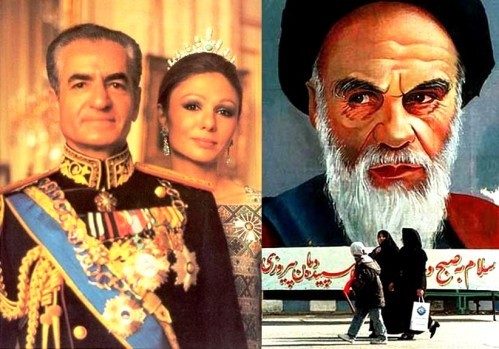

“What did I do to them?” Shah Reza Pahlavi, 1979

Throughout the world, February 11 of this year may have seemed like any other day.

Throughout the world, February 11 of this year may have seemed like any other day.

It wasn’t.

On that day, Iranians took to the streets nationwide to mark the 40th anniversary of the Islamic Revolution which began in the early days of 1979 with the toppling of Mohammad Rez Shah Pahlavi from the Peacock throne and ending Iran’s 2,500-year-old monarchy. The revolution then continued under the rule of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini who, after returning from 14 years in exile, became the first supreme leader of the Islamic Republic—an oppressive, anti-Western theocracy—until his death in 1989.

It was also the feast day of Our Lady of Lourdes, celebrated as quietly by Iran’s 21,380 Catholics this year as it was 40 years ago when their religious status shifted to dhimmitude under Islamic sharia and the picture of the Ayatollah began appearing on the cover of their catechisms.

Central to this year’s celebrations was the government’s bold unveiling of a new surface-to-surface missile with a range of 1,300 kilometres — close enough to strike one of Iran’s main enemies, Israel, and in defiance of U.S. policy, though Tehran insists their programme is purely defensive.

Also unchanged was Iran’s 40-year-old mantra “Death to America” which is still heard on public occasions.

“As long as America continues its wickedness, the Iranian nation will not abandon ‘Death to America,’” proclaimed the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, according to Reuters. Which this year meant death to named American rulers such as President Trump, National Security adviser John Bolton and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo.

Iranian malaise

Even so, this parade of strength and bombast could not conceal the ongoing distress of the Iranian people who, according to news analyst Fatma Lofti of Daily News Egypt, have suffered four decades of Islamic rule so devastating that their demand for an overthrow of the regime is ongoing and well known around the world.

Their current situation has also prompted many to ask what really happened to Iran, and scholars to reassess the real legacy of the Shah who, in the flux of revolution, was widely denounced as a corrupt and brutal dictator who championed Western reforms while transforming Iran into a modern, prosperous and powerful state. Was he really the monster depicted? How did this shah — who in the space of a few decades transformed his poverty-stricken country into southwestern Asia’s most powerful state and the world’s second-largest oil producer — come to be so loathed?

“What did I do to them?” he wondered out loud to his wife, Farah Diba. But, as he found himself in a hopeless position and forced to flee his own land, neither would he consider forcing himself on subjects who didn’t want him.

And now, forty years on, Iranians are asking themselves, if revolution was the answer, why the wave of militant unrest unleashed by the Islamic Revolution four decades ago is still roiling the entire Middle East? And why the revolution reversed Iran’s fortunes so spectacularly despite its early promises that it would deliver political and economic freedom rather than the harsh Islamic rules, weak economy and government corruption it did. Their national misery was further compounded by the eight-year Iran-Iraq war which began in September 1980 when Iraq, under Saddam Hussein, invaded Iran. It ended in August 1988, when Iran accepted a UN-brokered ceasefire.

“Iran has been devastated by 40 years of the Islamic Republic’s rule. Its environment has been severely damaged and its economy is near collapse,” Alireza Nader, of the New Iran research group, told the Daily News Egypt (DNE) last month. “No wonder that more and more Iranians are demanding a complete overthrow of the regime.”

But Nader’s assessment doesn’t mean that the current regime in Iran is anywhere near a brink.

