Child of These Tears

by Molly McNett

Slant Books, October 1st, 2025

For an excerpt, see the Slant webpage here

Being human is being peculiar to all of creation. We have a body that tends toward the way of all flesh, that wilts and fades. But we have too a spirit, akin to the angels, which soars upward, always seeking. Our restless, at times uneasy, existence faces many moments where we, as Prof. Molly McNett might say, cleave our self in two. We do it all the time.

The man who clocks in cleaves himself from the family man. The teacher splits himself in two: speaking to his students one way and to his superiors another. The public façade; the private sanctum. The will to do what is right; the will to do what we want. Infinite pairings persist. At their worst, these are at odds with each other.

Such was the case of the hungry beggar in Mark Twain’s Joan of Arc, a subject of pity for the young title character, who said of him: “…it is that poor stranger’s head that does the evil things, but it is not his head that is hungry, it is his stomach, and it has done no harm to anybody, but is without blame, and innocent, not having any way to do a wrong.” One part of him works vice; another, no harm at all. Such is the case similarly of young Constance, the protagonist of McNett’s latest literary contribution, Child of These Tears. Constance must try to distinguish and parcel out the good and the bad.

SHE CLEAVED HERSELF in two. The wicked part she hid from Mother and Father, but when it grew angry, or showed its greed or immoderate affection, she was ashamed, and wished that the wicked part would perish, along with all sinful things…But perhaps she did not truly wish this.

That last line is telling. It’s more true to reality. It gets at what St. Paul said, “For I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate. For I know that nothing good dwells in me, that is, in my flesh. For I have the desire to do what is right, but not the ability to carry it out. For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I keep on doing” (Romans 7:15, 18-19, ESV).

Though the spirit be willing, the flesh is weak. This common factor of the human condition recurs throughout this fascinating, quick-paced novel. Constance is torn from her family by an Indigenous tribe and taken to French Canada. They are cleaved in two. Fr. Floquart is a man filled with quaint hypocrisies common to us all. His “necessary” comforts; his quest to abnegate himself. Sarah Baker, Constance’s mother who travels a great distance with her after being captured, balances her anxieties in her mind. Worry regarding if/when they will be rescued; worry regarding keeping up Constance’s courage and safeguarding her well-being. John Baker, the stern father paralyzed by grief, teeters between action and inaction. Writing in his commonplace book filled with marks and maxims; desiring the return of his wife and daughter and doing something about it. He is cleaved in two.

Later, Constance cleaves herself in two in myriad ways. English or Mohawk? Calvinist or Catholic? Constance or Skentsiese – or was it Marguerite-Ange? These are some of the paths she must pick between. Through it all, who or what is family? Constance and her family (biological parents and adoptive mother “Nistenha”) are victims of depression, heartbreak, infant loss, shock, and PTSD. Their grief and trauma lend one of the unifying threads to this colorfully woven story. Even Fr. Floquart, a grown man, carries hidden scars from the separation from his mother in his youth.

The human mind can ponder, remember, realize, memorize, synthesize, summarize. It is pliable and teachable; it is also resistant and looks out for itself. Modern medicine recognizes how trauma can trigger memory loss. The people of the 18th century did not have a framework to discuss or cope with mental health challenges, a concept that eludes many in our current society as well. McNett tackles this reality head-on in her eloquent words and images and those of the thinkers of the past.

The mind’s resilience sometimes allows it to block out undesirable memories. We even compartmentalize things that aren’t emotionally scarring, all our accumulated knowledge and experience. We compartmentalize. We place the things within an imaginary box or room within our minds. St. Augustine of Hippo pictures the “huge repository of the memory” in terms of “fields” or “vast mansions” or “caverns.” McNett borrows a compartmentalization image from St. Teresa of Avila, that great Spanish mystic who has inspired many other creative writers, including Virginia Woolf and Kate O’Brien. The image is that of the Interior Castle with its seven mansions within the “castle” of the soul, symbolic of areas for growth in the interior (spiritual) life, leading ultimately to God Himself, the source of light and beauty.

This is an image used by the character Fr. Floquart in his writings. A similar image, an interior home – her English parents’ house to be exact – is Constance’s mind palace of sorts. Here reside mementos of bygone moments, things both latent and vivid, depending on how her mind suppresses the traumatic ones. Here’s a sample:

This was a goodly thought. She fashioned it as she marched, and was amazed, for God had preserved the corner pantry in her mind and in it the pewter plates and cups and the stone jug with its ears for handles, and there were many things on the shelves that she could remember.

She remembers numbers up to a thousand and the beads of her catechism, but other areas seem obscured.

She could see the rooms of the house darkly, but when her mind walked closer, to see what had passed there, the others went down the cellar stairs, into the blackness.

Two powerful experiences every human being must contend with are these: We are the recipients of suffering; we are also the recipients of beauty. We can all suffer bodily torment and mental anguish. Though the characters’ motivations vary, they’re united in their capacity for suffering. We are equally capable of being receptive to the beauty around us. It is beauty, which permeates and transcends the mundane, that supplies the second unifying thread to McNett’s silver storyline web. Beauty speaks to Catholic and Calvinist, Indigenous and European, child and adult alike. It draws them (and us) into mystery.

