Good Christians, now rejoice! The timeless tale of Ebenezer Scrooge and his encounters with three ghosts is steeped in Christian references, symbolism, and themes often overlooked by casual readers and modern adaptations. Published in December of 1843, A Christmas Carol is one of the most well-known yuletide stories of modern times. Nearly 200 years after Dickens put pen to paper, his story remains often read and frequently adapted for stage and screen. Classic true-to-the-book scripts have been crafted from the author’s original manuscript and great liberties have been taken in parodies and modern applications of the classic story. The first film adaptation was a silent one released 1910, only 40 years after Dickens’ death.

Written in five parts called staves, A Christmas Carol takes readers on a short but transformative journey in a day or two—or three, maybe—of the life of crotchety miser Ebenezer Scrooge. Perhaps stemming from Dickens’ own Christian beliefs, A Christmas Carol is tale of conversion, love, and hope. This ghost story of Christmas carries a Christian message supported by direct references and not-so-subtle nods to the faith. Many of these aspects of the nineteenth-century novella, though, have eroded in modern adaptations. This article intends to shift the focus of one of Dickens’ most famous works back to its Christian roots through examining the original 1843 manuscript.

Stave I: Dickens’ Christianity

Born of Anglican parents who practiced their faith fleetingly, Charles Dickens attended Baptist services as a child and spent time in Unitarian chapels later in his life. He is said to have had a particular dislike of Evangelicalism and Catholicism (Schlicke, Timko). This was not an uncommon sentiment in England in the early part of the nineteenth century as tensions created by Henry VIII’s 1534 split with the Catholic Church lingered. Plus, Dickens disliked doctrine and dogmatic teachings. Neither devoted to the Catholic Church nor any specific Protestant sect—even the Church of England of which he was formally a member—Dickens did consider himself a Christian (Timko).

He was, in fact, so infatuated the idea of Christianity and the stories and parables of the Holy Bible, that he was inspired to write a book especially for his children. In 1849, Dickens completed his three-year project: The Life of Our Lord, a short hand-written piece based upon the Holy Gospels. Its intent was to share his thoughts and guide his children in the way of Christian faith. The book was published posthumously in 1934 will full consent of the Dickens family.

An evangelist of sorts, Dickens used The Life of Our Lord and his fictional works to convey Christian messages. A Christmas Carol is a timely and timeless example.

Stave II: The Religious Climate of Nineteenth-Century England

Christianity was the prominent religion in England in the 1800s and remains so in the present-day United Kingdom. Published as a contemporary tale in 1843, A Christmas Carol takes place in London. “Scrooge had as little of what is called fancy about him as any man in the city of London” (21-23). This by default places the story in a Christian community. References of this religious climate abound in Dickens’ narrative. “He was endeavouring to pierce the darkness with his ferret eyes,” the author wrote of Scrooge, “when the chimes of a neighbouring church struck the four quarters. So he listened for the hour” (44). In predominantly Christian communities it is not uncommon for the local church to be the official declarer of each quarter hour.

Later in the narrative, Dickens makes something of an assumptive statement regarding the interconnection of church and community. Walking with the Ghost of Christmas Past, Scrooge recognizes “every gate, and post, and tree; until a little market-town appeared in the distance, with its bridge, its church, and winding river” (52). The matter of a church being part of a town was so commonplace in Christian England that the author’s inclusion of it may have been reflexive. It was simply the way of things.

In stave three of A Christmas Carol, Dickens makes it a point to include churchgoing at the center of his description of Christmas activities. Food shopping and dinner celebrations chronologically flank church attendance on Dickensian Christmas Day. Scrooge accompanies the Ghost of Christmas Present on a walk through the streets of London as “the steeples called good people all, to church and chapel, and away they came, flocking through the streets in their best clothes, and with their gayest faces” (92).

In the final stave of Dickens’ novella, Scrooge hears Christmas Day courtesy of multiple London churches. “He was checked in his transports by the churches ringing out the lustiest peals he had ever heard,” Dickens describes. “Clash, clang, hammer; ding, dong, bell. Bell, dong, ding; hammer, clang, clash! Oh, glorious, glorious!” (160). Christmas Day had a sound in 1843 London, and this was it.

