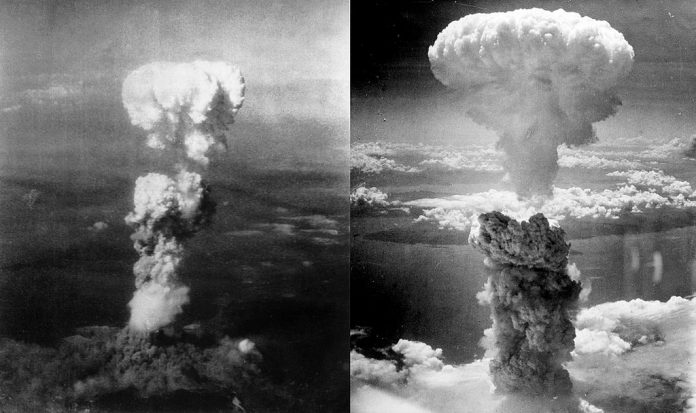

George Weigel, papal biographer, in a recent article in First Things, offers a defense of President Truman’s terrible decision in 1945 to destroy the two cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, along with most of their inhabitants, as a swift way to end the war with Japan.

As Mr. Weigel reminds us, it was seventy-five years ago this year, on August 6 and 9, 1945, that the United States for the first and only time in war used the newly-invented ‘bomb’, one based on Einstein’s and other’s new theories of physics, which unleashed unheard-of power latent in the nucleus of the atom. The ensuing blast – beyond anything previously imaginable – obliterated many square miles, killing instantly tens of thousands inhabitants, including women, children, babies – even a number of those in utero, we may presume – elderly, the sick, those in hospital and at home, young students at school – all of them, either incinerated in the nuclear inferno, or left so poisoned and burnt by radiation, or crushed by debris, that they died lingering deaths over days, weeks, months.

I wonder, should we commemorate such a tragic event by yet-another justification for what many – myself included – consider a reprehensible act? We might recall that Mr. Weigel nearly two decades ago – against the stern warnings of his own hero, Pope John Paul II – also rationalized the American invasion of Iraq in 2003, a decision that has since cost hundreds of thousands of lives, untold numbers of life-altering injuries, broken homes and families, the fleeing of almost every Christian person and vestige from the country, billions of dollars of debt, the unleashing of radical Islamic elements, and instability across the Middle East. And that’s before we get to the unending debacle of Afghanistan, where the war never ends.

But I digress, and we may yet disagree on those conclusions. I am no pacifist, and believe quite firmly in just war doctrine – but there are limits to what we may do, even in the most extreme situations, constrained, if you will, by the natural and divine law.

I wrote about Hiroshima a few years ago in Crisis, and Truman’s decision to drop the bomb, arguing for its intrinsic evil, responding to a previous article by a certain Mr. Jim Russel justifying the bombing.. They only published mine with the proviso that another article – I know – by an Air Force officer, also in support of Truman’s decision, stand alongside my own, I guess as some sort of moral ballast for the weakness of their case. They doth protest too much, methinks.

The decision to drop the bomb on two civilian targets was not an easy one. They did discuss detonating a nuclear device off the coast of Tokyo, to signify to the Japanese authorities its destructive power. And we know not what might have happened regardless, had America called their bluff. There is evidence the Japanese were near-collapse, and they had already made overtures to end the conflict; if a way had been found to allow them to surrender honorably, they might have gone for it (unconditional surrender has its own moral difficulties in any war). There is convincing evidence the Japanese were ready to give in – even on U.S. terms, not least with the entrance of Russia into the war, which made their situation untenable. Here is the testimony of Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz. Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet.

The Japanese had, in fact, already sued for peace. The atomic bomb played no decisive part, from the purely military point of view, in the defeat of Japan.

And the still stronger words of William D. Leahy, Chief of Staff to President Truman himself:

The use of (the atomic bombs) at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons. The lethal possibilities of atomic warfare in the future are frightening. My own feeling was that in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make war in that fashion, and wars cannot be won by destroying women and children.

There are, admittedly, any number of ‘what might have beens’, which may prove a distraction here from ‘what certainly was’. The moral quality of those most certain bombings must be discerned, so that we might avoid future evils. By the by, if you are not convinced by my meagre words, try the sharper and more analytical mind of the great philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe, who wrote against Harry Truman’s choice, when the latter was awarded an honorary degree from Oxford in 1958. Her essay follows in the footsteps of a previous one by Father John C. Ford in 1944, cogently condemning the previous firebombing of civilian targets by both sides in the brutal war. Father Ford, by the way, was one of the few on Pope Paul VI’s 1967 Birth Control Commission to stand firmly against contraception, along with the lay theologian Germain Grisez. His moral clarity allowed him to see to the core of both issues.

