Much has been written about the physical and psychological effects of the crucifixion of Jesus, often by surgeons, psychiatrists, and other doctors. While well-intentioned, the writings have largely been inaccurate by forensic standards and until now have relied on educated speculation and outdated medical and other investigative equipment. The most famous work is the book A Doctor at Calvary, written by Pierre Barbet, M.D. His work has been widely quoted and generally held to be the benchmark study.

In 1988, Frederick T. Zugibe, M.D., Ph.D., wrote his first book on the crucifixion: The Cross and the Shroud. Since then, he has conducted more extensive experiments using the latest forensic methods. At the same time, the amount of research conducted by others into Jesus’ crucifixion has increased and there is now a large body of up-to-date findings from which to draw.

Dr. Zugibe is an expert in forensic pathology and was the Chief Medical Officer of Rockwood County, New York, from 1969 to 2003. He is an Adjunct Associate Professor at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. For the past twenty years, he has been the President of the Association of Scientists and Scholars International for the Shroud of Turin.

His interest in the forensic analysis of Jesus’ crucifixion began in 1948 when, as an undergraduate student of biology, he was critical of an article that appeared in the Catholic Medical Guardian. The article, “The Physical Cause of the Death of Our Lord,” by J. R. Whitaker, launched his lifelong study of the scientific and medical aspects of Jesus’ death.

“Forensic pathology—which requires many years of specialized education, training, and experience—is the medical speciality that deals with the mechanism and cause of suffering and death due to violence such as crucifixion. The forensic pathologist is a medical sleuth, an expert in reconstruction whose court testimony must possess a high degree of medical certainty. Indeed, his testimony may help to free an innocent defendant or release a killer back into the community.”1

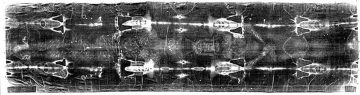

A study of Jesus’ crucifixion begins in the Garden of Gethsemane where Jesus prayed after the Last Supper. Then we follow Him as He is scourged at the hands of the Roman soldiers and made to stagger in the heat through the streets to Calvary. We then examine the effects of being nailed to and suspended on a cross until death. Regardless of the controversy surrounding the authenticity of the Shroud of Turin, it contains a wealth of information and must be included in a study of the crucifixion.

Carl Heinrich Bloch (1834-1890), Christ at Gethsemane: oil on canvas, public collection.

The Garden of Gethsemane

There is a rare condition called hematidrosis that may occur in cases of extreme anxiety caused by fear. Also known as hemorrhagia percutem, it manifests as sweat that contains blood or blood pigments.

Anxiety due to intense fear affects the autonomic nervous system. Fear triggers the amygdala, which is the brain’s fear centre. We know the reaction as the fight-or-flight response. The response results in the following: profuse sweating (diaphoresis), accelerated heart rate, vasoconstriction of blood vessels, increased blood pressure, diversion of blood from non-essential areas in order to increase blood perfusion to the brain and muscles of the arms and legs, skin pallor, and decreased function of the digestive system, which may result in vomiting and abdominal cramps.

Jesus’ fight-or-flight response lasted several hours as He prayed alone while His apostles slept nearby. He would have been completely exhausted and dehydrated because of diaphoresis and vomiting.

When the angel appeared to give Him strength, He would have had a sudden and complete reverse reaction, resulting in “severe dilation and rupture of the blood vessels into the sweat glands, causing hemorrhage into the ducts of the sweat glands and the subsequent extrusion out onto the skin.”2

