though battered and long suppressed, has not been fully extinguished and is now struggling back into action. In Augustinian terms, this concern reveals that even a will long bent inward on itself remains ordered toward the good it was made to love, while Aquinas would recognize here the persistence of natural law within the conscience, however obscured by vice.

The film then cuts to Willie confronting the boys responsible. What follows is not justice but violent reaction. Willie beats them savagely, an act that is morally indefensible but psychologically intelligible, the violent misdirection of a will that has begun, however faintly, to turn outward toward the protection of another.

It is only after these events that the film introduces a darkly comic but revealing exchange between Willie and Marcus. When Marcus later encounters him, Willie announces with misplaced pride, “I think I turned a corner. I beat up some kids today.” Marcus responds flatly, “You need many years of therapy. Many years of therapy.” Even in moments of humour may lie deep truth, such as the ability for disordered actions to provoke the awakening of moral agency. Courage, however awkward, still demonstrates a movement away from moral paralysis and toward responsibility.

The film’s starkest moral contrast emerges through Gin Slagel, the mall’s head of security, played with sharp restraint by Bernie Mac. Gin is an incessant chain-smoker, who gulps down Metamucil, and prowls the mall with suspicion. Although he is ethically compromised; he’s not malicious. He is merely a man navigating a morally gray environment with imperfect judgment rather than cruelty. When he uncovers Willie and Marcus’s operation, he confronts them with a questionable proposal instead of immediately turning them in. Marcus’s response is chilling. Rather than negotiate, retreat, or hesitate, Marcus and his wife execute Gin in cold blood behind the mall dumpsters. Their subsequent attempt to murder Willie confirms that this was no moment of panic but the settled expression of a will long at ease with violence.

Marcus embodies what St. Thomas Aquinas describes as the deformation of moral life through habituated vice, as we shall see below, a process that modern neuroscience increasingly confirms at the level of the brain itself. For Aquinas, vice is not merely a collection of isolated wrong acts but a settled disposition that reshapes the soul over time. As he writes, “Vice is a quality in respect of which the soul is evil, even as virtue is that which makes its subject good” (Summa Theologiae I–II, q. 71, a. 1). He further teaches that “sin diminishes the good of nature,” especially the natural inclination toward virtue, by weakening reason and distorting the will (Summa Theologiae I–II, q. 85, a. 1). Over time, repeated disorder does not simply coexist with reason; it reshapes perception itself until the good no longer appears as good at all. In The Screwtape Letters, C.S. Lewis warns that the gravest danger is not dramatic wickedness but gradual moral shrinkage, a descent along a “gentle slope” where the soul becomes incapable of recognizing anything beyond its own appetites: “Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one — the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts” (Screwtape Letters, Letter XII). Marcus exemplifies this narrowing. Willie, unexpectedly, does not.

Contemporary research on neuroplasticity actually provides empirical support to these moral insights. In The Mind and the Brain: Neuroplasticity and the Power of Mental Force, neuropsychiatrist Jeffrey M. Schwartz shows that repeated patterns of attention and behaviour physically rewire neural pathways, such that the brain is gradually shaped by what the mind repeatedly chooses. As an interesting sidenote, this is why Jeffrey Schwartz’s work has proven so effective in treating obsessive–compulsive disorder. By teaching patients to redirect attention and behavior, he demonstrates how deeply ingrained patterns can be loosened and reshaped. His approach even found its way into popular culture through The Aviator, where Leonardo DiCaprio’s portrayal of OCD was informed by Schwartz’s research. Norman Doidge documents the same phenomenon in The Brain That Changes Itself. In it he documents how habitual behaviours reinforce certain neural circuits while weakening others, eventually narrowing perception, impulse control, and moral awareness. In this sense, Marcus and his wife do not simply commit evil acts. They become the evil act since the persist in their refusal of the good, where guilt, restraint, and repentance no longer exist as clear options. As Lewis explains:

“I would much rather say that, every time you make a choice, you are turning the central part of you, the part of you that chooses, into something a little different from what it was before. And taking your life as a whole, with all your innumerable choices, all your life long you are slowly turning this central thing either into a heavenly creature or into a hellish creature: either into a creature that is in harmony with God, and with other creatures, and with itself, or else into one that is in a state of war and hatred with God, and with its fellow creatures, and with itself. To be the one kind of creature is heaven: that is, it is joy and peace and knowledge and power. To be the other means madness, horror, idiocy, rage, impotence, and eternal loneliness. Each of us at each moment is progressing to the one state or the other” (C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, Book III, ch. 4).

