APOSTOLIC PILGRIMAGE TO POLAND

HOLY MASS AT THE CONCENTRATION CAMP

HOMILY OF HIS HOLINESS JOHN PAUL II

Auschwitz-Bierkenau, 7 June 1979

1. “This is the victory that overcomes the world, our faith” (1 Jn 5:4).

These words from the Letter of Saint John come to my mind and enter my heart as I find myself in this place in which a special victory was won through faith; through the faith that gives rise to love of God and of one’s neighbour, the unique love, the supreme love that is ready to “lay down (one’s) life for (one’s) friends” (Jn 15:13; cf. 10:11). A victory, therefore, through love enlivened by faith to the extreme point of the final definitive witness.

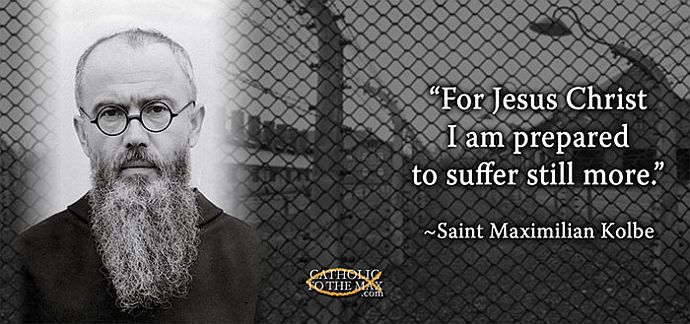

This victory through faith and love was won in this place by a man whose first name is Maximilian Mary. Surname: Kolbe. Profession (as registered in the books of the concentration camp): Catholic priest. Vocation: a son of Saint Francis. Birth: a son of simple, hardworking devout parents, who were weavers near Łódź. By God’s grace and the Church’s judgment: Blessed.

The victory through faith and love was won by him in this place, which was built for the negation of faith—faith in God and faith in man—and to trample radically not only on love but on all signs of human dignity, of humanity. A place built on hatred and on contempt for man in the name of a crazed ideology. A place built on cruelty. On the entrance gate which still exists, is placed the inscription “Arbeit macht frei”, which has a sardonic sound, since its meaning was radically contradicted by what took place within.

In this site of the terrible slaughter that brought death to four million people of different nations, Father Maximilian voluntarily offered himself for death in the starvation bunker for a brother, and so won a spiritual victory like that of Christ himself. This brother still lives today in the land of Poland and is here with us.

But was Father Maximilian Kolbe the only one? Certainly he won a victory that was immediately felt by his companions in captivity and is still felt today by the Church and the world. However, there is no doubt that many other similar victories were won. I am thinking, for example, of the death in the gas chamber of the concentration camp of the Carmelite Sister Benedicta of the Cross, whose name in the world was Edith Stein, who was an illustrious pupil of Husserl and became one of the glories of contemporary German philosophy, and who was a descendant of a Jewish family living in Wroclaw.

I do not want to stay only with those two names, when I ask myself, was it only he or she alone…? How many similar victories were here? These victories were made by people of different faiths, different ideologies, certainly not just believers.

We want to embrace with a feeling of deepest reverence each of these victories, every manifestation of humanity. They were the negation of a system of systematic negation of humanity.

In the place of terrible devastation of humanity and human dignity – there is victory of humanity!

Can it still be a surprise to anyone that the Pope born and brought up in this land, the Pope who came to the see of Saint Peter from the diocese in whose territory is situated the camp of Auschwitz, should have begun his first Encyclical with the words “Redemptor Hominis” and should have dedicated it as a whole to the cause of man, to the dignity of man„ to the threats to him, and finally to his inalienable rights that can so easily be trampled on and annihilated by his fellowmen? Is it enough to put man in a different uniform, arm him with the apparatus of violence? Is it enough to impose on him an ideology in which human rights are subjected to the demands of the system, completely subjected to them, so as in practice not to exist at all?

2. I am here today as a pilgrim. It is well known that I have been here many times. So many times! And many times I have gone down to Maximilian Kolbe’s death cell and kneeled in front of the execution wall and passed among the ruins of the cremation furnaces of Birkenau. It was impossible for me not to come here as Pope.

I have come then to this special shrine, the birthplace, I can say, of the patron of our difficult century, just as nine centuries ago Skałka was the place of the birth under the sword of Saint Stanislaus, Patron of the Poles.

I come not only to honour the patron of our century, I come with the aim together with you, independent of what your faith is, once again to take care of the human being.

I have come to pray with all of you who have come here today and with the whole of Poland and the whole of Europe. Christ wishes that I who have become the Successor of Peter should give witness before the world to what constitutes the greatness and the misery of contemporary man, to what is his defeat and his victory.

I have come and I kneel on this Golgotha of the modern world, on these tombs, largely nameless like the great tomb of the Unknown Soldier. I kneel before all the inscriptions that come one after another bearing the memory of the victims of Birkenau in languages: Polish, English, Bulgarian, Romany, Czech, Danish, French, Greek, Hebrew, Yiddish, Spanish, Flemish, Serbo-Croat, German, Norwegian, Russian, Romanian, Hungarian, and Italian.

In particular I pause with you, dear participants in this encounter, before the inscription in Hebrew. This inscription awakens the memory of the People whose sons and daughters were intended for total extermination. This People draws its origin from Abraham, our father in faith (cf. Rom 4:12), as was expressed by Paul of Tarsus. The very people that received from God the commandment “Thou shalt not kill”, itself experienced in a special measure what is meant by killing. It is not permissible for anyone to pass by this inscription with indifference.

(To continue reading, please see here)