“With particular seriousness he added that it was questionable whether the coup would succeed, but even worse than failure would be the shame of submitting tamely to oppression and allowing oneself to be paralyzed by it. Freedom, both internal and external, could only be won by action.” – A German officer’s description of his conversation with Claus von Stauffenberg.[1]

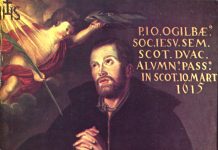

2024 marked eighty years since the so-called “July plot” or “July 20 plot”, the final and most involved attempt to assassinate Adolf Hitler and overthrow the Nazi regime. The eighty-first anniversary having just passed, it behooves us to spare a moment to reflect upon the plotters and their families. The daring actions of July 20, 1944 were, at least for many, the fruit of deep-seated love of country and even faith. Those with the seemingly super-human bravery to act against hope endangered not only themselves but also their loved ones. Especially for us Canadians, for whom it is very easy to find reasons to complain about the state of our nation, the story of the July 20 plot may offer some inspiration and encouragement. Thanks be to God, conditions here are not quite the same as those of Hitler’s Germany. On the other hand, we do seem to be faced by innumerable obstacles to effect any sort of change for the better. Despair, however, is never an option for those with the light of faith, for even our present sufferings and battles can do more good than we imagine when offered as an oblation to Our Lord. Such faith seems to have burned in the soul of the key mover in the attempted coup of 1944, the devout Catholic Colonel Claus Schenk, Count von Stauffenberg.[2]

Contrary to what many seem to believe, the “German Resistance”, as it has been named, was not simply intellectual disagreement up until the July 20 plot. Attempts on Hitler’s life began as early as 1933.[3] In 1938, after years of growing opposition, German officers prepared to rally the army and take control of the government if Hitler attempted to invade Czechoslovakia, provided, as was hoped, the western powers would actually stand against him.[4] Among the generals opposed to the invasion of France in 1939, some plotted a similar move to kill Hitler and negotiate a peace with the allies.[5] Since the start of the war, however, various obstacles hampered the resistance. Some were unsure if it was moral to break their oaths and assassinate Hitler. Furthermore, many wanted guarantees that the allies would, in fact, negotiate with an anti-Nazi government. No one desired a plot that looked like a power squabble. In addition, sufficient control of the army was required to prevent Hitler’s death from creating chaos and civil war in Germany. The conspirators were also plagued by Hitler changing his schedule at will and making his whereabouts unknown in advance. Finally, though earnestly desiring a change of regime, many were hesitant, indecisive, or simply afraid to risk a coup.[6]

In 1943, however, after various failed attempts and setbacks in the resistance, Stauffenberg joined the plotters, though he had already been long opposed to Nazism.[7] That same year, he had lost his left eye, right hand, and two fingers on his left hand. This resulted from injuries while directing retreating German units under allied attack.[8] Despite such handicaps, he was stationed at army headquarters in Berlin, where he found himself in a strategic position to manage a coup. He even secretly prevented the murder of allied prisoners of war.[9] Soon, he became the driving force of the resistance.[10] One of his brothers, an uncle, and two of his cousins had been involved in the 1938 attempt.[11]

Stauffenberg’s Catholicism was not at all separate from his anti-Nazism. On the contrary, the latter sprang from the former. One of the few members of the July 20 plot to survive the war, Fabian von Schlabrendorff, said:

One of the main characteristics of the average German officer was his one-track mind. His concentration on military matters made him incompetent in non-military questions, and particularly in political matters.

