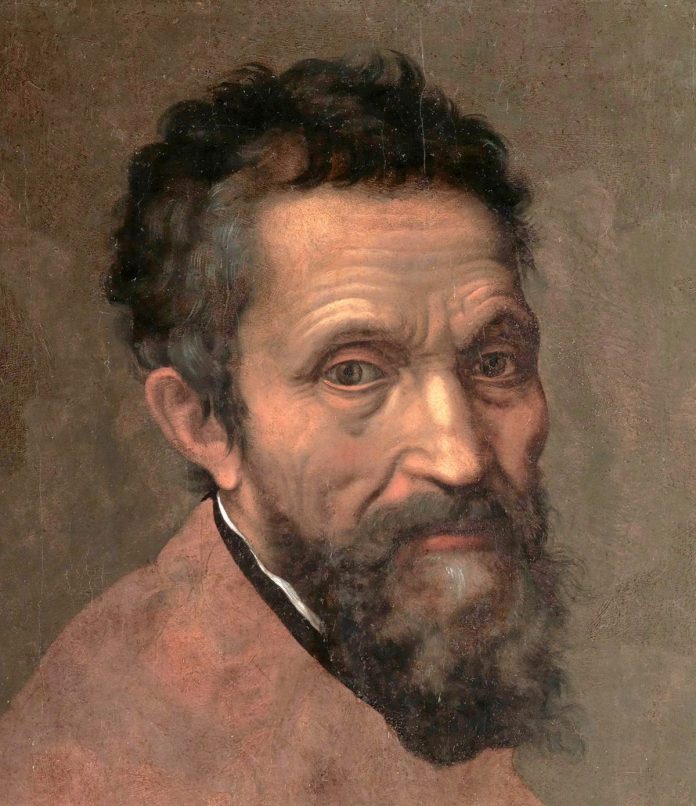

The Italian sculptor and painter Michelangelo lived to be nearly ninety years old, fulfilling his own dictum: I am a poor man and of little worth, who is laboring in that art that God has given me in order to extend my life as long as possible. That in his own opinion he was of little worth is difficult to understand when we look closely at the marvelous creative output of his life glorifying the heroes of the Old and New Testaments.

In the Sistine Chapel on the north wall the superb fresco of his Last Judgment alone took seven years. His amazing sculptures, Pietà and David, were completed before he was thirty. Because of many interruptions, the adornment of the tomb of Pope Julius II, with its great centerpiece of Moses, required forty years to complete. Upon completion of the Moses, the sculptor himself was so impressed that he struck one knee of Moses with a hammer and shouted, “Why don’t you speak to me?” His dedication to work even produced a radical change in his appearance. As he comments on himself: After four tortured years, more than 400 over life-sized figures, I felt as old and as weary as Jeremiah. I was only 37, yet friends did not recognize the old man I had become

Michelangelo grew up in the city of Florence, and after the death of his mother went to live with a stone cutter’s family where, no doubt, he learned to chisel, which may have fed his later preference for sculpture over painting. At the age of fourteen he was tutored both in sculpture and painting by the best craftsmen of Florence and was lured to apprenticeship in the court of Lorenzo de Medici, the powerful ruler of Florence. Because this was a period of revival of interest in ancient pagan art and statuary, the young student acquired early on a reverence for beauty of the type called terrible, awe-inspiring, large-than-life. At the age of seventeen he was dissecting cadavers, which reputedly enhanced his extraordinary ability to render the human anatomy both in sculpture and painting.

About this time he was probably influenced by the humanist philosopher Pico della Mirandola and the poet Angelo Poliziano. Michelangelo’s poetry, the least well-known of his arts, shows him to be centuries ahead of his time. He greatly admired Dante and Petrarch, and three centuries later might have been a welcome member of that romantic tribe — Byron, Keats, and Shelley — as the following lines suggest: (translated by John Frederick Nims)

Brow burning, in cool gloom as sundown shears

Earth of its gala rays, alone I’ve lain.

Others lie here in pleasure, I in pain,

Shaken, face down on earth, with sobs and tears.

When the fiery monk Savonarola, no great patron of the arts, took control of the city of Florence, Michelangelo moved to Rome. At the age of twenty-four he sculpted the Pietà, about which his student and biographer Giorgio Vasari commented, It is certainly a miracle that a formless block of stone could ever have been reduced to a perfection that nature is scarcely able to create in the flesh.