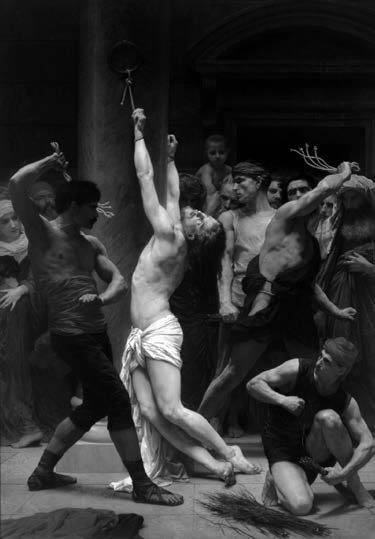

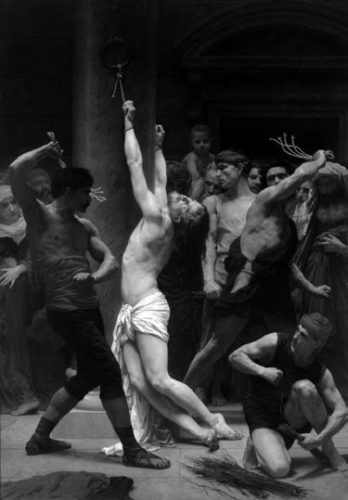

Jesus is scourged

“The Roman flagellation or scourging was one of the most feared of all punishments. It was a form of brutal, inhumane punishment generally executed by Roman soldiers using the most dreaded instrument of the time, called a flagrum.”3

The flagrum used in scourging was a whip consisting of three or more leather tails that had plumbatae, small metal balls or sheep bones at the end of each tail. As indicated on the Shroud of Turin, the flagrum used on Jesus had dumbbell-shaped plumbatae.

In Mosaic Law, scourging could not exceed forty lashes, but often the number of lashes was dependent upon the cruelty of the executioners. If the executioners did not want the cruciaris, or victim, to die too quickly, they limited the amount of lashes administered. The number of lashes also depended on the person and their crime.

Pilate ordered that Jesus be scourged in an extreme manner in an attempt to appease the mob. When they were not satisfied and demanded the release of Barabbas, he pronounced sentence.

Jesus would have been stripped naked and shackled by His wrists to a low column so that He would be in a bent-over position.

One or more soldiers would be assigned to deliver the blows from the flagrum. Standing beside the victim, he would strike in an arc-like fashion across the exposed back. “The weight of the metal or bone objects at the ends of the leather thongs would carry them to the front of the body as well as to the back and arms, the shoulders, arms, and legs down to and including the calves. The bits of metal would dig deep into the flesh, ripping small blood vessels, nerves, muscle, and skin.”4 The soldier would change position periodically and deliver blows from the opposite side.

William Adolphe Bouguereau, Flagellation de Notre Seigneur Jesus Christ, 1880: oil on canvas, Cathedral of La Rochelle, France.

Effects of scourging

The injuries sustained during scourging were extensive. Blows to the upper back and rib area caused rib fractures, severe bruising in the lungs, bleeding into the chest cavity and partial or complete pneumothorax (puncture wound to the lung causing it to collapse). As much as 125 millilitres of blood could be lost. The victim would periodically vomit, experience tremors and seizures, and have bouts of fainting. Each excruciating strike would elicit shrieks of pain. The victim would be diaphoretic (profusely sweating) and exhausted, his flesh mangled and ripped, and would crave water because of the loss of fluid from bleeding and diaphoresis. The steady loss of fluid would initiate hypovolemic shock while a slow, steady accumulation of fluid in the injured lungs (pleural effusion) would make breathing difficult. Fractured ribs would make breathing painful and the victim would only be able to take short, shallow breaths. The plumbatae at the end of the leather strips would lacerate the liver and maybe the spleen.

Jesus’ condition after scourging was serious. The pain and brutality of the torture put Him in early traumatic or injury shock. He was also in early hypovolemic shock because of pleural effusion, hematidrosis, hemorrhaging from His wounds, vomiting, and diaphoresis.

