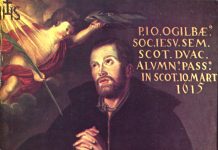

Addressing a United Nations conference on health in 1969 following his reception of the William Allen Award,[1] Dr. Jérôme Lejeune, the discoverer of the chromosomal cause of Down Syndrome, one of the world’s leading geneticists, and a likely candidate for the Nobel Prize in Medicine, stated, “Life is a fact and not a desire.” Lejeune took this opportunity to focus on the dignity of the human person from the moment of conception. He strongly condemned the United Nations’ increasingly anti-life agenda, declaring, “Here we see an institute of health turning itself into an institute of death.” That evening, Lejeune wrote to his wife, “This afternoon I lost my Nobel Prize.”

Jérôme Lejeune was born on June 13, 1926 in the Parisian suburb of Montrouge.[2] In early childhood, he saw the struggles of intellectually disabled children and their families, which proved a formative experience for him. Lejeune received a classical education and was interested in theatre, astronomy, music, and mathematics. He studied medicine and became a researcher at the National Centre of Scientific Research in 1952. In 1957, the United Nations appointed Lejeune to represent France as an international expert on atomic radiation.

Lejeune’s major scientific breakthrough was his discovery of the chromosomal cause of Down Syndrome. This discovery came on May 22, 1958 while Lejeune and Professor Raymond Turpin were researching children then known as “mongols,” who had Down Syndrome.[3] Examining slides with genetic material from these children, Lejeune noted that the twenty-first chromosome pair contained an extra chromosome, meaning that these children had a total of forty-seven chromosomes rather than the forty-six usually present in humans.[4] This was the first link established between an intellectual disability and a chromosomal abnormality.[5] Now, it was clear that Down Syndrome, or Trisomy 21, was not a hereditary genetic disease but was caused by a genetic mutation.

Lejeune’s research was published by the French Académie des Sciences on January 26, 1959, and international recognition followed as its significance was appreciated. In addition to the William Allen Memorial Award, Lejeune received the Kennedy Prize from American President John F. Kennedy in 1962. Lejeune was also appointed to the first chair of fundamental genetics at the Faculté de Médecine de Paris in 1964 at thirty-eight years of age, making him the youngest professor of medicine in France. In 1974, Pope Paul VI appointed Lejeune to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, and in 1981, Lejeune was inducted into the French Academy of Moral and Political Sciences.

Several implications followed from Lejeune’s groundbreaking work. First, it marked the beginning of the modern study of genetics, as well as the inception of the field of cytogenetics.[6] It also led Lejeune to discover the causes of several other genetic disorders, including Cri du Chat Syndrome, 18q-Syndrome, and trisomies of the eighth and ninth chromosome pairs. However, Lejeune’s work was also used to develop prenatal diagnostic techniques to identify children with incurable genetic conditions. While prenatal diagnosis can be beneficial, it quickly became a means to identify children with these conditions so they could be aborted. Currently in the United States, ninety percent of children prenatally identified with Trisomy 21 are aborted. In France, ninety-six percent are aborted, while Iceland infamously aborts nearly one-hundred percent of children prenatally diagnosed with Down Syndrome, with an average of only two or three children with Down Syndrome being born in the country each year for the past decade.

This application of Lejeune’s research was directly opposed to his intention. Lejeune had researched children with Down Syndrome in order to find a cure, and his concern for the rights and dignity of his patients led him to become an energetic pro-life advocate in France and Europe, vigorously opposing the “Culture of Death.” As Lejeune stated, “I am not fighting people; I am fighting false ideas.” Speaking at hundreds of conferences and interviews internationally, he first emphasized that life begins at conception. For example, at a divorce trial in Maryville, Tennessee, in 1989, in which the fate of seven frozen embryos conceived by “in vitro fertilization” was being contested, Lejeune testified that life begins at conception and that the embryos are indeed human. A second theme of Lejeune’s public witness was his defence of the dignity of the human person. He stated, “We need to be clear: The quality of a civilization can be measured by the respect it has for its weakest members. There is no other criterion.” Third, Lejeune emphasized that medicine must be at the service of the patient and that eliminating the patient does not constitute healthcare. Finally, Lejeune spoke against those who reject truth and science in politics to further an agenda contrary to human life. Lejeune stated:

