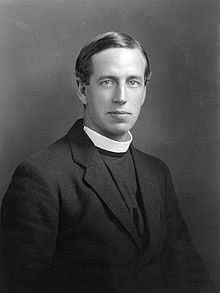

Monsignor Ronald Knox (1888-1957) is remembered as theologian, translator of the Latin Bible, author of detective stories, novelist, poet, and most of all as Catholic apologist. After a youthful career distinguishing himself with notable academic awards, at the age of 24 he was ordained an Anglican priest. Five years later, partly under the influence of G.K. Chesterton (at whose funeral Mass in 1936 Knox delivered a panegyric) he was received into the Catholic Church and a year later was ordained a Catholic priest. Upon his conversion, his father, the Anglican Bishop of Manchester, cut him out of his will.

An incident in 1926 is worth mentioning as evidence of Knox’s flair for the dramatic moment, a trait he shared with Chesterton. On one of his regular BBC radio broadcasts Knox produced the script for a simulated riot in London which included the murder of a government official and the destruction of both houses of Parliament. The program was punctuated by band music supposedly played from the Savoy Hotel. Since the Russian Revolution was barely ten years old, many people listening to the program panicked, supposing a full insurrection to be underway. Twelve years later Orson Welles produced his infamous radio broadcast of H.G. Wells’ novel War of the Worlds, also punctuated by sinister band music while the Martians were supposed to be invading the United States. This broadcast again sent Americans panicking into the countryside to escape the cities where the Martian invasion was supposedly concentrated. Welles later attributed his idea for the sensational program to Knox’s BBC production.

As one of his fans has put it, Knox writes constantly “with the zeal of a convert and the depth of a scholar.” His literary style is subtle, elegant, forceful, and hints at Chesterton’s influence, insofar as Knox also was adept at aphorisms. A few quotes will aptly demonstrate. “Hard hearts, not broken hearts, are the world’s tragedy.” “To be present when two other people are arguing is, almost always, to be in a state of impotent fury at their joint incompetence.” “If the hatred or contempt of men could kill the Catholic faith, it would have been dead long ago.” “The cross itself is a providentially appointed sign of contradiction … symbolic of the fact that Christianity and the world are perpetually at cross purposes.” “A scandal carries further than a tale of sanctity; our Blessed Lady lived and died unknown, but all of Jerusalem knew when Judas hanged himself.” “It is so stupid of modern civilization to have given up believing in the devil … he is the only explanation of it.”

The range of Knox’s theology and apologetics is vast. Here it must suffice to focus on just two issues that concerned him in order to get some measure of the man. The first issue ties in with Knox’s own conversion to the Church of Rome. In The Belief of Catholics (1927), perhaps his most popular book, there is a chapter titled “Where Protestantism Goes Wrong.” Speaking for Catholics, Knox says, “We derive from our apprehension of the living Christ the apprehension of a living Church; it is from the living Church that we take our guidance. Protestantism claims to takes its guidance from the living Christ. But what is the guidance he gives us, and where are we to find it? That is the question over which Protestantism has always failed to answer the Catholic challenge, over which it finds itself increasingly difficult, nowadays, to answer the challenge of its own children.”

Knox objects to the stereotypical way that Protestants think about Catholics; they falsely assume Catholics allow the Church to come between them and Christ. On the contrary, in every way possible Catholics know that their sanctification comes directly from Christ. The sacraments, though administered by the Church, are sanctified by Christ’s presence in them. The Church does not come between Christ and the soul, yet the Church does come between Christ and the mind, which is a different matter. Very simply, “It is through the Church that the Catholic finds out what he is to believe and why he is to believe it.” When Protestants say they opt to believe the Bible before they believe the Church, they seem to forget, or have never read, what Paul said in 1 Timothy 3:15: “The pillar and bulwark of truth is the Church.”

Except for the more conservative Anglicans of Knox’s day (C.S. Lewis, for example) Protestants in general have had little respect for the authority of the Church. They much prefer to view the Church as an intellectual figment rather than a historical fact. Sola scriptura (scripture only) became the war cry of the early Protestants since they realized that they could not attack the authority of the Catholic Church without a weapon, and there was no other weapon available but the Bible. Of course, the Church possessed the same weapon and was the first to use it when, by the authority of the Church in the fourth century, all the present books of the Bible were canonized without the help of Protestants. Over the long haul of history ever since, Protestantism has benefitted from the Catholic Church’s authority over the Bible, the same authority that Protestants now renounce. The inescapable conclusion to be drawn is that, after Luther and during all the wars of the Reformation, we have seen “the picture of blood flowing, fires blazing, and kingdoms changing hands for a century and a half, all in defense of a vicious circle.”