In this respect Stauffenberg was different. Army life did not form his horizon. His intellectual interests had led him to the poet Stefan George, the prophet of a “new spiritual elite,’’ who, recognizing Stauffenberg’s inner merit and his mental qualities, had taken him into the circle of his intimate friends. Stauffenberg was influenced by Stefan George’s outlook; he knew much of his poetry by heart, and one of his greatest delights was to recite the famous poem on the “Antichrist.” Stauffenberg’s contempt for Hitler had a spiritual basis. It sprang directly from his Christian faith, which inspired him to take up the fight against Hitler.[12]

According to Elizabeth, Baroness von und zu Guttenberg, a Catholic, who visited Stauffenberg in hospital when he was recovering from his wounds, “He was sure at last in his own mind that in the assassination of Hitler he would be removing a creature actually possessed, body and soul, by the devil.”[13] Even a Nazi SS report called Stauffenberg a “devout Catholic” and declared that his “church ties played a major role in the conspirator’s clique”.[14] One member of the resistance recalls Stauffenberg, who reportedly always wore a gold cross around his neck,[15] as saying “Well, I am a Catholic and we have a long-standing tradition that tyrants can be murdered. You have it too, but not as strong. Luther says you can kill a crazed leader.”[16] On July 19, the night before the coup, Stauffenberg went to confession at a church in Berlin.[17]

The resistance planned long and hard for the July 20 plot to be a success. After Hitler was killed, they would use an emergency plan, code-named “Valkyrie”, to mobilize the reserve army, take control of communication systems, arrest the SS, and install a new government. Valkyrie had been created to deal with internal unrest, such as the rioting of foreign workers, but the resistance would use it to fight an alleged coup by the SS, when, in fact, the resistance would be carrying out a coup themselves.[18] They even involved Pius XII, who had been in contact with the resistance since 1939. The pope agreed to facilitate peace talks with allies, should the attempted overthrow succeed, and recognize the new government.[19] As historian Michael Hesseman says, “The Pope blessed this plan and the conspirators, since it was the fastest way to end the slaughter of six million innocent men, women, and children and the most brutal war in history.”[20] Unlike in other planned coups, the plotters themselves were extremely varied: Officers, civilians, nobility, politicians, monarchists, republicans, communists, socialists, protestants, Catholics.[21]

Despite the preparation, it was still gravely feared that the coup would not succeed. Many, nevertheless, insisted it must still be attempted, whatever the result. Stauffenberg’s brother, Berthold, reportedly declared that, “The most terrible thing is knowing that it cannot succeed and that we must still do it for our country and our children.”[22] Stauffenberg himself stated, “If I did not act to stop this senseless killing, I should never be able to face the war’s widows and orphans.”[23] Either before or during the actual execution of the plot, he is said to have remarked while pointing to a picture of his children, “I’m doing this for them. They must know that there was a Decent Germany.”[24]

Many know well the events of July 20: The bomb placed by Stauffenberg tragically did not kill Hitler, and officers in Berlin stalled the operation of the plan while awaiting confirmation of Hitler’s death or survival.[25] Stauffenberg spurred on his coconspirators till the end. Early on July 21, Hitler broadcasted a radio address condemning the entire conspiracy; he even mentioned Stauffenberg by name.[26] Thus began the relentless hunting and killing of those believed to be implicated, as well as their families. Stauffenberg, along with other members of the plot, were shot early that same morning. It is reported that one of the lower ranked officers rushed in front of him in the line of fire.[27] Stauffenberg cried out before the soldiers shot another time. By some accounts, he yelled “Love live holy Germany” or “Long live sacred Germany”;[28] others report him invoking the words of the anti-Nazi poet Stefan George: “Long live our secret Germany”.[29] In any event, as Schlabrendorff says, “Stauffenberg died with an exclamation of faith in Germany on his lips.”[30]

We are admonished in scripture that, “It is therefore a holy and wholesome thought to pray for the dead, that they may be loosed from sins.” (2 Machabees 12:46) Moreover, it is just and proper that we honour those in the July 20 plot and learn what we may from their actions. History, writes Leo XIII, is “the teacher of life” and “the light of truth”.[31] May we never forget the heroism, patriotism, and faith which inspired those in the plot of July 20, especially that of Claus von Stauffenberg.

Endnotes:

[1] Lieutenant Urban Thiersch, quoted by Joachim Kramarz, Stauffenberg, The Life and Death of An Office: 15th November 1907 – 20th July 1944, trans. R. H. Barry (Worcester and London: The Trinity Press), 154. Originally quoted in Eberhard Zeller, Geist der Freiheit: Der 20 Juli, 4th and fully revised ed. (Munich: Müller, 1963), 361.

