Go forth without fear, for he who created you has made you holy, has always protected you, and loves you as a mother. —St. Clare of Assis

While some dioceses and parishes are handling the COVID19 crisis better than others when it comes to reaching the faithful through technology, the Church as a whole is succeeding because of a centuries-long foundation.

Though critics, including many of the faithful, often view the Catholic Church as antiquated and out of touch with the modern world, the Church throughout history has demonstrated a willingness to respond to, and embrace, emerging communication technology. Adopting modern digital communication tools continues that response and demonstrates the Church’s eternal relevance. This open-minded progress dates as far back as the second century when a young Catholic Church was communicating with trending, cutting-edge technology.

Until that time, the basic form of any book, defined as any written works or collections thereof, was the scroll. Though still used today in Judaism for the Torah, scrolls are mostly obsolete technology. Their slow decline began when the codex, pages of papyrus or animal skin bound together on one side like a modern book, emerged in the second century.

Though it did not become universal until the fourth century, the codex was adopted hundreds of years earlier by Christianity and the young Catholic Church. In fact, most Christian manuscripts from the second and third centuries were codices.[1] Perhaps, as with most advances in communication technology, the proliferation of the codex was a result of its ease of use.

This was only the beginning. History shows us continued progress in adoption, and the sanctification of, secular communication methods. Beyond the codices of the third century, the Church’s communication methods have been modern and forward-thinking. Catholic baptism of communication technology spans centuries and continues today. Here are a few highlights from the Catholic Church’s history of using mainstream media to convey the unique messages of the Church.

1792

During a time when print ruled mass communications, media and political pioneer, Fr. Gabriel Richard, came to the United States and brought the printing press to Detroit, Michigan. In 1802, Fr. Richard began publishing Michigan Essay and Impartial Observer in Detroit. It was the first Catholic newspaper published in the United States.[2] He went on to be elected the first Catholic priest in the United States Congress, serving one term from 1823 to 1825.[3]

1822

Two decades after Fr. Richard’s newspaper began circulating, the Most Reverend John England was the first bishop of Charleston, South Carolina. Well respected by Catholics and non-Catholics alike, Bishop England founded the United States Catholic Miscellany in another early adoption of communication technology: print, in this case.[4]

1927

“If you like a Catholic paper with snap, vigor, courage, here it is. If you like one that is easy to read, here it is. If you like one that will always be loyal to the Church and has no selfish axe to grind, here it is.” Msgr. Matthew Smith wrote these words in the inaugural issue of the National Catholic Register 90 years ago. Purchased by the Eternal Word Television Network (EWTN) in 2011, the Register is now largely Catholic newspaper distributed digitally and is read by “tens of thousands of active lay Catholics along with over 800 priests, 160 bishops, 40 archbishops and 30 Vatican officials” according to its content-rich website.[5]

1939

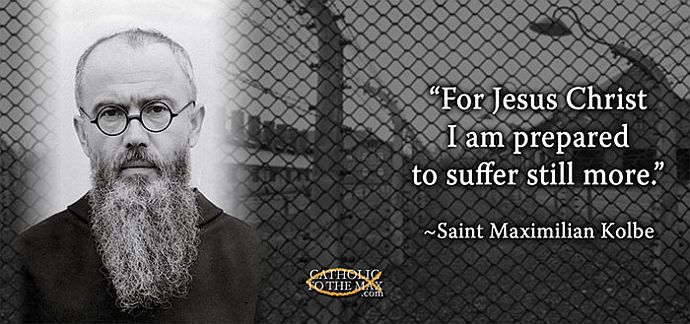

“If Jesus or St. Francis (of Assisi) were alive now, they’d use modern technology to reach the people.” These words of St. Maximilian Kolbe call from his remarkable time on earth to today’s Church, reminding us of its mission and how to carry out that mission.

