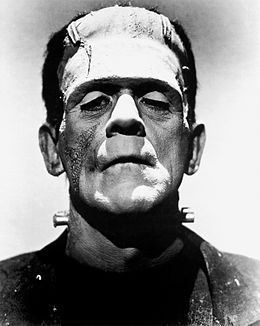

No mortal could support the horror of that countenance. A mummy again endued with animation could not be so hideous as that wretch. I had gazed on him while unfinished. He was ugly then, but when those muscles and joints were rendered capable of motion it became a thing such as even Dante could not have conceived. – Victor Frankenstein

This past week, I listened to Dan Stevens’ narration of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. I love audio books, and this is an excellent narration! The story, however, was not what I had expected. I have not watched any of the numerous film versions, so my surprise at the novel was not due to false expectations inculcated by Hollywood.

The first shock came with the description of Frankenstein’s immediate revulsion toward his creature. From the moment the creature opened its “watery eyes” it became the object of Frankenstein’s loathing and hatred. Call me naïve, but I was expecting him to be ecstatic at having accomplished his goal, for him to love his creation, until it – he – became unlovable due to its own misdeeds. Frankenstein, however, hates the creature from its very inception, not because of any misdeeds on the part of the creature, but because of its hideous appearance and enormous proportions, which were bestowed by Frankenstein himself!

Hating one’s own work because it is hideous seems hypocritical. Why hate the art, when it is the artist who is at fault? When I draw or paint something and it turns out poorly, there is a temptation to hate the work because it isn’t what I had hoped for and its deficiencies remind me of my own shortcomings as an artist. That’s not a particularly difficult reality for me to face and forgive because being an artist isn’t what’s most important to me; however, for those who define themselves by their art, producing something hideous is a tragedy. If I am what I create, and what I create is hideous, then I am hideous! That’s the implicit logic, it seems, of Frankenstein’s overwhelming hatred of his creature.

Frankenstein’s ensuing rejection and abandonment of his creation were the second surprise. When the creature opens its eyes, Frankenstein runs away. The creature, knowing nothing because it is a newborn, wanders out of the apartment and out of town. Once again, call me naïve, but I assumed Frankenstein would try to remedy the situation. Instead, he is at first relieved by the disappearance of his creation and then he spends months recovering from a nervous illness. When he recovers, he tries to go back to life as it was before, but those plans are destroyed by the murder of one of his brothers. Some evidence leads Frankenstein to suspect that his creature is the killer, but he says nothing. Even when an innocent girl is accused, tried, and executed for the crime, he says nothing. He makes excuses for his silence and refuses to take responsibility for his creation.

When Frankenstein does eventually meet his creature (the creature has been awaiting a suitable time to confront his creator and make a proposal), he is understandably irate. Frankenstein argues that the creature should die because it should not have been created, because it is a “monster”, “fiend”, “devil”, and “demon”. The creature, however, responds that he himself is the victim of Frankenstein’s folly. Frankenstein set him on the path to misery and fiendishness by abandoning him, a monster, to a cruel life of solitude. The creature convinces his creator to fashion a mate fit for him. He promises that if Frankenstein makes him a bride, they will disappear and live out their days in peace and seclusion, but if Frankenstein refuses, then the creature will execute a horrible revenge.

Frankenstein accepts the deal and begins the long labour of forming a female version of his creature. However, as he approaches the completion of his work he begins to contemplate what horror he might be unleashing upon the world. He thinks to himself:

Even if they were to leave Europe and inhabit the deserts of the new world, yet one of the first results of those sympathies for which the demon thirsted would be children, and a race of devils would be propagated upon the earth, who might make the very existence of the species of man a condition precarious and full of terror (Bk 3, Ch 3).

At the height of Frankenstein’s doubt, the “demon” appeared in the window:

As I looked on him, his countenance expressed the utmost extent of malice and treachery. I thought with a sensation of madness on my promise of creating another like to him, and trembling with passion tore to pieces the thing on which I was engaged. The wretch saw me destroy the creature on whose future existence he depended for happiness and, with a howl of devilish despair and revenge, withdrew (Bk 3, Ch 3).

