Festival and Ferial

Anna Rist

Kaufmann Publishing, St. Simon’s Island [GA], 2014

ISBN : 978-0-9905329-3-4

In one of his Odes (IV.2) Horace describes the danger of trying to emulate the majestic Greek poet Pindar. Such daring, Horace says, would bring the would-be poet to a disastrous end, another Icarus flying too high on his waxed wings, only to crash and, perhaps, give his name to a glassy sea.[1] Horace proceeds to described Pindar’s grandeur, his themes and his techniques in what (critics say) is a Latin version of Pindar himself. Mrs. Rist, as a classicist, would have been familiar with the famous Ode, and like Horace she dares to imitate the master. Two characteristics are singled out in Horace’s account of Pindar’s methods:

. . . per audacis nova dithyrambos

verba devoluit numerisque fertur

lege solutis

. . . he rolls down new words in his daring dithyrambs

and is carried along in free

unregulated rhythms.[2]

Acting upon this precedent, Mrs. Rist does not hesitate to invent neologisms or, more commonly, to place familiar words in unusual settings so as to reveal hidden aspects of the range of their meanings.[3] A striking instance is the momentary shock and subsequent readjustment occasioned by the word “buddy, followed by “barkburst” in Cherry Trees in Holy Week:

my here from study

keyboarded sight

lifts to one buddy

birthling . . .

eyefuls of barkburst . . .

which become a symbol of the risen Christ:

with Life new uncurst

in flower of our kind!

There are similarly striking phrases in virtually every poem. One also sees in the above excerpt the second Pindarian technique of “unregulated rhythms,” in which traditional meter is largely abandoned in the interest of conceptual capsules. There are, nevertheless, two sonnets, in form and in tone Shakespearean, that provide the reader with a good instance of her subtlety as well as her skill. One celebrates a Tuscan saint no one will have heard of: Saint Agnes of Montepulciano. Woven into the sonnet are her feast day (April 20), which was also “Easter Eve” in the year of the poem’s creation, Shakespeare’s approaching day of birth and death (April 23), and—of all things—a sly reference to Hitler’s birthday (April 20, 1889) along with a notice of Mrs. Rist’s Jewish descent: “our end”

April ambivalent! This day has fated

with Heils our end, but watches for Shakespeare

to set as rise, like every orb created. . . .[4]

The other sonnet is a wicked description of the harm that the web has done to language. It ends with a rhyming couplet that vies with Shakespeare’s own:

cocoon the globe, trammel each busy weaver

confounding the deceived and the deceiver.

The first prerequisite to a successful poem is sensitivity to human experience, which then, having been refined in the crucible of imagination, can be transmitted to the reader. Horace again: . . si vis me flere, dolendum est/primum ipsi tibi (“. . . if you want me to weep, you must first have grieved yourself”).[5] Mrs. Rist is admirably suited to her task. She is a classical scholar, a wife and mother—and now a grandmother—and a trenchant commentator on Christianity and contemporary culture. But more than experience has been incorporated into the opus. A lifetime of reading and study has given her an acquaintance with the broad sweep of western civilization as well as a sensitivity to language and the power of words.

The title, Festival and Ferial, describes the main sections of the book. The first follows the Church year, beginning with Advent and proceeding through the great feasts, ending with All Souls. In the second, Ferial, Mrs. Rist presents a series of poems that are quasi-autobiographical reflections on the wide-ranging experiences of a life that moved from England to Canada and back to England, combined with a long-term relationship with the Tuscan town of Semproniano.[6] In one—Goliardic (1950s)[7]—she wryly condenses her life into a couple of pages: “When that I was naïve nineteen,/I craved a life of diversity. . . .” Mrs. Rist’s allegiance to Catholicism, evident throughout, is highlighted by an unusual feature in a book of poetry. A third section, The Shakespeares of Henley Street, is a one-act play that accounts for Shakespeare’s abrupt departure from Stratford in 1586. She is kind to him, underlining his double commitment to Catholicism and to his wife and children. It is an engrossing picture of domestic life in Elizabethan times, learned without being pedantic and sympathetic for followers of “the old faith.” She adroitly evades one major pitfall of anyone composing sixteenth-century dialogue: it rings true without at all sounding like a Hollywood film of the forties.