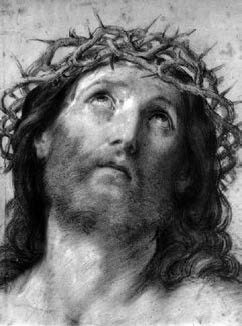

The crown of thorns

Dr. Michael Evanari, Professor of Botany at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, has opined that the Syrian Christ Thorn, which was available in Jerusalem, was the plant most likely to be used for the crown of thorns. Other experts speculate that the Christ’s Thorn was used, although no one can be certain that it grew in Jerusalem at the time of Jesus. Both of these plants have sharp, closely spaced thorns and can be easily plaited into a cap. The crown was not a wreath as is typically believed. It was a cap of thorns placed upon Jesus’ head. The pattern of blood flow in the head area on the shroud and subsequent experiments by Zugibe attest to this. “The shroud indicates areas of seepage and blood flow running down the forehead. The hair in the frontal image suggests marked saturation with dried blood, causing the hair to remain on both sides of the face.”5

Guido Reni, Ecce Homo, c. 1639: oil on canvas, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Italy.

Effects of the crown of thorns

“The nerve supply for pain perception to the head region is distributed by branches of two major nerves: the trigeminal nerve, which essentially supplies the front half of the head, and the greater occipital branch, which supplies the back half of the head.” 6 These two nerves enervate all areas of the head and face.

The trigeminal nerve, also known as the fifth cranial nerve, runs through the face, eyes, nose, mouth, and jaws. Irritation of this nerve by the crown of thorns would have caused a condition called trigeminal neuralgia or tic douloureux. This condition causes severe facial pain that may be triggered by light touch, swallowing, eating, talking, temperature changes, and exposure to wind. Stabbing pain radiates around the eyes, over the forehead, the upper lip, nose, cheek, the side of the tongue and the lower lip. Spasmodic episodes of stabbing, lancinating, and explosive pain are often more agonizing during times of fatigue or tension. It is said to be the worst pain that anyone can experience.

As the soldiers struck Jesus on His head with reeds, He would have felt excruciating pains across His face and deep into His ears, much like sensations from a hot poker or electric shock. These pains would have been felt all the way to Calvary and while on the Cross. As He walked and fell, as He was pushed and shoved, as He moved any part of His face, and as the slightest breeze touched His face, new waves of intense pain would have been triggered. The pain would have intensified His state of traumatic shock.

The thorns would have cut into the large supply of blood vessels in the head area. Jesus would have bled profusely, contributing to increasing hypovolemic shock.

He would have been growing increasingly weak and light-headed. As well, He would have bouts of vomiting, shortness of breath, and unsteadiness as hypovolemic and traumatic shock intensified.

The cross and the nails

How could a humiliated, weakened, beaten, bleeding, mangled mess of a man already suffering from breathing difficulties, as well as hypovolemic and traumatic shock, carry a t-shaped cross that weighed between 175 and 200 pounds? The short answer is that He did not.

The cross used in Roman crucifixions consisted of two parts: “the upright or mortise, referred to as the stipes, or staticulum, and the tenon or crosspiece, which is called the patibulum or antenna.”7 Historic information shows that the stipes were already in position at Calvary. Jesus carried the crosspiece. At Calvary He was nailed to the crosspiece, which was then placed into a rectangular notch carved into the tip of the stipes.

Did Jesus carry the crosspiece over one shoulder or over both shoulders? Sindologists (individuals who study the Shroud of Turin) interpret two images on the back of the shroud as evidence He carried the cross over both shoulders as it was tied to His wrists.

We know that Jesus fell at least three times on the way to Calvary. His condition was serious. Each time He fell, it would have been more difficult to get up. His executioners needed to keep Him alive until the crucifixion and so made Simon of Cyrene help carry the crosspiece.

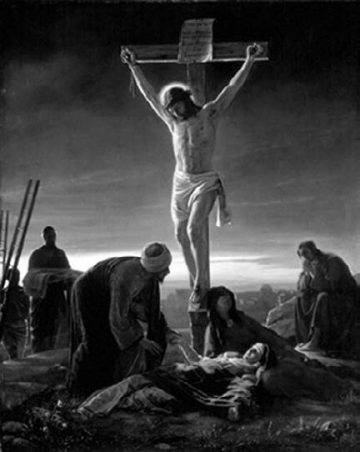

Carl Heinrich Bloch (1834-1890), The Crucifixion: oil on canvas, public collection.