After Savonarola was burned at the stake, Michelangelo returned to Florence and created the enormous statue of David –which won him fame and the respect of his peers — and then painted Madonna and Child with John the Baptist. Perhaps on the strength of these two achievements, at the age of thirty he was invited to Rome to adorn the tomb of the new pope, Julius II. He was commissioned to cover the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel with a painting of the Twelve Apostles, but he persuaded the commissioners to let him try a more epic theme, the Creation and the history of the world from Adam and Eve through the Great Flood to the coming of Christ.

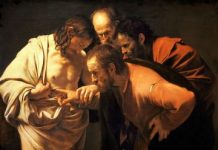

Twenty-two years after the painting of the Creation, Michelangelo commenced work on the Last Judgment, a majestic rendition of Christ’s Second Coming and the judgment of all the saints and sinners. The martyred Saint Bartholomew is pictured holding in his hand the flayed and wrinkled skin of his own face, the face of Michelangelo. But the abounding nude figures and bare genitals caused quite a fuss. If not for the pope, the genitals would have been covered up; indeed, after the pope’s death, Daniele da Volterra, one of Michelangelo’s apprentices, did cover them. Michelangelo’s last great accomplishment in old age was to design the dome of the reconstructed St. Peter’s Cathedral. He lived to see the drum completed, but not the magnificent dome.

What was Michelangelo the man like? He was regarded by many of his contemporaries as a loner who lived in monk-like chastity and austerity, and was arrogant and rough in his relations with others. Possibly he had listened too well to some of Savonarola’s sermons, in that he dressed poorly and ate little. He could be envious, as when he was infuriated by Da Vinci’s claim that painting was superior to sculpture. They were challenged to a painter’s duel that neither was able to finish.

But there was a tender side to Michelangelo in the fact that he spent himself encouraging the talent of younger artists. He slaved away, especially for four popes, and complained constantly of his treatment by them; yet there can be no doubt that in the end he perceived them as the istruments by which he had been lifted up to glorify God’s creation. There could be a childlike innocence and simplicity about him. He was tricked by an art dealer into making a statue of Cupid that would look like a relic of pagan antiquity. The dealer paid Michelangelo only thirty ducats, then turned a handsome profit by selling the statue as a pagan antique for 200 ducats. There is the apocryphal story of the great artist, so adamant about insisting that he work in private, that he hurled planks from the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel at Pope Julius when he would sneak into the chapel at night to observe Michelagelo’s progress on the Creation.

A constant bachelor, we do not know much about Michelangelo’s love life. Being childless, he was attracted to younger men and wrote tender poems to them, but it’s feasible that these attractions were not so much sexual as fatherly.

Michelangelo was certainly the towering artistic genius of his day. Some would say that in painting he was equalled or excelled by Raphael and Da Vinci, but the sheer quantity and size of his creations in all the art forms of his day – sculpture, painting, architecture, and poetry — secured for him the enviable title that certainly no modern can claim … the Renaissance Man. He strove for perfection, and even beyond. In his old age he destroyed his preliminary sketches for his major works, lest anyone should see how imperfectly he had struggled toward the ideal. Yet those sketches that survived show a degree of perfection that any other artist might have died to achieve.

Benedetto Varchi, a historian, read the funeral oration for Michelangelo. The words he had to say would be ageless words for an ageless hero of the arts.

This is a phenomenon so new, so unusual, so unheard of in all times, in all history that … I am not only full of admiration, not only amazed, not only astonished and startled and one reborn – but my pulse flutters, my blood runs cold, my mind reels, and my hair stands on end, so moved am I by … trepidations.

From the Pen of Michelangelo

“Genius is eternal patience.”

“I live and love in God’s peculiar light.”

“Good painting is the kind that looks like sculpture.”

“Lord, grant that I may always desire more than I can accomplish.”

“I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.”

“If people knew how hard I had to work to gain my mastery, it wouldn’t seem wonderful at all.”

“If we have been pleased with life, we should not be displeased with death, since it comes from the hand of the same master.”

“A man paints with his brains and not with his hands.”

“Beauty is the purgation of superfluities.”

“Death and love are the two wings that bear the good man to heaven.”