“It is not near collapse like many US policymakers claim,” Dina Esfandiary, a fellow at the Belfer Centre for Science and International Affairs at Harvard’s John F.Kennedy School, told DNE. “Rather it is a very different Islamic Republic than the one present 40 years ago. Tehran’s foreign policy is no longer about exporting the revolution, but rather a relatively pragmatic one designed to ensure its security and the safety of its borders.”

The safety of its borders. Did the globalists hear that?

Carter and Brzezinski

One might ask what exactly U.S. president Jimmy Carter and his adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski were thinking when they seemed to ensure the fall of the Shah in myriad ways. Not only did this feckless pair ignore the Shah’s troubles in November 1978 as tens of thousands of students were demonstrating across Iran, they also withdrew an earlier offer of asylum in January 1979 when he was so ill and fleeing. “The offer was withdrawn apparently in the belief that establishing good relations with the new rulers of Iran took precedence over granting asylum to the Shah and his family,” reports historian Bernard Lewis in The Crisis in Islam.

One might ask what exactly U.S. president Jimmy Carter and his adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski were thinking when they seemed to ensure the fall of the Shah in myriad ways. Not only did this feckless pair ignore the Shah’s troubles in November 1978 as tens of thousands of students were demonstrating across Iran, they also withdrew an earlier offer of asylum in January 1979 when he was so ill and fleeing. “The offer was withdrawn apparently in the belief that establishing good relations with the new rulers of Iran took precedence over granting asylum to the Shah and his family,” reports historian Bernard Lewis in The Crisis in Islam.

In retrospect such consequences seem typical of Carter who, in those days, was avidly promoting an American foreign policy based on what historian Paul Johnson has called an “ill-considered” human rights policy by which Carter sought to end violations of human rights throughout the world, all the while producing one disastrous result after another, including in Iran: “The Shah’s state road to Utopia led only to Golgotha,” Johnson concluded.

And as the Middle East became increasingly destabilized after the fall of Iran, it became increasingly obvious as well that the dechristianization and secularization of the West was also playing a huge, perhaps even primary, role in this latest rise and advance of Islam. And its viability in the modern world was confirmed by no less than Ayatollah Khomeini in 1984:

“If one allows the infidels to continue playing the role of corrupters on Earth, their eventual moral punishment will be all the stronger. Thus if we kill the infidels in order to put a stop to their (corrupting) activities, we have indeed done them a service. For their eventual punishment will be less. To allow the infidels to stay alive means to let them do more corrupting.”

A striking comment, is it not, on what Pope John Paul II so aptly described as the West’s Culture of Death? And was it not a further irony that John Paul II ascended to the papacy during precisely the same period when Iran was falling?

Regardless, such huge shifts in power only made Brzezinski’s assurance to Carter in 1979 seem all the more fatuous: “We should be careful not to over-generalize from the Iranian case. Islamic revivalist movements are not sweeping the Middle East and are not likely to be the wave of the future.”

Hilaire Belloc’s predictions

Which brings us to Hilaire Belloc’s prognostications on the future of Islam in the 1930’s which turned out to be particularly astute. At the time of his writing, Britain was under threat from Nazism and the Islamic world was still largely under the rule of the European colonial powers after the formal dissolution of the 600-year reign of the Ottoman Empire in 1923. But the Catholic historian considered even then that Islam was intent on destroying the Christian faith, as well as the West, which Christendom had built. And that it was simply a matter of time and events that would one day see its re-emergence from its state of hibernation during the 1930s.

Which brings us to Hilaire Belloc’s prognostications on the future of Islam in the 1930’s which turned out to be particularly astute. At the time of his writing, Britain was under threat from Nazism and the Islamic world was still largely under the rule of the European colonial powers after the formal dissolution of the 600-year reign of the Ottoman Empire in 1923. But the Catholic historian considered even then that Islam was intent on destroying the Christian faith, as well as the West, which Christendom had built. And that it was simply a matter of time and events that would one day see its re-emergence from its state of hibernation during the 1930s.