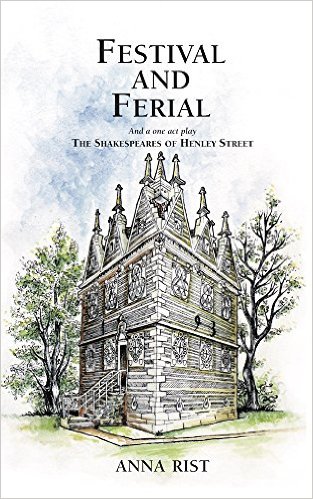

It remains now only to comment on a few of the poems in a manner that will send the reader to the entire collection. But first, there’s the cover, on which is depicted a small, vaguely gothic structure, triangular in shape. It is Rushton Triangular Lodge, built by Sir Thomas Tresham in 1597 as a witness to his faith in the Trinity. Mrs. Rist uses his stubborn loyalty to Catholicism, as well as his son Francis’s participation in the Gunpowder Plot, as an entry into her poem for Trinity Sunday, One in Three:

old Thomas Tresham

. . . fixing

in intricate symbol

the Ground of all Being

revealed as triune

as Father’s Son’s Spirit’s

distinguished Unity’s

intergral interchange

of the tripersonal

fluctuant Godhead.

One of the most ambitious and successful is Flying from Stanboul: 29th June, Sts Peter and Paul. The immensely rich history of the region—Jewish, Grecian, Roman, Christian, Moslem—is evoked as the physical journey is transformed into a movement from east to west, and from East to West—“Set rigid wing on course from Rome/the New to the Undying”—and from the old to the new:

soon to see is Tiber snaking

about the City, skirting with his meanders

the twin sepultures of her Second Founders

not from the wolf but from the Shepherd fed.

Not surprisingly, the saints appear. Our Lady, of course, in the cycle of her feasts: Immaculate Conception (“Driven snow/is no/comparison/being too cold”), Candlemas (“earth and heaven/partake your Purification”), Annunciation (in the form of a dialogue between Kyria Miriam Theotokos and Loukas) and so on. Easter Dawning is a galloping account of the race to the tomb, narrated by Peter—“Run, young John, . . . pound along,” till at the end John stands aside: “Our Master’s Rock/and designated witness./Go you the first inside!” A long poem, For John, celebrates Saint Monica although the matter of the verse is, like the woman herself, mainly concerned with her son Augustine. The “John” of the title is Mr. Rist who is honoured here for his splendid book Augustine: Ancient Thought Baptized.[8] There is another Song for John which is a sort of elegy in advance. She reflects on their long life and “together prepare we well our wings/for flight past the zone of time!”

Her wit is trenchant, devastating, and there is plenty of material for its exercise. Sex-wrecks, for instance, describes authentic married love:

Augustine for our nature

sovereign medicament

had mingled in one tincture

faith, offspring, sacrament.

contrasting it with today’s “love tricked out in feigned clothes.” Freud, too, gets his comeuppance.

In short, we have here a wonderful, wise and entertaining collection of poems, all the more remarkable for having been written in a secular, sensualist age.

Daniel Callam, C.S.B.

[1] Not so the modern traveller, who airborne escapes the fate of Icarus: “Lift steel underbelly;/though sunstruck Icarus fell the/once, earth’s magnet under/yields you rebound in thunder” (p. 32).

[2] Horace: Odes and Epodes, edited and translated by Nial Rudd, Loeb Classical Library, no. 33 (Cambridge [MA]: Harvard University Press, 2004), p. 222.

[3] Shakespeare, of course, was the master of this technique, as in the “sullen earth” of Sonnet 29: “Yet in these thoughts, myself almost despising/ Haply I think on thee, and then my state,/Like to the lark at break of day arising/From sullen earth, sings hymns at heaven’s gate.”

[4] April 20 is also Mrs.Rist’s birthday. “Agnes of Montepulciano, whose feast moreover, was on my birthday—redeeming it from the stigma of a dies nefasta it had acquired from being the birthday of Hitler and a Nazi holiday.” Anna Rist, We Etruscans: Old and New in a Forgotten Landscape (Lutterworth Press: Cambridge, 2005), p. 170.

[5] Horace, Ars Poetica, ll. 102-03, Horace: Satires, Epistles, Ars Poetica, revised edition, edited and translated by Jeffrey Henderson, Loeb Classical Library, no. 194 (Cambridge [MA]: Harvard University Press, 1929), p. 458.

[6] Anna Rist, We Etruscans: Old and New in a Forgotten Landscape (Lutterworth Press: Cambridge, 2005). The book contains a bonus for admirers of Mrs. Rist’s verse, in three poems not included in Festival and Ferial: Autostrada 1990, an amusing account of the discomfort of motor travel across Europe in summer; Redeunt SATURNIA Regna, which describes a visit to a spa in the town of Saturnia; and, as envoy, HOMING SOUTH: for Charles, “Charles” being Father Charles Leland, C.S.B., a long-time family friend who for many years taught English at Saint Michael’s College in the University of Toronto.

[7] A Goliard is defined by the OED as “one of the class of educated jesters , . . . authors of loose or satiric Latin verse in the 12th and 13th centuries.”

[8] John Rist, Augustine: Ancient Thought Baptized (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1996).