Stave III: Direct References to the Christian Faith

The simple fact that the events of A Christmas Carol take place in London in 1843 make Christianity easy to incorporate into the narrative. Had Dickens not wished to specifically point out Christian values or even to evangelize a bit, though, he could have stopped with such opportune inclusions. Yet, he did not. Throughout the 170 pages of his manuscript, Dickens repeatedly makes direct references to Christianity and its ideologies.

It begins in the beginning.

Before the appearance of Jacob Marley, before the three spirits come to call, and before his climactic conversion, Scrooge gets a visit from an earthly vessel of Christianity: his nephew. In one great speech, Fred the nephew establishes the Christian tone for Scrooge’s struggles and eventual conversion. “I have always thought of Christmas time, when it has come round—apart from the veneration due to its sacred name and origin, if anything belonging to it can be apart from that—as a good time,” Scrooge’s nephew explains while positioning Christmastime and its sacred roots as inseparable. “A kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time; the only time I know of, in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of people below them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys. And I say, God bless it!” (13).

Fellow passengers to the grave.

The phrase echoes Christian teaching of equality among equals. Paul the Apostle wrote to the Church at Philippi, “Do nothing out of selfishness or out of vainglory; rather, humbly regard others as more important than yourselves, each looking out not for his own interests, but also everyone for those of others” (Philippians 2:3-4 NAB). Fred’s indirect reference to this apostolic teaching points to Scrooge’s shortcomings and foreshadows his conversion. The tone appropriately set, Dickens offers more Christian references through a singing boy, Jacob Marley, Belle, and the Cratchit family.

While songs and music are referenced in general ways some eleven times in the pages of A Christmas Carol, only one musical piece is specified—by its lyrics. “The owner of one scant young nose … stooped down at Scrooge’s keyhole to regale him with a Christmas carol … ‘God bless you, merry gentleman! May nothing you dismay!’” (19). Scrooge chases away the boy—to whom he later wishes he had shown charity—before the subsequent lyrics. “Remember Christ our savior was born on Christmas Day.” Alas, gone astray, Scrooge had not yet known comfort or joy. This is evident in another direct reference to Christian ideology when he refuses to financially support efforts to feed and clothe the poor. “Under the impression that they scarcely furnish Christian cheer of mind or body to the multitude … a few of us are endeavouring to raise a fund to buy the Poor some meat and drink, and means of warmth. We choose this time, because it is a time, of all others, when Want is keenly felt, and Abundance rejoices” (17).

When Scrooge directs the charitable gentlemen to put him down for nothing, one of them assumes Scrooge wishes his donation to be quiet and uncredited. The question “You wish to be anonymous?” places the Gospel of Matthew in the heart of the inquiring portly gentlemen. “When you give alms, do not let your left hand know what your right is doing, so that your almsgiving may be secret. And your Father who sees in secret will repay you” (Matthew 6:3-4). Scrooge was not heeding the Gospel’s advice, but he would leverage a later opportunity. First, he had to entertain some guests, beginning with his deceased business partner Jacob Marley.

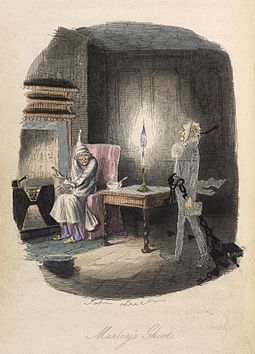

Marley, upon making himself comfortable in his former quarters now occupied by Scrooge, laments his squandered Earthly life. His dialog is the first direct Christian reference in Dickens’ novella. “Not to know that any Christian spirit working kindly in its little sphere, whatever it may be,” the ghostly Marley proclaims, “will find its mortal life too short for its vast means of usefulness” (37). This line is conspicuously absent from many stage and film adaptations of A Christmas Carol. Without significant digression into a topic worthy of its own many pages, there is value in noting a present-day fear of words such as “Christian” and even “Christmas.” Aversion to possible offense stifles vocabulary to a point of diminished meaning and broad but empty sentiment.