As promised, the creature carries out his terrible revenge by first killing Frankenstein’s best friend and then his wife.

The story ends with Frankenstein chasing his creature across Asia and deep into the arctic in a futile effort to have his revenge and rid the world of the “monster’s” existence. However, Frankenstein dies of exhaustion before catching his enemy, and in the final scene of the book the creature stands over the corpse of his dead creator and laments his pitiful existence to the ship’s captain. In this final scene, the creature admits that he is a wretch, but he places the blame for his wretchedness in the hands of his creator and all of humanity:

When I run over the frightful catalog of my sins, I cannot believe that I am the same creature whose thoughts were once filled with such sublime and transcendent visions of the beauty and the majesty of goodness, but it is even so. The fallen angel becomes a malignant devil, yet even that enemy of God and man had friends and associates in his desolation. I am alone.

The monster sought friends and companionship, but he was repeatedly rejected and scorned by humanity, and is perforce asks,

Am I to be considered the only criminal? (Bk 3 Ch 8)

The answer to that question is, of course, no; he is not the only criminal. He was wronged by many people. He was abandoned by his creator. He was also stoned, beaten, shot, and hunted by others. The fact that he was wronged, however, does not justify his own evil deeds. He is treated like a monster and a demon and so, despite his initial desire to be good, he assumes the persona of the monster. He chooses to perpetuate the evil that he experienced and so he brings death, destruction, and misery to many more people. Objectively, he is not the only criminal in the story, but he is the worst criminal. None of the other crimes in the story compare with killing four innocent people. Subjectively, however, Frankenstein and his creature are opposite sides of the same coin, and the creator shares in the crimes of his creature.

One of the recurring themes in the book is the “otherness” of the creature. He is rejected by everyone because of his appearance. Frankenstein considers him to be another species, and fears that if he were given a mate, they would produce “a race of devils” that could destroy humanity. Even the creature, despite his desire to be with humanity, sees himself as something different. He likens himself to both Satan and Adam because he is unique and the first of his kind. He says to Frankenstein, “I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel whom thou drivest from joy for no misdeed” (Bk 2 Ch 2). Therefore, he argues that Frankenstein owes him a mate fit for himself. Is this true? Is he really alone and entirely “other”? No, he is not a new Adam, but rather another sinful child of Adam. If we use Aristotle’s definition of man, “a rational animal”, then Frankenstein’s creature is a man. He is a “monstrous” man, exaggerated in his proportions and unique in his birth, but he is a man nonetheless. Their relationship is that of father and son, not creator and creature.

This “otherness” of the creature is used by both Frankenstein and the creature to justify their sinful behaviour. The “otherness” of the creature is Frankenstein’s “red herring”. If we accept that the creature is entirely “other”, then we are likely to take a side. Some will take the side of Frankenstein and say that the creature should be destroyed: ‘Yes, Frankenstein sinned in having created a “monster”, but he is righteous in his desire to make amends for his sin by killing the monster.’ Others may take the side of the creature and say that he is a victim of the folly of his creator: ‘Yes, the creature killed innocent people, but it was only because he was abandoned to solitude and persecution by his creator.’ The truth is that they are both guilty and each is responsible for his own actions and omissions. Frankenstein is a terrible father. He completely fails in his responsibilities as a father and sins gravely against his son. But, the creature is a terrible son. He magnifies the sins of his father and perpetuates those sins in monstrous ways. The “otherness” of the creature is merely an excuse that each uses to justify his own inability to take responsibility for his own actions.

Perhaps I was surprised by the story because I am naïve. I had assumed that Frankenstein would love his creature until it became monstrous in its actions, but instead he hated it because it was monstrous in its creation. “Transgression speaks to the wicked deep in his heart; there is no fear of God before his eyes. For he flatters himself in his own eyes that his iniquity cannot be found out and hated” (Ps 36:1-2). How can a father not love his son? How does one so easily shift blame and responsibility from one’s own shoulders to those of others? I expected more from Frankenstein, but perhaps I do not fully realize my own capacity to be Frankenstein? And could not the same be said for us all?