The Jesuit missionary Fr. Floquart, to whom I relate most closely, gets very philosophical about beauty in his letters. Nature, the monstrance, a hand-drawn picture: all contain beauty. Constance sees beauty in moon and mist, language and literature. Her mother, Sarah, sees it in the frozen, sparkling countryside:

…removing a mote from the eye, allows us to see the world’s beauty most clearly, and, still sorrowing, we are bound in all at once. I offer this as a testament to divine providence…

This transcendent quality points to God, who is, as St. Francis of Assisi believed, love, peace, joy, gentleness, and beauty Himself. Perhaps it is in part through beauty that “The world is literally dripping with grace” as Eric Clayton would have it. Or, as Joshua Hren observes, “Nature is sacramental, shimmering with signs of sacred things. Indeed, all reality is mysteriously charged with the invisible presence of God.”

Fr. Floquart is under the impression that beauty speaks to the heart and is a necessary aid to effective evangelization. I agree. So does the Catholic novelist, poet, musician, and artist. Though not a Catholic herself, McNett steeped her imagination in the mystic writings of the saints and letters of the early Jesuit missionaries (the complaints of whom she quickly picked up on as had Thoreau over a century and half ago) as part of her research for the novel. The beauty of her own writing serves as an example of fine literature. She also immersed herself in the Indigenous habits of the day and the personal lives of Westerners from the same era.

In the voice of the fictitious Floquart, McNett speaks like a cradle child of the Church. She has written one of the finest Catholic novels in recent years. (One does not need to be Catholic to do this. Please see Mark Twain’s critically acclaimed Joan of Arc cited above.) The book is written in fragments, much like the various pieces of Constance’s hectic childhood, and in the voice and format of the contemporaneous media which McNett studied from the depicted era of European pioneers. Those fragments exist as letters, written accounts, excerpts from John Baker’s commonplace book, and introspective reflections on Constance’s experiences (her “mind palace,” her dreams, her daily life among the Indigenous people). Bit by bit we are fed the story. The tale changes perspectives regularly, which keeps the reader engaged and makes for a quick read.

In this way, the author presents a novel that is at once old and new. It is old in the sense that it appears in the style of written correspondence that was in vogue in the early 1700s. This same ingenious mode of delivery, primarily through concise letters, feeds our modern minds with their dwindling attention spans. Have you picked up a James Patterson novel recently? The one I’m currently reading (Eruption, completed from a concept by Michael Crichton) averages four pages per chapter. The average “chapter” (or letter usually) in Child of These Tears is even shorter. In this way, McNett might be said to have struck the balance our Lord Jesus asks of Christian writers when He proclaims, “Therefore every scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven is like a master of a house, who brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old” (Matthew 13:52, ESV).

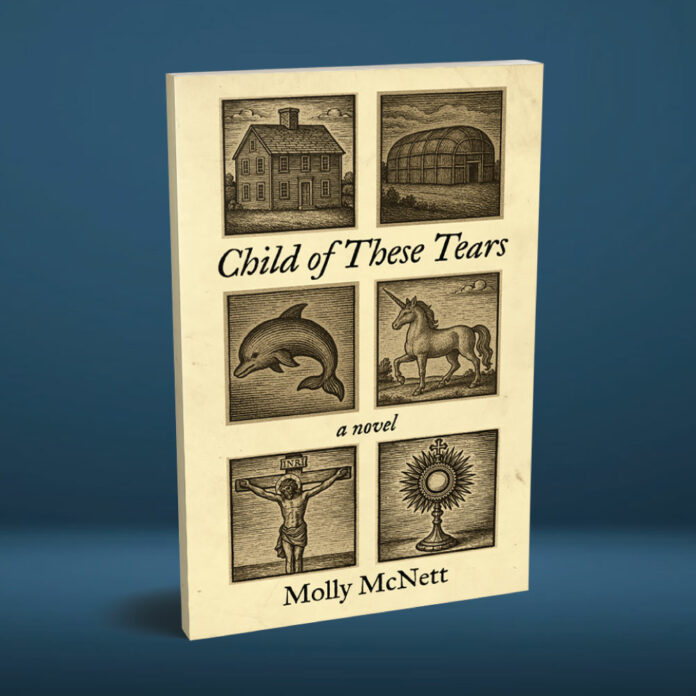

Even the design of the book follows an aesthetic that’s both old and new. The type was set in a style reminiscent of one used by Oxford University Press over 400 years ago. Meanwhile, the images that make up the cover, which I found so enthralling and engrossing, were generated using ChatGPT, the AI model taking the world by storm. The antiquated and the cutting-edge meet. Readers caught up in Constance’s fractured world hope that justice and peace shall kiss. You will find Child of These Tears gripping, stirring, and – just like the way Constance feels about the simple pleasures in life – “most delightful.”