“I have none to give,” the Ghost of Marley tells Scrooge who begs for comfort. “It comes from other regions, Ebenezer Scrooge, and is conveyed by other ministers, to other kinds of men” (35). Ministers indeed; priests and prophets speak comfort to the selfless, the faithful, men unlike Scrooge. The man who lives for nothing higher than himself closes himself to God’s grace and its accompanying comfort. The man living a devotion to sin does not know joy. Scrooge knew sin. Beyond his lacking in love and charity, his most obvious sin was that of misplaced worship. It was pointed out to him early in life.

“Another idol has displaced me,” young Belle tells her beloved Scrooge.

“What Idol has displaced you?”

“A golden one” (70).

This short exchange between Belle and Scrooge directs the reader to God’s first commandment warning against worship of false idols. “I am the Lord your God … You shall not have other gods beside me. You shall not make for yourself an idol or a likeness of anything in the heavens above or on the earth below or in the waters beneath the earth; you shall not bow down before them or serve them” (Exodus 20:2-5).

Bob and Tim Cratchit were among the good people who went to church on that Christmas Day in 1843. “He had been Tim’s blood horse all the way from church, and had come home rampant” (96). This leads to a direct reference not only to church, but to Jesus Christ Himself. Bob Cratchit recalls to his wife, “[Tim] told me, coming home, that he hoped the people saw him in the church, because he was a cripple, and it might be pleasant to them to remember upon Christmas Day, who made lame beggars walk, and blind men see” (98). Tim’s “childish essence was from God” (151).

“Jesus said to them in reply, ‘Go and tell John what you hear and see: the blind regain their sight, the lame walk, lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have the good news proclaimed to them. And blessed is the one who takes no offense at me’” (Matthew 11:5).

Tim is not the only young Cratchit in Dickensian London to be called by a Christian name. Three of Timothy’s five siblings are mentioned by name in an A Christmas Carol: Martha, Peter, and Belinda—the only one whose name is absent from the Bible. Timothy was the first bishop of the Church at Ephesus and is directly addressed in at least two letters from the Apostle Paul (1 Timothy, 2 Timothy). He also would likely have been familiar with Paul’s more general letter to the Ephesians. The Apostle and Timothy encounter each other in Timothy’s youth as told in Acts of the Apostles. “[Paul] reached Derbe and Lystra where there was a disciple named Timothy, the son of a Jewish woman who was a believer” (Acts 16:1). In his second letter to the Bishop of Ephesus, the Apostle reminded him of their meeting. “I recall your sincere faith that first lived in your grandmother Lois and in your mother Eunice and that I am confident lives also in you” (2 Timothy 1:5).

The biblical Martha is often criticized in homilies and commentaries for busying herself after welcoming Jesus into her home. Perhaps she was a worker who occupied herself with tasks as a habit or by necessity. Dickens’ Martha was—an apprentice at a young age to help support her family. “We’d a deal of work to finish up last night … and had to clear away this morning, mother!” (96). Here’s the interesting parallel: “Martha, Martha,” Jesus says in the Gospel of Luke. “you are anxious and worried about many things. There is need of only one thing” (Luke 10:41-42). “Well! Never mind so long as you are come,” Mrs. Cratchit says to Dickens’ Martha. “Sit ye down before the fire, my dear, and have a warm, Lord bless ye!” (96).

Peter Cratchit is the namesake of Saint Peter, the apostle who would become first Pontiff of the Catholic Church. The eldest Cratchit son, Peter stands to inherit the patriarchy and become head of the family. “Peter … had a book before him. The mother and her daughters were engaged in sewing. But surely they were very quiet! ‘And He took a child, and set him in the midst of them.’ Where had Scrooge heard those words? He had not dreamed them. The boy must have read them out, as he and the Spirit crossed the threshold. Why did he not go on?” (147).

Had Peter, or whomever read those words from Mark’s Gospel, gone on, Scrooge would have heard, “and putting his arms around it he said to them, ‘Whoever receives one child such as this in my name, receives me; and whoever receives me, receives not me but the One who sent me’” (Mark 9:36-37). Christ’s own words are woven into Dickens’ narrative, yet this scene, too, is often removed from films and stage productions. It is easy to omit direct references like this when adapting the novella into a script, though the probable motivation remains disappointing. The embedded biblical parallels and Christian symbolism, though, cannot be eliminated without destroying the whole of the story.