If a law is so wrong-headed as to declare that “the embryonic human being is not a human being,” so that Her Majesty the Queen of England was just a chimpanzee during the first 14 days of her life, it is not a law at all. It is a manipulation of opinion, and has nothing to do with truth. One is not obliged to accept science. One could say: “Well, we prefer to be ignorant, we refuse absolutely any novelty and any discovery.” It’s a point of view. I should say, it’s a “politically correct” point of view in some countries, but it’s an obscurantist point of view, and science abhors obscurantism.”

Clearly, Lejeune was unambiguous: Human life begins at conception and must be respected from that moment. Any medicine or law which does not accord with this simple principle contravenes the truth and must be opposed.

Lejeune’s bold, uncompromising defence of life was particularly courageous because it directly opposed the zeitgeist of his culture, embodied by the Sexual Revolution and societal upheavals of the 1960s. The Sexual Revolution is commonly dated from the approval of “the Pill,” the first oral hormonal contraceptive, by United States Food and Drug Administration in 1960. In the Sexual Revolution, societal attitudes hardened against traditional sources of authority, particularly the family, Church, and State. The Revolution progressed through the international movement to legalize abortion and initiated the rapid decline of family life which has continued to the present.

One particular example of the social unrest and volatility resulting from the Sexual Revolution in Lejeune’s native France was the May 1968 student revolution. A student revolt against societal authority, the May 1968 revolution drew inspiration from Communist revolutionaries and was both violent and disruptive. The unrest began in 1967 in student protests in Paris over dormitory restrictions which prevented sexual relations between male and female students. Events escalated, culminating in violent confrontations between Parisian police and the student mob in May 1968.

Lejeune’s uncompromising courage in opposing the spirit of his age came at a personal cost. In addition to not receiving the Nobel Prize in medicine, Lejeune was publicly derided. He was ridiculed in the press, and during the May 1968 student revolution, student protestors wrote graffiti on the walls of his university, reading, “Tremble, Lejeune! The Revolutionary Student Movement is watching!” and “Lejeune and his little monsters must die!” Additionally, Lejeune experienced professional ramifications. Despite his status as an international expert, he was no longer invited to speak at international genetic conferences, his research funding was cancelled, and other scientists would not collaborate with him, forcing him to disband his laboratory and research team.

While Lejeune’s defence of life caused him to become a social pariah in popular culture and the scientific community, it gained him the friendship of one of the twentieth-century’s greatest men: Pope John Paul II. Lejeune became good friends with the Pope. Interestingly, Lejeune and his wife had lunch with Pope John Paul on May 13, 1981, the Feast of Our Lady of Fatima, hours before the Pope survived an assassination attempt by Mehmet Ali Agca in St. Peter’s Square. Lejeune also served as an occasional papal diplomat. In 1981, he was deputed by the Pontifical Academy of Sciences to brief Leonid Brezhnev, General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party, on the dangers of atomic warfare. Also, in 1984, he served as papal representative at the state funeral of Yuri Andropov, Brezhnev’s successor as leader of the Soviet Union.

John Paul also appointed Lejeune first chairman of the Pontifical Academy for Life. Lejeune originally declined, as he had recently been diagnosed with lung cancer. However, when the Pope insisted, Lejeune acquiesced, stating, “I will die in action.” He drafted the Academy’s bylaws and wrote the oath of the Servants of Life, taken by all members upon entry into the Academy. Lejeune served as chairman from February 26, 1994 until his death thirty-three days later. He went to his eternal reward on April 3, 1994 – Easter Sunday. The spiritual significance of this was not wasted upon his friend, the Pope, who wrote, “That the Heavenly Father should have summoned him on the very day of the Resurrection of the Lord must surely be no mere coincidence, but in itself a veritable sign.”