But back to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and Jim Russell’s 2017 article, which reads much like Mr. Weigel’s just published the other day. Oddly to my mind, both men state as part of their argument that their own fathers were servicemen in the Pacific theatre at the time. Why bring in Dad? One might think they are trying to justify the destruction of both cities by the hypothetical sparing of their fathers’ lives, who may have perished in the predicted bloody and brutal amphibious assault. But what of the ‘Dads’ – and Mums – going about their business on those fateful August mornings, incinerated, or what might even be worse, left to die in burning agony, with many watching their children do so around them? Not all the Japanese were in support of the war, and many welcome the Americans with open arms after their defeat.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m happy the Russell and Weigel fathers survived the war, and that both men have come into existence, and their family trees continue to flourish. But both their arguments are nearly undiluted proportionalism, and of a rather tendentious, emotional sort, that a lot of good justifies even great evil, so long as the good proportionately outweighs the evil. Double effect and all that.

That works, but only for physical evils, not for intrinsic moral evil. In fact, it is the Church’s firm and unchanging teaching that no amount of physical evil can outweigh even one deliberate act of moral evil. To quote Saint John Henry Cardinal Newman from chapter 5 of his Apologia:

The Catholic Church holds it better for the sun and moon to drop from heaven, for the earth to fail, and for all the many millions on it to die of starvation in extremest agony, as far as temporal affliction goes, than that one soul, I will not say, should be lost, but should commit one single venial sin, should tell one wilful untruth, or should steal one poor farthing without excuse.

This is not easy to read, never mind live out; but it’s true. And if this holds for ‘one single venial sin’, what are we to say about the destruction of untold numbers of innocent lives, even to save untold numbers of other innocent lives?

And we may also turn to the Pastoral Constitution on the Church (which Karol Wojtyla had a hand in writing), to a section also quoted in the Catechism, to which Mr. Weigel, like every Catholic, owes religious submission of mind and will:

Any act of war aimed indiscriminately at the destruction of entire cities of extensive areas along with their population is a crime against God and man himself. It merits unequivocal and unhesitating condemnation.

Mr. Weigel’s wayward principle here – that the bombing saved further slaughter, and hence was a prudent act – would in turn justify any number of other evils, not least should another such war dawn upon us. And to say that we were prepared for this evil by the preceding firebombing of Tokyo and Dresden is simply to justify a current evil by a previous one already committed. See Father Ford, above. Doubling down on evil is never a good idea.

This is a continuation of the principle of ‘total war’ – that anything goes in war, with women, children and civilians considered fair game and even ‘enemy combatants’ – which was rife amongst pagan societies in ancient and modern times, but condemned by the Church. Mediaeval warfare depended upon two sides bringing their best men to the field, duking it out – rather bloodily, one might admit – until one side surrendered. The wars of religion, especially the vicious one that goes by the name Thirty Years, reignited total war in Christianity, especially amongst quasi-pagan Prussian Protestantism, which continued into both World Wars. In reading for this article, I was unpleasantly surprised by certain conservatives’ philosophical justifications for American’s actions in the war, advocating for the wholesale slaughter of entire populations as an act of mercy – from Sherman in the Civil War all the way to Asia and beyond – so that conflicts might be ended ‘swiftly and mercifully’. Swift, perhaps, but what is merciful about the destruction of the innocent? And what of the souls of the perpetrators and their accomplices? How will they stand before God?

We should also recall that American hegemony in Japan after the war under General MacArthur facilitated the legalization of abortion, by the ‘Eugenic Protection Law’ of 1948, a quarter of a century before the horrific practice was made law in America. The widespread and continuing murder of their unborn, along with accompanying contraception, has now decimated the elderly nation, on an irreversible demographic death spiral – and we are now treading the same downward path. The concepts of ‘total war’ and abortion are not unconnected, but that is a tale for another time.

In the end, we must always, always do the right thing, and never the wrong thing, even if it costs us everything. After all, we are not made for this world, but for the next, and if we lose sight of eternal life – all things considered sub specie aeternitatis – then, really, all is lost. But if we die for truth, goodness and Christ’s own Way, then, regardless of the cost, all is gained.