Recently, Catholic Insight posted a thoughtful note from contributor Carl Sundell on the essential questions we should be prepared to answer about our faith.

This list of questions was likely meant to inspire readers to find and research their own answers to these questions. There are over 2,000 years of resources one could sift through in order to adequately answer and confidently respond.

This inspired me to work through these 39 questions in order to provide clear and concise answers for readers. None of these would, or could, be conclusive, but they may offer initial answers and provide a framework for how others might approach these questions.

I hope that this series proves helpful for you. Let’s start with the first one:

- How many ways can you reply to an atheist who says there is no proof for the existence of God?

The tempting way to respond to this is the fire hose approach and say there are utterly so many ways. This post will provide five simple ways to understand and explain God’s existence. However, unless this first point I am about to make is addressed, it is likely an infinite number of replies will fall on deaf ears.

The first and most important reply “to an atheist who says there is no proof” is to ask what the person means by the word ‘proof’. This is not an annoying “gotcha” to frustrate your interlocutor, but an essential clarification. One of the most common equivocations in the argument about God’s existence comes down to the word “evidence” (especially the word evidence) because it implies an assumption toward scientific materialism.

The term evidence is typically defined in the mind of the person using it as “empirical evidence,” which means that only things that one can see or measure count. This frames the argument in a way that makes it impossible for anyone to prove that God exists because God, as understood by Christians and classical theists, is by nature not something that can be empirically verified – (at least, not in the way modern science understands that term).

This does not mean that there is no way to know if God exists, just that the way of knowing is not the same as the way of knowing about the existence of things within Creation. Another important point to make is that while God is not a part of Creation, and so cannot be proven to exist in the same way as other created things, that does not mean that Creation cannot be used to point one towards God’s existence. In fact, it is abstracting principles that can be applied from observing created things that St. Thomas Aquinas used to reason toward God.

After you have clarified that evidence is more than just things you can see, but the ideas that come from the things you see, you may be able to make some progress in providing some “proof” for God’s existence. Even though there are many arguments (Dr. Peter Kreeft puts forward twenty!), St. Thomas Aquinas has already provided the five simplest ways to God. (cf., Summa Theologica, I, q.2, a.3).

By ‘simplest’, I do not mean simplistic or unsatisfying. By simplest, I mean the proof with the fewest parts while still providing an adequate explanation. Not only has Aquinas provided the fewest parts, he only gives five ways (see Summa Theologiae part I, question 2, article 3), but they all are meant to work together to provide one comprehensive case for God.

In studying the many, many arguments put forward for God’s existence, one also finds that they can each be simplified to one of the five that Aquinas gives. When one understands the five ways of Aquinas thoroughly, one will be able to recognize how contemporary or composite arguments for God can be understood more clearly through the lens of Aquinas.

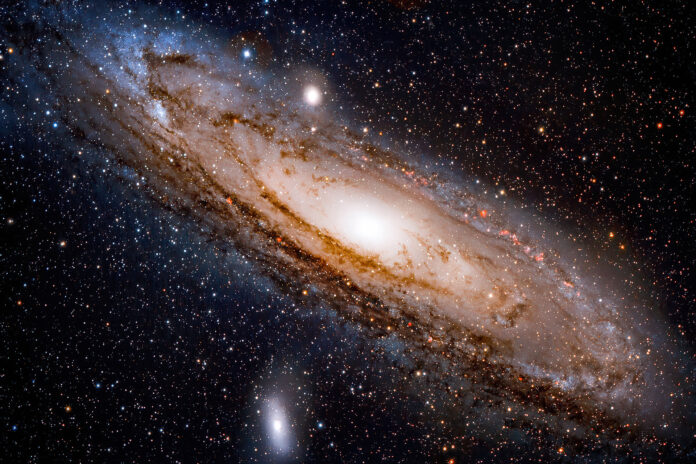

The first way Aquinas derives from Aristotle and refers to the movement we can observe in the universe. We see that everything is moving, including the universe itself, and that everything moves because it has been moved by a power outside of it. The bigger the movement, the more power necessary to move it. If everything within the universe is moved by something outside of it, then, scientifically, it would follow that the universe as a whole would be moved by something outside of it. Also, this Mover would require all the power to move everything, making it omnipotent. This omnipotent, unmoved Mover could be considered God.

(The second way) But what about everything, now? Not only did all of history need to be moved to get to this moment, but even at this moment all of reality is being upheld in existence. From a physical standpoint, gravity is holding the universe together at every moment, not just as something that began it. However, reality is much more than just the physical universe and it is being held together by the ground of reality, or ipsum esse— existence itself, which is what Aquinas, and we, would call God.

The third way goes deeper than the first and second and is a little more abstract. It asks the question of why there is anything at all. We can answer this usually by describing how something came together from not existing to existing. This is the relationship of potency to act. Contingent things move from potentially existing to actually existing and are upheld in existence. In order for there to be anything at all, there must be something without any potency. This thing would be called necessary. This “Necessary Being” would be why everything else exists and qualifies as God.

(The fourth way) Because this Necessary Being causes everything else, all of reality participates in its existence. This includes the real things like truth and goodness. When we recognize a true thing or do a good thing, they participate on a scale of truth itself and goodness itself. We recognize true and good things because this scale, or standard, exists. This scale would necessarily include all truth and all goodness and would be the Standard of Truth, the Standard of Goodness— even the Standard of Being. This Standard is how one knows what is true or what is good. This Standard that conditions all of existence would be called, by nature, God.

The fifth way refers to the purpose we find built into all things— both what we make ourselves and what is found in nature. We can observe that everything acts toward a purpose that exists outside the thing itself. Similar to the first way, if everything within Creation acts toward a purpose, then Creation as a whole acts toward a purpose. If this purpose of all Creation must exist outside of Creation, then it is beyond nature or super-natural. This supernatural purpose of all Creation we, along with Aquinas, would recognize as God.

Be warned that these summaries are all paraphrases of the summaries Aquinas gives himself. There are further questions one can ask and they are based off assumptions that could be challenged (though they are also based on common sense observations we can make and most people accept). They do, however, provide responses to the challenge of God’s existence alongside the important question of “proof” one must ask if being confronted by materialist, atheist objections.

Fortunately, these ways also help prepare one for the very common objection that makes up the second point in Carl Sundell’s list, the problem of evil. This will be covered in the next installment of this series on Apologetics 101.