Indeed, as early as 1937, Belloc foresaw Islam’s capacity to reverse its then-current diminution as a geopolitical force: “Perhaps that change will be deferred, but change there will be, continuous and great. Nor does it seem probable that at the end of such a change, especially if the process be prolonged, Islam will be the loser.”

Islam will not lose, Belloc reasoned, because it had not suffered the West’s spiritual decline.

“It has always seemed to me possible, and even probable,” Belloc wrote in 1938, “that there would be a resurrection of Islam and that our sons or our grandsons would see the renewal of that tremendous struggle between the Christian culture and what has been for more than a thousand years its greatest opponent.”

In his 1938 book The Great Heresies, Belloc devoted an entire chapter to Islam, which he titled “The Great and Enduring Heresy of Mohammed,” in which he predicted the reemergence of Islam as a global force and unparalleled foe of Christian civilization, and that all Islam needed to reemerge as a dangerous global power was a cause or leader to unite its scattered masses in global jihad.

“Now it is probable enough that on these lines—unity under a leader—the return of Islam may arrive,” Belloc concluded. “There is no leader as yet, but enthusiasm might bring one and there are signs enough in the political heavens today of what we may have to expect from the revolt of Islam at some future date—perhaps not far distant.”

What Belloc didn’t see — apart from the secularization of the West and its resulting moral corruption — was that other phenomenon that came to serve Islam: The rise of globalism in which powerbrokers across the West have long since involved themselves.

Advancing Islam

As did Khomeini who, according to British philosopher Roger Scruton, well understood its power and potential for advancing Islam. “For someone like Khomeini, human rights and secular government display the decadence of Western civilization, which has failed to arm itself against those who intend to destroy it and hopes to appease them instead. The message is that there can be no compromise, and systems that make compromise and conciliation into their ruling principles are merely aspects of the Devil’s work.”

Which is why Scruton regards Khomeini as a figure of great historical importance: “He showed that Islamic government is a viable option in the modern world, so destroying the belief that Westernization and secularization are inevitable.”

In Scruton’s view, globalization does not mean merely the expansion of communications, contacts, and trade around the globe. It means the transfer of social, economic, political, and judicial power to global organizations, by which he means organizations located in no particular sovereign jurisdiction and governed by no particular territorial law. Whether in the form of multinational corporations, international courts or transnational legislatures, these organizations pose a new kind of threat to the only form of sovereignty that has brought lasting (albeit local) peace to our world.

“And when terrorism too becomes globalized, the threat is amplified a hundred fold,” concludes Scruton, in his book The West and the Rest, noting that it is now Wall Street and Zurich providing its international finance and the latest technology providing its multinational outreach. “With al-Qa’eda, therefore, we encounter the real impact of globalization on the Islamic revival. To belong to this ‘base’ is to accept no territory as home, and no human law as authoritative. It is to commit oneself to a state of permanent exile, while at the same time resolving to carry out God’s work of punishment.”

In Scruton’s view, the growing globalization that so enthused Carter and Brzezinski, has brought into being a true Islamic umma, which identifies itself across borders in a global form of legitimacy, and which attaches itself to global institutions and techniques that are the by-products of Western democracy. “This new form of globalized Islam satisfies a hunger for membership that globalization itself has created,” he writes. “It calls on the old nostalgia of the muhajir, and directs it not at some local usurper but at God’s enemies, wherever they are.”

A thousand points of light

And all of which has been hugely facilitated by the late George H.W. Bush’s New World Order — along with its thousand-points-of-light — which he brought into official being on January 20, 1989 on his inauguration day as U.S. president.

And leaving as an open question — reminiscent of St.Paul’s warning about ‘Powers and Principalities’ and intensely appealing to conspiracy theorists as well — as to which, if any, of those global powers and principalities played a role in the demise of the Shah and the fomenting of civil wars in nearby nations such as Jordan and Lebanon, each in turn contributing to the high levels of migrancy the West has been absorbing for decades.

Should they be asking themselves: “How spontaneous was the Iranian Revolution, really?” And if not spontaneous but orchestrated, what then were its true goals?