“‘I’ll send it to Bob Cratchit’s!’ whispered Scrooge, rubbing his hands, and splitting with a laugh. ‘He sha’n’t know who sends it’” (162). This act of the converted, reformed Scrooge connects directly to the portly gentlemen’s misunderstanding in the counting house in stave one. This time, though, Scrooge is heeding the advice of Matthew’s Gospel. “Take care not to perform righteous deeds in order that people may see them … When you give alms, do not blow a trumpet before you … Do not let your left hand know what your right is doing, so that your almsgiving may be secret. And your Father who sees in secret will repay you” (Matthew 6:1-4).

What is perhaps the most important of all Christian references in A Christmas Carol is also the shortest. A four-word clause in a longer sentence describing Scrooge’s post-conversion Christmas Day activities: “He went to church” (166). It is the single most important celebration of Christmas, the truest Christmastime event. A repentant sinner taught and formed by three spirits who were sent by his caring, noncorporeal, penitent guardian, Scrooge went to church.

Stave IV: A Story Steeped in Symbolism

The Christianity of Victorian London and the direct references to the faith throughout A Christmas Carol clearly demonstrate Dickens’ attention to Christian matters. He continues, though, to present Christianity in his story through symbolistic allusions to the New Testament and to liturgical rites.

The Holy Trinity—a triune God—is central to Christian belief. The celebration of Christ’s death and resurrection occurs in a triduum of Holy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday. And the number three presents itself frequently in sacred scripture. In Dickens’ devotion to the New Testament, particularly the Gospels, he would have been well aware of several occurrences of the triadic theme.

For example, “Mary remained with [Elizabeth] about three months and then returned to her home” (Luke 1:56).

Another instance: “Jesus said to Simon Peter, ‘Simon, son of John, do you love me more than these?’ He said to him, ‘Yes, Lord, you know that I love you.’ He said to him, ‘Feed my lambs.’ He then said to him a second time, ‘Simon, son of John, do you love me?’ He said to him, “Yes, Lord, you know that I love you.’ He said to him, ‘Tend my sheep.’ He said to him the third time, ‘Simon, son of John, do you love me?’ … He said to him, ‘Lord, you know everything; you know that I love you.’ Jesus said to him, “Feed my sheep’” (John 21:15-17). In the original Greek text, Jesus uses different words for love: agape, agape, philos. Still, he asks three times.

And a third: “Jesus said to [Peter], ‘Amen, I say to you, this very night before the cock crows, you will deny me three times’” (Matthew 26:34). These are but three examples of plentiful New-Testament threes.

How this relates to A Christmas Carol is through Dickens’ own use of the number three. The most obvious is represented by the three spirits who visit Scrooge on three nights. Three days to Scrooge’s conversion; three days to Christ’s resurrection. Of course, the spirits achieve their combined three days of work in one night. “‘It’s Christmas Day … I haven’t missed it. The Spirits have done it all in one night” (161). Three in one. A trinity.

Beyond the triad of spirits, the theme emerges subtly and overtly throughout the narrative. While Scrooge was busy in is frigid counting house on Christmas Eve, “the city clocks had only just gone three” (9). Later, after Marley’s visit, “Scrooge went to bed again, and thought, and thought, and thought it over and over and over, and could make nothing of it” (46). Finally, Fezziwig had three daughters (62) and three thieves visited Old Joe to sell items they had stolen from the deceased Scrooge (135). They did not cast lots for his vesture.

Richest in symbolism of the Angel of the Lord and of Christ Himself, is Scrooge’s first visitor as foretold by Jacob Marley. The Ghost of Christmas Past “wore a tunic of the purest white [and] from the crown of its head there sprung a bright clear jet of light” (48).

White clothing is a consistent theme in the Gospels and the Book of Revelation. “And he was transfigured before them, and his clothes became dazzling white, such as no fuller on earth could bleach them” (Mark 9:2-3). Later, after Christ’s death on the cross, a white tunic is prominent: “On entering the tomb they saw a young man sitting on the right side, clothed in a white robe, and they were utterly amazed” (Mark 16:5). Revelation equates white garb with victory evil and sin. “The victor will thus be dressed in white, and I will never erase his name from the book of life but will acknowledge his name in the presence of my Father and of his angels” (Revelation 3:5).

