Two creeds are in common use among us: the Apostles’ Creed and the Nicene Creed, which we use on liturgical occasions, and is a propos especially on Trinity Sunday. A moment’s thought makes it clear that both are expanded versions of Our Lord’s command, “Going therefore, make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.”[1] With the passage of time, the candidate for baptism would have been invited to identify the Father as the creator of heaven and earth, the Son as the redeemer who died and rose again, and the Spirit who continues the work of the Son in the one, holy, Catholic and apostolic Church. The Apostles’ Creed may not have been actually composed by the Apostles, despite a charming legend to that effect, but it is rightly called apostolic in that it summarizes their teaching. Its current form assumed shape gradually in the Roman Church, attaining finally the wording we use today around the year A.D. 700. It is a convenient brief summary of the teachings of the Church.

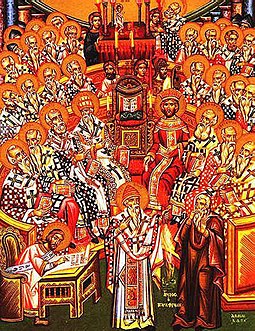

So is the Nicene Creed, but its history is more complicated. One might even say, “more thrilling,” for it exhibits another function of creeds in the early Church, viz., to counter false teaching, to confound heretics who wanted to alter our fundamental beliefs. It’s called the Nicene Creed because it has been associated with the first General Council, which took place in A.D. 325 in the town of Nicaea (modern Turkey). It must have been a remarkable sight to find the bishops assembled there, in the palace of the Emperor Constantine, only a few years after the last and fiercest persecution of Christians by the Roman Empire. Some of the clergymen gathered there, we are told, bore on their bodies the marks of torture which they had undergone not much more than a decade earlier. As I say, they were gathered there to refute a false teaching, that of an Egyptian priest named Arius. His doctrine was immensely appealing because it fit in perfectly with the thinking of the time. It was simple; he claimed that Jesus was not literally divine, that is to say, he was not equal to the Father, although he was the highest creature; as the word of God, he had been the agent of creation and as incarnate he had been man’s redeemer. It was hard to argue with Arius because he was a master in the use of Scripture. As often happens in religious debates, the Bible was the battleground rather than the arbiter of the disagreement. Arius had a text ready to refute anything that his opponents said. If they quoted John’s Gospel, where Jesus said, “The Father and I are one,” Arius would counter, “but Jesus also said, ‘the Father is greater than I,’” and so on. That’s not surprising, for the New Testament had not been written to correct an error that arose some three hundred years later.

What was to be done? The matter was rendered all the more perplexing in that Arius was willing to use language that, taken literally, would have admitted the full divinity of Christ. But he said that such expressions were merely metaphors. After all, hadn’t Saint Peter himself done the same thing when he wrote that Christians by their baptism had become “partakers of the divine nature”?[2] The same statement could be applied to Jesus, Arius said, albeit in a more sublime manner. The bishops chose a desperate stratagem. They went outside the language of Scripture, but they did so only to preserve the biblical teaching. They inserted a word into their traditional creed that neither Arius or his followers could admit, at word that is still in the creed today. The word is “consubstantial,” (homo-ousios in Greek) and it expresses the truth that Son is one in being, is at the same level of existence as the Father; he is fully and literally divine. That word has been called the most famous word of the fourth century, and, as any Church historian can tell you, it is no exaggeration so to describe it. When, therefore, you join in reciting the Nicene Creed you should regard it as a battle cry, like soldiers holding the citadel intact against the onslaught of the enemy. And the phrasing of the central section lends itself to this exuberance; it really should be shouted: “I believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ, . . . God from God, light from light, true God from true God, begotten, not made. . . “Ah! that’s a good line: “begotten “is used of the Son to indicate that he is of the same nature as the Father. He’s not “made,” and therefore he is not a creature. Then comes the clincher: “consubstantial with the Father.” “And that,” the great Athanasius said, should silence the Arians once and for all.”

There’s a lesson in all this history for us Catholics today. In the fourth century the Church was confronted with a pagan society: ancient Greece. There was much to admire in Greek culture, and also much to deprecate. The challenge then was to honour what was worthwhile and reject what was incompatible with the Gospel. It’s no wonder that mistakes were made on either side: some were too timid, others too rash in their attitudes. And today we are similarly engaged as the Church confronts modern society with its many good aspects and many . . . not so good. The sorting out of one from the other is not easy, as people today ascribe, almost unconsciously, to current modes of thought and behaviour. Some Catholics may prefer to hide away, refusing the challenge, but that would be to stagnate and so wither on the branch. Our allegiance to the creeds is the best safeguard against a denial of our past or a fear of the future. Its fundamental message is that everyone is called to embrace fully the new supernatural life that Jesus, sent by the Father, has won for us by his great acts and that is made available today through the presence of his Spirit who enters our minds and hearts at baptism and confirmation.

[1] Matt 28:19

[2] 2 Pet 1:4.