[2] On the movie Valkyrie and Stauffenberg’s faith and personality, see Gary Benoit “Valkyrie: The Real Col. von Stauffenberg”, The New American, 4 January 2009, accessed 20 July 2024, https://thenewamerican.com/us/culture/history/valkyrie-the-real-col-von-stauffenberg/.

[3] Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh, Secret Germany: Stauffenberg and the True Story of Operation Valkyrie (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2008), 5.

[4] Ibid., 5-10. See also William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1960), 404-408, 424.

[5] Mark Riebling, Church of Spies: The Pope’s Secret War Against Hitler (New York: Basic Books, 2015), 34.

[6] See Riebling and Shire.

[7] Riebling, 162, and Benoit. See also the excellent, informative documentary “Operation Valkyrie: The Plot to Kill Hitler”, Free Documentary – History, February 26, 2021, 10:00, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z9pD7x-yrf0.

[8] Peter Hoffmann, Stauffenberg: A Family History (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 179-180. Baigant and Leigh, xx-xxi.

[9] Baigent and Leigh, 21.

[10] They Almost Killed Hitler: Based on the Personal Account of Fabian von Schlabrendorff, ed. Gero v. S. Gaevernitz (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1947), 64-66. Baigent and Leigh, xxiv-xxv. Reibling, 161.

[11] Baigent and Leigh, 7.

[12] Gaevernitz, 65-66.

[13] Elizabeth von Guttenberg, Holding the Stirrup, ed. Sheridan Spearman (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1952), 194.

[14] Emphasis in original. Ernst Kaltenbrunner to Martin Bormann, 4 October 1944, in Kaltenbrunner Berichte [Kaltenbrunner Reports], published in Spiegelbild einer Vershwörung: Die Kaltenbrunner-Berichte an Bormann und Hitler über das Attentat von 20 Juli 1944. Herausgegeben von Archiv Peter für historiche und zeigeschichte Dokumentation (Stuutgart: Seewald, 1961), 434. Quoted in Reibling, 163.

[15] Riebling, 163.

[16] Interview with Axel von dem Bussche, Bonn, 6-7 December 1992, quoted by Baigent and Leigh, 158.

[17] Reibling, 190.

[18] Baigen and Leigh, 22-23. See also “Operation Valkyrie: The Plot to Kill Hitler”.

[19] Reibling, 62, 181, 189-190. On the pope’s early involvement see also Hoffman, Stauffenberg, 213, and Shirer, 648.

[20] Deborah Castellano Lubov, “Pope Pius XII: ‘His tiara turned into a crown of thorns,’ says historian”, Catholic World Report, Ignatius Press, 4 March 2019, accessed 20 July 2024, https://www.catholicworldreport.com/2019/03/04/pope-pius-xii-his-tiara-turned-into-a-crown-of-thorns-says-historian/.

[21] See, among other sources, Baighent and Leigh, 20.

[22] Annedore Leber, Das Gewissen steht auf: 64 Lebensbtlder aus dem deutschen Widerstand 1933-1945 (Mosaik-Verlag, Berlin, and Frankfurt, 1960), 126, quoted by Hoffmann, Resistance, 374.

[23] Michael Balfour, Withstanding Hitler (London: Routledge), 109, quoted by Baigent and Leigh, 24.

[24] Reibling., 196. Hoffmann, Stauffenberg, 193.

[25] Baigent and Leigh, 43.

[26] Ibid, 53. Reibling, 197.

[27] Baigent and Leigh, 66-67.

[28] Hoffman, Stauffenberg, 277. Baigent and Leigh, 67.

[29] Baigent and Leigh, 67.

[30] Gaevernitz, 118-119.

[31] Letter Saepaenumero, August 18, 1883 – to Cardinals de Luca, Pitra, and Hergenroether in Papal Teachings: Education, ed. Monks of Solemns, trans. Daughters of St. Paul (Boston: St. Paul Editions 1948), 93.