Dr. Jérôme Lejeune’s cause for canonization was opened on June 28, 2007. His spiritual significance within the modern Church lies in the fact that he is an exemplar of a faithful Catholic professional. At the pinnacle of his profession as a scientist, physician, and researcher, Lejeune demonstrated integrity of life, uniting orthodoxy and orthopraxy. While many of his contemporaries rejected faith in favour of science, Lejeune defended their complementarity, stating, “How could there possibly be a contradiction between what is true and what is seen to be true? For it is always the second which arrives late.”

Lejeune’s significance can, perhaps, be best appreciated by comparing him with a contemporary who embodied the spirit of their age: Dr. John Rock. Like Lejeune, Rock was a Catholic doctor and father of five children. Rock attended daily Mass and insisted that he was guided by conscience in all that he did.[7] In 1931, Rock was the only Catholic physician to sign a petition requesting that Massachusetts legalize contraception, and as a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Harvard Medical School in the 1940s, he taught about contraception and co-authored a book on contraceptive methods, entitled Voluntary Parenthood. By the time he began developing “the Pill” in the 1950s, Rock believed global population control was necessary.

Following approval of “the Pill” in 1960 by the FDA, Rock urged the Church to approve its use for Catholics, arguing that it was a natural form of birth regulation because it consisted of synthetic progesterone and only extended a woman’s infertile period, making it a logical continuation of the “rhythm method.” While the Church deliberated, Rock took a decisive stance, publishing his position in his 1963 book The Time Has Come: A Catholic Doctor’s Proposals to End the Battle over Birth Control.

Three points of comparison can be made between Rock and Lejeune which highlight their differences. Despite their apparent similarities, they differed in their approach to Magisterial teaching. Rock chose not to follow the Church’s teaching on contraception, even when it was authoritatively proclaimed in Pope Paul VI’s encyclical Humanae Vitae on July 25, 1968. Lejeune, on the other hand, held and lived his faith, using his professional training and international reputation to defend life and condemn modern medicine’s various assaults on life. In his own words, “Fertilization outside the body – making a child without making love – and abortion – the unmaking of a child – are incompatible with natural moral law in varying degrees.”

Rock and Lejeune also diverge in the treatment they received from society. Rock became a public icon in the 1960s. He was interviewed widely, appearing in Time magazine and on the cover of Newsweek. In sharp contrast, as detailed above, Lejeune became an outcast in society and the scientific community.

Finally, these two men differed in the practice of their faith and the ends of their lives. Following the Church’s indictment of his position, Rock gave up the practice of his faith. In his later years, he ceased going to Mass and died away from the Church. In sharp contrast, Lejeune remained steadfast in his faith, becoming a close friend with a great saint and himself being considered for canonization.

In conclusion, Dr. Jérôme Lejeune was a strong and saintly man. At the forefront of his profession, he lived his faith integrally, weaving orthodoxy and orthopraxy seamlessly together in his life. He inspired others and used His God-given talents in the service of life, suffering for his defence of truth. He is thus a model for Catholics engaging with the evils of modernity, particularly the sustained assaults of the “Culture of Death.” Like Lejeune, Catholics must strive for excellence. They must pursue the truth and, once it is known, defend it without compromise, no matter the cost.

References

“Are You Afraid to Speak Against Abortion?” Culture of Life Studies Program, accessed November 15, 2019. https://cultureoflifestudies.com/blog/are-you-afraid-to-speak-against-abortion-a-lesson-from-dr-jerome-lejeune/#.Xc626VdKjIV.

“Biography.” Association les Amis du Professeur Jerome Lejeune, accessed November 6, 2019.http://www.amislejeune.org/index.php/en/jerome-lejeune/jerome-lejeunes-life/biography.