Kolbe, known to most during his life as Fr. Maximilian, is most commonly remembered as the Franciscan priest who gave his life at Auschwitz so another man would live. Though his life ended in quiet martyrdom, he spent most of his earthly journey loudly, but gently, proclaiming the Gospel in the most effective ways he could. Speaking several languages including Russian, German, Italian, and Latin, in addition to his native Polish, Kolbe was, in every way, a communicator.

“No one can alter the truth,” Fr. Maximilian said in a 1940 article in his magazine, The Knight. “What we can do and should do is to search for the truth and then serve it when we have found it.” He served the truth by communicating it.

Before World War II, Fr. Maximilian’s Conventual Franciscan monastery at Niepokalanow in Poland had a daily newspaper and a radio station, in addition to The Knight, and was getting ready for television. As a servant leader, Fr. Maximilian worked tirelessly, and often covertly, with his fellow friars distributing the messages of the Church across the most modern of communication channels. He did not cease during the war, as he believed that was the time when communication of the truth was most vital. Fr. Maximilian believed Adolf Hitler’s philosophy to be the antithesis of everything Christ stood for, and he communicated that truth with precision, passion, and technology.[6]

1957

In his encyclical letter Miranda Prorsus, Pope Pius XII made a case for what he called “very remarkable technical inventions which … reach the mass of the people themselves.” The Holy Father was referring to the modern and emerging technology of the time: motion pictures, radio, and television. The ability of these technologies to reach the masses was of particular interest to the Pope because of the duty and mission of the Catholic Church.

“Hers (the Church’s) is the duty, and for a much stronger reason than all others can claim, of announcing a message to every man,” he wrote. “This is the message of eternal salvation; a message unrivalled in its richness and power, a message, in fine, which all men of every race and every age must accept and embrace.”[7]

1963

His Holiness Pope Paul VI promulgated the Vatican II decree Inter Mirifica, the decree on the media of social communications. The document acknowledged and praised the value and tremendous potential of communication technology of the time, specifically “press, movies, radio, television and the like,” in proclaiming the Gospel and supporting the Kingdom of God. In a bold statement and challenge to Church leaders, Inter Mirifica asserted the following:

It is … an inherent right of the Church to have at its disposal and to employ any of these media insofar as they are necessary or useful for the instruction of Christians and all its efforts for the welfare of souls. It is the duty of Pastors to instruct and guide the faithful so that they, with the help of these same media, may further the salvation and perfection of themselves and of the entire human family.[8]

1981

Could a cloistered 13th-century Franciscan nun have prophesized the use of television by the Church? St. Clare of Assisi, foundress of the Poor Clares, the first Franciscan nun, and the patron saint of television, might have done just that. Salt and Light Media’s Carolos Ferreira recounts Clare’s miraculous experience:

One Christmas Eve, Clare was so sick that she could not get out of bed even to go to Mass. While the other sisters were on their way to Mass, she stayed in bed praying so she could take part in the mass with her prayer. Just then, the Lord granted her a miraculous vision, and she was able to see the Mass, even though she was far away from where it was happening, as if it were taking place right in her own bedroom.[9]

Seven hundred years later a Franciscan nun, Mother Angelica, founded the Eternal Word Television Network (EWTN), the first Catholic satellite television in the United States. Broadcasting Holy Mass and Catholic programming to the masses along with her sisters, friars, and priests, Mother Angelica said, “Faith is what gets you started. Hope is what keeps you going. Love is what brings you to the end.”[10]

While Saint Clare of Assisi is the patroness of television and Saint Maximilian Kolbe is the patron of media communications, perhaps no one in modern Catholic history is better known as a progressive communicator as Karol Wojtyla: actor, singer, poet, writer, priest, pope, saint. He took the name John Paul II when he was elected to succeed the late Pope John Paul I in 1978.