The crucifixion

As a form of capital punishment, crucifixion was widespread prior to Jesus’ birth. It was abolished by Emperor Constantine in 341 AD but continued to be used by both Christians and non-Christians. More recently, Jews were crucified in the Dachau Concentration Camp. In Sudan and Egypt, there are reports of Christians being crucified by Muslim extremists.

Teams of well-trained Roman soldiers carried out the crucifixions. Each team consisted of the exactor mortis or centurion, and four soldiers called the quaternio.

Crucifixions were carried out in full view outside the city walls of Jerusalem in a hilly region called Calvary or Golgotha. “Roman crosses probably stood about seven to seven-and-a-half feet in height because from a practical point of view, it was easier to lift the crosspiece and victim into position on a shorter cross. It was also easier to remove the victim from a short cross after death. Shorter crosses also made it easier for wild animals to finish off victims.”8

In many artists’ interpretations, there is a suppadenum or support placed under Jesus’ feet. Historically, they are not mentioned in the writings or depicted in illustrations of crucifixions in Jesus’ time.

The nails used in crucifixion were made of iron. A typical nail used in Jesus’ time measured 12.5 centimetres long with a square shaft that measured 9 millimetres at the head and tapered off to a 5 millimetre point at the tip.

What happened at Calvary?

By the time He arrived at Calvary, Jesus was in exquisite pain, struggling to breathe and suffering from blood and fluid loss. One of the executioners threw Him to the ground and then made Him lie on His back. One other executioner pressed down on His chest, another held Him down by His legs, while a third soldier stretched His arms one at a time across the patibulum and nailed down His hands.

The pain from the nails would have been like having hot pokers driven through His hands, causing bolts of radiating pain up His arm. He would have screamed out in agony. “The process was repeated for the other hand, offering no relief from the agonizing pain. Then, two members of the execution squad likely manned the ends of the crosspiece while a third member grasped Jesus around the waist, getting Him to His feet. They backed Him up to the upright onto a platform device, and then two men lifted Him by the legs and inserted the crosspiece into a mortice on the top of the upright. They then bent His knees until His feet were flush to the cross and nailed His feet to the upright. Again, Jesus would likely have screamed out in agony after each foot was nailed.”9

Were the nails driven through Jesus’ palms or His wrists? In the book A Doctor at Calvary, Dr. Pierre Barbet determined that “the nails in the hands were driven into a natural space, generally known as Destot’s space, which is situated between the two rows of the bones of the wrist.”10 Barbet claimed that Destot’s space is in the wrist. However, Zugibe, who holds a Ph.D. in human anatomy and teaches gross anatomy to medical students, observed that Barbet’s diagram of the wrist and palmar surface of the hand contained mistakes. In addition, Barbet wrote that “the trunk of the median nerve is always seriously injured by the nail”11 but Zugibe points out that the median nerve is not located in the area that Barbet mentions.

Conducting a series of carefully designed experiments on live volunteers, Zugibe determined that the nails were hammered through Jesus’ palms, in the thenar furrow. When the nail is hammered here, the exit wound on the other side of the hand matches the wound image on the shroud. Stigmatics including Francis of Assisi, Catherine of Siena, and Padre Pio displayed wounds in the same spot.

Effects of nailing the hands

The median nerve runs through the thenar furrow where the nail was hammered. A nail through this area would cause a burning, searing pain so severe that the slightest touch, movement, or gentle breeze felt here is agonizing. This condition, known as causalgia, intensifies with an increase in temperature. If the pain is not abated with strong narcotics, the sufferer goes into traumatic shock. Raising and mounting the crosspiece to the top of the stipes would have triggered even greater pain and contributed to traumatic shock.

Nailing the feet to the stipes

The Romans bent the legs of their victims at the knees and then placed their feet flush against the cross. Then they hammered one nail through the top of each foot, severing the plantar nerves. The pain would have been similar to the causalgia caused by the palm injuries. In addition, the effect of bending the knees to align the feet against the stipes would cause cramping and numbness in the calves and thighs. This would force Jesus to arch His back in an attempt to straighten His legs and alleviate the cramping.

What was the cause of death?