As the final heist begins to unravel, the moral divide between Willie and Marcus becomes unmistakable. Before police arrive, Marcus turns his pistol on Willie and calmly prepares to kill him. The conversation that ensues is what is most revealing about the shape of Marcus’s moral world and soul. Marcus berates Willie for having become unreliable, for drinking too much, and for failing year after year to maintain discipline. Willie does not deny his failings, but he does challenge Marcus on something more fundamental. Gesturing toward the piles of stolen goods, he questions the need for all of this stolen merchandise. It is Christmas, Willie insists, and he asks whether Marcus really needs all of this.

Marcus’s response exposes the depth of his moral deformation. This, he insists, is what they do. Christmas is not a season that interrupts their habits but one that intensifies them. Theft, accumulation, and violence have become routine, bound up with his sense of masculinity and identity. He calls on his wife to shoot Willie without hesitation. Marcus does not act in panic or confusion but with cold deliberation. Willie understands what is coming and does not meaningfully resist. The threat of death is imminent, interrupted only by the sudden arrival of police, alerted by the note Thurman has delivered, the same note in which Willie confessed his crimes and implicated Marcus and his wife. Marcus flees without remorse.

It is in the aftermath of this confrontation that Willie’s final choice takes shape. Earlier in the movie, when Willie asked Thurman what he wanted for Christmas, the boy hesitated and then quietly requested a pink elephant, an oddly specific and childlike desire that shows innocence rather than greed. As alarms sound and police swarm the mall, Willie abandons the robbery, grabs the pink elephant, and flees in his car, not simply to escape arrest but to keep a promise made to a child. His flight is not an act of self-preservation but of fidelity.

Charles Taylor helps name what is at stake here at the cultural level. In a disenchanted age shaped by what he calls the “immanent frame,” transcendence is often eclipsed and moral horizons fold inward (A Secular Age). Marcus inhabits this closed moral world completely. Willie does not. His willingness to suffer for the sake of another reopens a horizon that points beyond himself. In that sense, the pink elephant is not merely a gift. It is a sign of recovered transcendence, however tentative.

Willie races back to Thurman’s home, still dressed as Santa and unarmed. When he reaches the doorstep and attempts to deliver the gift, he is shot repeatedly by police in full view of a neighbourhood of children. The scene is deliberately unsettling. Whatever Willie’s crimes, the image of an unarmed Santa being gunned down while delivering a child’s Christmas present exposes a ruin of moral proportion and judgment that extends beyond Willie alone. He survives his wounds, but survival is almost beside the point. The contrast between Willie and Marcus thus echoes, in a rough and secular register, the two criminals crucified beside Christ. One remains locked in mockery and bitterness, refusing grace even in extremity. The other, with nothing left to offer but acknowledgment and trust, turns toward mercy. These two figures represent the permanent human possibility. Every person stands between these orientations of the will: refusal or consent. Marcus resembles the unrepentant thief, hardened and enclosed within himself. Willie resembles the penitent thief, who even in ruin turns toward compassion and truth. What matters is that, under mortal threat, Willie chooses the good of another over his own safety.

Outwardly, the gesture borders on the absurd. Inwardly, it is a moral breakthrough. For the first time in years, Willie wills the good of another at real personal cost. This is not moral heroism in the conventional sense, nor does it erase his long history of vice. But it does mark the first genuine reordering of his loves. As Augustine famously observes, “My weight is my love; wherever I am carried, my love is carrying me” (Confessions, XIII.9). Willie’s life has long been carried by disordered loves, but in this final act it begins, however falteringly, to be carried toward what ought to be loved.

Redemption does not require perfection. It requires consent. It begins the moment a person wills the good, even once, even imperfectly. Marcus shows what becomes of the will that consistently refuses such movements. Willie shows what becomes possible when even a small opening to grace is allowed. The pink elephant, ridiculous as it appears, becomes a small icon of Christmas hope. It is the unlikely gift of a man who has finally chosen love over despair and a reminder that no one is beyond redemption as long as the will can still turn.

Christmas proclaims that Christ enters precisely such places of deep fallenness. He comes not for the righteous but for the Willies of the world, whose faint gestures of goodness reveal that the divine image still burns beneath layers of brokenness. As long as the will retains even a spark of openness to the good, redemption remains possible. Grace can rise in the gutter. And no sinner, however fallen, is beyond the reach of Christ’s mercy.

A Merry Christmas to all!