While popes praised and endorsed emerging communication technology, no one before John Paul II used media quite like he did. Deemed “The People’s Pope” by biographer James Oram, John Paul II engaged with people through media long before his papacy. In 1950, the young Fr. Karol Wojtyla began writing for Tygodnik Powszechny, a Catholic newspaper in Poland. In the 1970s, Cardinal Wojtyla published journal articles on theology, philosophy, and sociology while continuing to write regularly for Tygodnik Powszechny and Znak, a monthly magazine.[11]

During a visit to the United States in 1976, Cardinal Wojtyla took immediate and particular notice of the country’s broadcast technology and freedom of the press. Two years later, on the heels of his Papal inauguration, Wojtyla said to an Associated Press reporter, in English, “I love America. I thank you, Associated Press.” Pope John Paul II built a relationship with journalists from that time through his papacy. He answered their questions in the language in which they were asked. He showed a great respect for journalistic communication.[12]

Pope John Paul II’s love for God, the Church, and the people was evident in every encounter, whether in person or via technology. He used communication tools to build personal relationships with the faithful. Biographer Tad Szulc describes Pope John Paul II, the great communicator:

The Polish pope is a man of touching kindness and deep personal warmth, a quality that evidently he communicates to the hundreds of millions of people who have seen him in person … or on satellite or local television. His smiling face is probably the best known in the world, John Paul II having elevated his mastery of modern communications technology in the service of his gospel to the state of the art.[13]

John Paul II often referred to himself as the “Pilgrim Pope.” His definition of “pilgrim” did not only include charting new frontiers geographically, but technologically. Pope John Paul II grasped the ability modern technology like television and computers offered him to reach huge masses of people in person. Pope, now Saint, John Paul II baptized modern communication technology, and used it to reach the people with the message of the gospel–a unique message—using standard secular tools.[14]

It is fitting that John Paul II’s Mass of Canonization was broadcast live on television and streamed live online.\

The positions of Church leaders on communication technology are not much different in the post-John-Paul-II 21st century. This might be because of the relatively low-profile Pope Benedict XVI (John Paul II’s successor) kept, with the exception of his endeavor as the first pope on Twitter. Or perhaps modern Church leaders see so much potential as communication technology continues to advance at a rapid pace.

The conclave that would elect Pope Francis in 2013 was concerned with the ability to get the message out using modern means of communication. Today’s Papal Office exists in an age of instantaneous communication. Social media and digital platforms dominate how we relate to each other and how the Church related to its people. Think about it … the Pope’s on Twitter. And Instagram. And the Vatican is on social media.

This is a result of the rich communication history of the Church. Right now, local parishes and religious orders are using technology like Facebook and Zoom to reach the people. Based on its past practices and willingness to embrace technological change, the Catholic Church may have been one of the most prepared organizations on the planet relating to dealing with today’s pandemic.

[1] Rev. Dr. Edward Foley, OFM Cap. From Age to Age. (Chicago: Liturgy Training Publications, 1991)

[2] “Catholic Newspapers.” Catholic History. catholichistory.net. 2007

[3] “Richard, Gabriel.” United States Congress. bioguide.congress.gov.

[4] “Catholic Newspapers.” Catholic History. catholichistory.net. 2007

[5] “About Us.” National Catholic Register. ncregister.com.

[6] Patricia Treece. A Man for Others: Maximilian Kolbe the ‘Saint of Auschwitz.’ (Libertyville, IL: Marytown Press, 1993.)

[7] Pope Pius XII. Miranda Prorsus. (Rome: Tipografia Poliglotta, 1957)

[8] Pope Paul VI. “Inter Mirifica.” The Holy See. vatican.va

[9] Carlos Ferreira. “Saint Clare of Assisi: Patroness of Television.” Salt and Light Catholic Media Foundation. saltandlighttv.org. 10 Aug 2012.

[10] “Beginning of EWTN.” EWTN Global Catholic Network. ewtn.com.

[11] James Oram. The People’s Pope: The Story of Karol Wojtlya of Poland. (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1979), 92

[12] James Oram. The People’s Pope: The Story of Karol Wojtlya of Poland. (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1979), 195, 196.

[13] Tad Szulc. Pope John Paul II: The Biography. (New York: Scribner, 1995), 24.

[14] Tad Szulc. Pope John Paul II: The Biography. (New York: Scribner, 1995), 338.