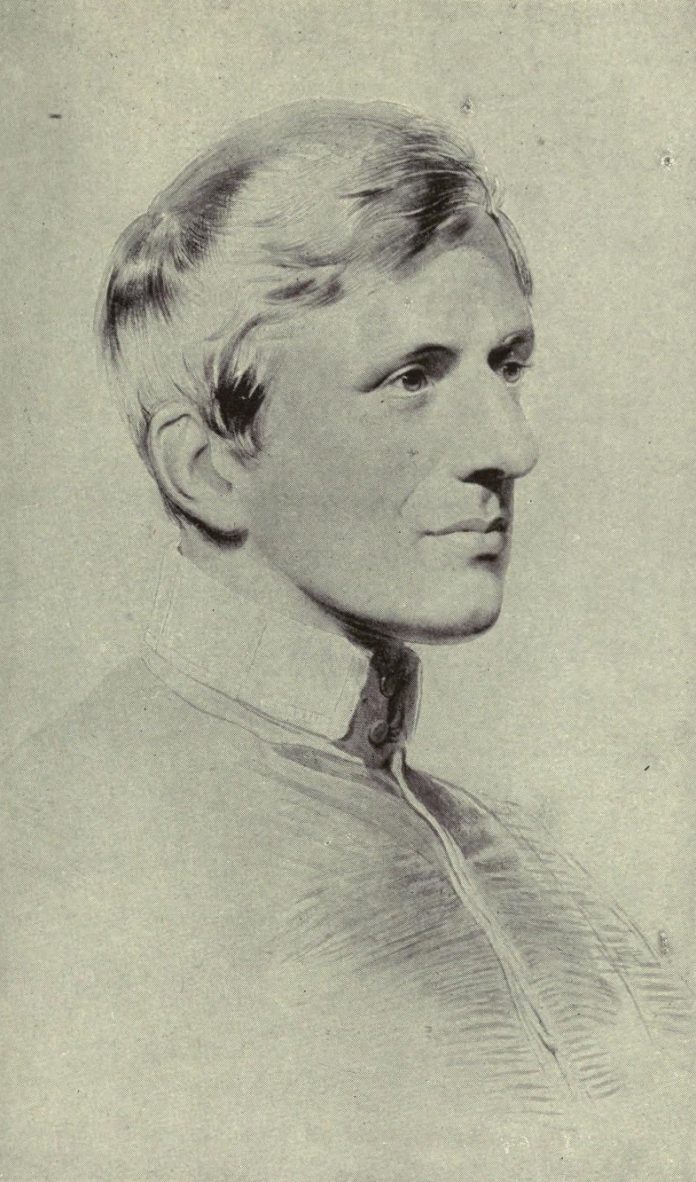

(This is the second article in a series on Newman’s philosophy of education. For the first reflection, may be found here).

Newman recognized that knowledge concerning morality cannot be deduced but should be induced, hence his preference for inductive learning. It could even be said that Newman relied upon assumptions not derived inductively, deductively, or through any a priori experience. These assumptions served as foundations for the propositions they supported. Newman suggested that discipleship begins when a person is persuaded by the rhetoric of Christ, whose virtuous life rendered his character’s authority unsurpassable, whose words and actions formed the best argument, and whose message was suited to his hearers to produce effective results. Newman attempted to harmonize the nuanced and subtle nature of conscience with the rigorous, scientific laws of moral theories.

Aristotle, who greatly influenced Newman’s understanding of knowledge, examined ideas in relation to their telos – their end or purpose. The proper telos of humanity, a central question in ancient ethics, was defined as the full development and perfection of the rational soul. Aristotle asserted that humans naturally desire to know, and that the nature of a thing is its end, meaning what each thing is when fully developed is its nature. However, Newman differed, asserting that ethics is not strictly a science, as it is not purely a branch of knowledge. Ethical principles cannot be deduced like material principles; establishing ethical principles requires practical experience.

For Newman, theology begins with wonder, and it was imperative to him that theology remained subservient to that which calls it forth and by which it is reciprocally possessed. Newman famously called theology the ‘Queen of the Sciences,’ as the classical trivium and quadrivium, preceding specialized study in law, and medicine, or the social and physical sciences of the modern university, had their basis in wonder. Aristotle locates wonder, the source and telos of classical study, as the first step to knowledge.

Newman implicitly continues this argument by linking theology, whose premise is wonder, with all other university subjects, as each contains an implicit reception and explicit statement; a given nature that, like revelation, prompts and requires gradual unfolding in understanding. The clear implication is that all sciences begin in wonder and develop into systematic reflections upon them through the operation of reason, serving those impressions held in faith, as indeed also in other sciences. Newman presents ancient Athens, where strangers from all lands gathered to pursue universal truth, as the original fount and ideal against which all other universities and education systems pale.

To Newman, the university is foremost a place for teaching universal knowledge, a place where the universe is taught and where a universality of people assembles to learn. Furthermore, to Newman, the collegiate environment was important as it was where individuals develop desirable traits through association, such as self-possession, courtesy, conversational skills, and the ability to not offend. These qualities, rather than acquired through reading and lectures, are the fruit of the collegiate system. Newman distinguishes between intellectual formation from reading and lectures and character formation developed through virtuous company in the university’s colleges and halls of residence. Newman followed St. Philip Neri, founder of the Oratory to which Newman belonged, as a model. Philip was a man of liberal culture on easy and equal terms with the rich and powerful, who had forfeited his riches and status to minister to the many as well as to the few.

Newman, as a contemporaneous opponent of modernism, locates miracles and the supernatural at the heart of education, rather than seeking to cleanse knowledge of the religious phenomenon. In the age of modernism, Newman defended belief in miracles, citing The Blessed Virgin Mary as the ‘pattern of faith,’ who first believed without reasoning, then from love and reverence, reasoned after believing. She symbolizes the faith of both the unlearned and the doctors of the Church. Newman believed that just as Mary pondered over what she had been told, the Church ‘ponders’ through theological thought, committing faith to the theologians and even the science of theology. Art, in contrast to scientific rationalism, offers the best vehicle for religious education. The artist senses the boundaries of art, and in the same way, the catechist attempts to transmit the meaning of truth and the mystery of faith.

Mystagogy is a process of leading or training into the mystery, specifically an initiation into God’s self-revelation. It is the sharing and interpreting religious experience, the mystery of faith, and celebrating the liturgy in common. The Christian faith is fundamentally social, requiring a community to experience and share that faith. Mystagogy links to inductive education, which this paper argues Newman supported. The pedagogical transformative capacity of the story resides within a transcendental and aesthetic philosophy of education, supported by Orthodox apocatastasis and sophism. Newman distinguishes between the university and the college, the one nurturing intellect and the other virtue. Newman preferred the Athenian model over the Roman, as the former does not systematize or constrain but is fertile in schools rather than military successes, open to the world and attracting people through its love of learning and philosophy.

Newman rejected viewing knowledge in terms of productivity and utility, arguing that the highest form of knowledge is ‘use-less’, but this is the very thing that makes it free to pursue the truth for its own sake, as befits a ‘liberal’ education. Aesthetics and ethics have always been intertwined, and to Aristotle, the arts facilitate imaginative perception, engaging and refining capacities necessary for sound moral judgment. Aesthetics point toward the limit of knowledge and make the unknowable visible, so the devaluation of the arts leads to a deprivation of self-understanding. The perspective-widening world view formed by art increases the range of moral possibilities, as the moral agent cannot outline what cannot be imagined.