Curtis, Barbara. “The legacy of Dr. Jerome Lejeune.” Celebrate Life Magazine, July-August 2012 https://www.clmagazine.org/topic/pro-life-champions/the-legacy-of-dr-jerome-lejeune/.

“Cytogenetics.” Wikipedia, accessed November 15, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cytogenetics.

“Dates in the Life of Jérôme Lejeune.” Association les Amis du Professeur Jerome Lejeune, accessed November 6, 2019. http://www.amislejeune.org/index.php/en/jerome-lejeune/jerome-lejeunes-life/dates-in-the-life-of-jerome-lejeune.

“Declaration of the Servants of Life.” Association les Amis du Professeur Jerome Lejeune, accessed November 6, 2019. http://www.amislejeune.org/index.php/en/jerome-lejeune/jerome-lejeunes-message/textes-and-quotations/declaration-of-the-servants-of-life.

“Dr. John Rock (1890-1984)” American Experience, accessed November 9, 2019. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/pill-dr-john-rock-1890-1984/.

“Événements de mai 1968.” Larousse Encyclopedia, accessed November 7, 2019. https://www.larousse.fr/encyclopedie/divers/%c3%a9v%c3%a9nements_de_mai_1968/131140.

Havard, Alexandre. Virtuous Leadership. Strongsville, OH: Scepter Publishers, 2007.

“Jérôme Lejeune.” Jérôme Lejeune Foundation USA, 2017. https://lejeunefoundation.org/jerome-lejeune/.

“Jérôme Lejeune.” Wikipedia, accessed November 15, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J%C3%A9r%C3%B4me_Lejeune.

“Jérôme Lejeune: One of the greatest humanists of the 20th century.” Fondation Jérôme Lejeune, May 12, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=123&v=-3pIR6SJU7U

Quinones, Julian, and Arijeta Lajka. “What kind of Society do you want to live in?: Inside the country where Down Syndrome is disappearing.” CBS News, last modified August 15, 2017 https://www.cbsnews.com/news/down-syndrome-iceland/.

“Reputation for Sanctity.” Association les Amis du Professeur Jerome Lejeune, accessed November 6, 2019. http://www.amislejeune.org/index.php/en/the-cause-of-beatification/the-cause/how-does-a-cause-of-beatification-and-canonisation-work/reputation-for-sanctity.

“Sexual revolution.” Wikipedia, accessed November 9, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sexual_revolution.

“The civil rights movement: Social changes.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, accessed November 9, https://www.britannica.com/place/United-States/The-civil-rights-movement#ref613244.

Weigel, George. Witness to Hope: The Biography of John Paul II. New York: HarperCollins, 2001.

“Who was Professor Jérôme Lejeune?” Fondation Jérôme Lejeune, accessed November 6, 2019. https://www.fondationlejeune.org/en/the-foundation/jerome-lejeune/who-was-professor-jerome-lejeune/.

Wolin, Richard. “Events of May 1968.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, accessed November 7, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/event/events-of-May-1968/Aftermath-and-influence.

Endnotes

[1] The William Allen Award is the most prestigious honour in the field of genetics, awarded annually by the American Society of Human Genetics.

[2] Significantly, Lejeune was born on the Feast of St. Anthony of Padua – Lejeune would eventually find the chromosomal cause of Down Syndrome.

[3] Down Syndrome receives its name from Dr. John Langdon Down, a British physician who first recorded the condition’s physiological symptoms in the mid-1800s.

[4] Interestingly, Lejeune’s discovery came only two years after confirmation that humans possessed forty-six chromosomes.

[5] Previously, Down Syndrome had been attributed to maternal syphilis.

[6] Cytogenetics is a branch of genetics studying the relationship between chromosomes and cellular behaviour, particularly in cellular reproduction (mitosis and meiosis).

[7] Rock attributed this to his childhood pastor, who exhorted him, “John, always stick to your conscience. Never let anyone keep it for you.”