The most notable theories about the cause of death are asphyxiation, heart attack or rupture, or shock. Until Zugibe’s book, there were no actual experiments to determine how Jesus died.

Zugibe’s volunteers who were positioned as accurately as possible to a replica of the Cross unanimously claimed that they had no difficulty breathing during expiration and inspiration. His findings, therefore, ruled out asphyxiation as a cause.

According to Zugibe, who is a previous Director of Cardiovascular Research with the US Veterans Administration, heart attack or rupture is an unlikely cause. Unless Jesus had a pre-existing heart condition (there is no mention of any prior illness in Scripture) the pain and suffering of scourging would not cause a heart attack. Even in the unlikely event that He did have a heart attack because of chest trauma, the passing of at least one full day after the fact would be necessary for the heart muscle to soften and rupture.

The most likely cause of death was traumatic and hypovolemic shock. This is supported by numerous experts on crucifixion, including Dr. William Edwards of the Mayo Clinic and Dr. P. F. Angelino and M. Abrata writing in the journal Sindon (1982).

How did blood and water flow from His side?

The chest wound markings on the shroud indicate that there was a pierced area in the right upper chamber of the heart (the right atrium). This heart chamber would have been filled with blood at the time of death. As well, Jesus would have pleural effusion (fluid around the lungs) as a result of the brutal scourging. When the spear was pulled out with a quick, jerky motion, it would have “carried out blood that had adhered to the blade and some of the pleural effusion from the pleural cavity, resulting in the phenomenon of ‘blood and water.’”12 After the spear was withdrawn, the lung would have collapsed, preventing any further seepage of watery fluid. There would not have been a great gush of blood or other fluids.

Jesus’ burial

Rigor mortis is a state in which all the muscles of the body stiffen and shorten. This happens as a result of an irreversible chemical reaction. It begins to set in about three hours after death, starting in the jaw and other facial muscles and progressing down the rest of the body. Shroud evidence shows that the rigor of the body had to be forcibly broken in order to be properly wrapped.

As per Jewish custom, the body was quickly washed. In the process, blood clots would have been dislodged. Any blood flow resulting from dislodging of the clots would have been considered unclean blood. In Jewish custom, unclean blood would not have been washed away.

The Shroud of Turin

Controversy about the authenticity of the shroud has persisted through many centuries. Numerous repairs and restorations that added different fibres and improper handling have contributed to the question of its validity.

Shroud scientists have requested additional advanced, random carbon dating samples. Turin authorities continue to refuse further testing, possibly because they believe the cloth to be sacred.

Pollen identification testing conducted on the shroud in 1973 and 1978 determined that most of the fifty-eight species of pollen on the shroud are found in the Jerusalem area. There are also traces of pollen from the Syrian Christ thorn on the cloth.

Even if the shroud were traced to the thirteenth century, as some have claimed is its century of origin, the question still remains of how the images came to be. All attempts to duplicate the image have failed. To draw accurate conclusions, scientists would need to experiment with a similarly injured cadaver shortly after death and would need to duplicate the conditions present within the tomb.

Conclusion

Speculation about how Jesus died continues to be of great interest. Numerous articles and books have been written on the subject. Many theories have been proposed and subsequently discarded.

Even if the exact circumstances and cause of death are never determined, what is clear is that our Lord suffered tremendously for many hours and then died an ignominious, lonely, excruciating death. We must remember that He did this willingly, mercifully, in atonement for our sins, and out of unfathomable love for us. In any study of Jesus’ crucifixion, that is the most important, undisputed fact.

- Frederick T. Zugibe, The Cross and the Shroud (New York: M. Evans and Company, Inc., 2005) 3.

- Ibid., 15.

- Ibid., 19.

- Ibid., 20.

- Ibid., 36.

- Ibid., 33.

- Ibid., 40.

- Ibid., 57.

- Ibid., 66.

- Pierre Barbet, A Doctor at Calvary (Garden City: Image Books, 1963) 119.

- Ibid., 110.

- Frederick T. Zugibe, The Cross and the Shroud (New York: M. Evans and Company, Inc., 2005).

Bibliography