Perhaps the Ghost of Christmas Past was inspired by the angels and Christ. Maybe he is a simple symbol for Christ’s salvation. The spirit’s characteristic of light solidifies the divine representation. “‘Would you so soon put out, with worldly hands, the light I give?” the Ghost of Christmas Past queries Scrooge. “Is it not enough that you are one of those whose passions made this cap, and force me through whole trains of years to wear it low upon my brow!’” (50). Though sin hinders light, the salvation of Christ casts out darkness. “Jesus spoke to them again, saying, ‘I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will not walk in darkness, but will have the light of life’” (John 8:12).

The Sermon on the Mount: “You are the light of the world. A city set on a mountain cannot be hidden. Nor do they light a lamp and then put it under a bushel basket; it is set on a lampstand, where it gives light to all in the house. Just so, your light must shine before others, that they may see your good deeds and glorify your heavenly Father” (Matthew 5:14-16).

John the Apostle’s first letter to early Christians offers yet another connection to light. “God is light, and in him there is no darkness at all,” John writes. “If we walk in the light as he is in the light, then we have fellowship with one another, and the blood of his Son Jesus cleanses us from all sin” (1 John 1:5, 7).

The final symbolic references in A Christmas Carol come in the acts of the Ghost of Christmas Present. As he walks with Scrooge through the streets of London on Christmas Day, he blesses things and sprinkles people with water and incense. The Ghost of Christmas Present “stood with Scrooge beside him in a baker’s doorway, and taking off the covers as their bearers passed, sprinkled incense on their dinners from his torch” (92). “He smiled, and stopped to bless Bob Cratchit’s dwelling with the sprinkling of his torch.” (94). Blessing of food, use of incense, and sprinkling rites are among the most common and recognizable practices among Christians—even apparently those like Dickens whose liturgy and rite attendance was negligible.

Stave V: The End of It

Had Charles Dickens been an atheist or an agnostic or were simply resistant to including avoidable Christian elements in his story surrounding the twenty-fourth and twenty-fifth days of December, he could have. Films of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have done it all too often. Elf, The Santa Clause, and Scrooged—based upon A Christmas Carol—are only a few examples of so-called Christmas movies absent any specific Christian reference. Even the beloved Miracle on 34th Street, while argued by many to be an allegory of Christianity, leaves the religion itself out of the story entirely.

The popular 1989 farce, National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation, makes more references to Christianity than any of the above films. Still, each is considered a Christmas movie and takes place in the predominantly Christian United States on or about the twenty-fifth of December (Jones). It is worthy of note that all the movies just mentioned are on Entertainment Weekly’s list of the 20 best Christmas movies ever (Nashawaty).

So, while Christianity was engrained in 1843-English culture, its inclusion in A Christmas Carol had to be a choice. As demonstrated by the writers of the above contemporary films, an entertaining and/or amusing Christmastime story can be told without mentioning the Christianity of the high holiday. Dickens chose otherwise. He chose to craft a Christian tale, a good story, an engaging narrative that has thrived for nearly two centuries. In a truly Christian way, Scrooge’s experiences a conversion. From a self-interested miser favoring prisons and workhouses over social programs for the common good, he is reborn a selfless model of humility and anonymous generosity.

“It was always said of him, that he knew how to keep Christmas well, if any man alive possessed the knowledge” (170).

Works Cited

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol: A Ghost Story of Christmas. Chapman and Hall, 1843.

Dickens, Charles. The Life of Our Lord. Simon and Schuster, 1934.

Jones, Jeffrey M. “How Religious Are Americans?” Gallup, 23 December 2021.

Nashawaty, Chris. “These Are the 20 Best Christmas Movies Ever.” Entertainment Weekly, 28 November 2023.

The New American Bible, Revised Edition. Catholic World Press / World Bible Publishers, 1997.

Schlicke, Paul, editor. “Religion.” The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Charles Dickens. Oxford University Press, 1999.

Timko, Michael. “No Scrooge He: The Christianity of Charles Dickens.” America: The Jesuit Review, 22 December 2008.