But as the modern world arrived even the authority of the Bible came to be suspect. Mainstream Protestantism began to question Genesis, II Peter, James, and other traditional sources of authority. “For three centuries the inspired Bible had been a handy stick to beat Catholics with; then it broke in the hand that wielded it, and Protestantism flung it languidly aside…. In our time we are beginning to reap the whirlwind. Even men of moderate opinions will not, today, vouch for the authenticity of the Fourth Gospel; will not quote the threefold invocation of Matthew 28:19….” Yet, where is their authority for doing so? It cannot be in the Bible and it cannot be in the Church. It rather must be in the individual opinion of the Protestant as he reads the Bible to suit himself. This is the logical consequence of self-styled democratic and modernist theology, the assumption that every Christian should believe his opinion is as good as anyone else’s, even when his opinion goes against the grain of ancient Christian teachings. If Knox lived today, he would be shocked at the progressive decline of Christian unity and principles not only within the Church of England, but also within the Church of Rome, as millions of Catholics join mainline Protestants in the endorsement of such radical notions as abortion-on-demand, same-sex marriage, and most shocking of all for them as Catholics, the repudiation by many of the Real Presence.

The fundamental error of Protestantism is that it leaves its followers without a final authority for interpreting the Bible. Different readers find different truths, so who is to adjudicate the real truth from the opposing views? Thus, from the very start with Luther’s rejection of absolute, unwavering and united authority lodged in the Church, Protestantism was doomed to fragment into thousands of sects, the very thing that Jesus and Paul preached against (John 10:16 and Ephesians 4:26). As Knox pointed out in Soft Garments, Protestants may well rejoin that conscience is the final guide and no other is needed. But this is not satisfactory, Knox answers. Different readers have different consciences and will read what they like into Scripture. As the Apostle Peter warned, they will do so “to their own destruction” (2 Peter 3:16).

Take, for example, the question of the existence and nature of hell. In the early days of Protestantism the assent to the traditional Catholic notion of hell was still prevalent. But as time wore on, more and more it became evident that liberal Protestant theologians were going to doubt the Catholic understanding of hell, and were going to regard that understanding as beneath the goodness of a loving and merciful God. But this shows precisely the Protestant dilemma. Contrary to their former stance of sola scriptura, now theologians are to supplant scripture as the ultimate authority. Jesus in Matthew 25 tells us in words that cannot be twisted beyond their meaning that Christ’s justice is as swift as his mercy. “Depart from me ye wicked, into the everlasting fire, which is prepared for the devil and his angels.” Thus, Knox concludes, mainstream Protestantism has broken down into its myriad forms of contradiction and subjectivism, and has ceased to be the Protestantism it started out to be. What indeed do Protestants think when they read words of scripture from the mouth of Jesus that he had founded his Church upon the rock of Peter, and that the gates of hell would not prevail against it? Have they never heard that Peter and his successors, guarding the Church against the gates of hell, have lived and worked faithfully for 20 centuries in the Church of Rome?

A second issue by which we may take the measure of Knox’s genius as theologian and apologist would be to distinguish between two vital ways of our getting to know God. As Knox put it in Proving God, “Man is called upon to serve God with his whole heart and his whole mind, not with a fifty-fifty amalgam of the two. The two faculties should, by rights, function together as smoothly as the two lobes of the brain. In practice they have to be stimulated alternatively, – and by a single process, because the recognition of our own inadequacy as creatures is at once the guarantee of God’s existence and the basis of all worship.”

This means that we must not have to choose between Thomas Aquinas and Blaise Pascal. We should not have to take the either/or position of arguing that God can be grasped either in the head or in the heart, but not both. Aquinas and Pascal insisted on the bilateral approach to God. Aquinas offered the famous “five proofs” to those who already believe in their hearts, but also to those who do not believe in their hearts that God exists. For atheists and agnostics the proofs are clearly intended to open a path to belief, if not conviction. “To one who has faith, no explanation is necessary. To one without faith, no explanation is possible,” said Aquinas. Faith must not arrive by willful consent of the intellect alone, for the intellect alone is fallible. The heart must simultaneously consent with the intellect. Aquinas believed with Augustine that the fundamental desire for human happiness is universal, but that this hunger can only be relieved by the heart’s desire for friendship with God.

This was also Pascal’s view, for he believed that atheists can dismiss the “five proofs” with a flick of the intellectual wrist, but they cannot so easily dismiss what he called the “reasons of the heart, reasons that reason cannot know.” That “reasoning of the heart” is achieved both through the will that naturally yearns for God, and the intuition that its yearning is justified. Intellectual comprehension of God’s existence is fruitful, and all the more so as it is a bridge to understanding why we yearn to know God. Moreover, it is required that we have a certain intellectual grasp of our faith if, as the apostle Peter advised, we should be able to give an account for it to those who might ask why we believe. But intellectual certitude varies, in the capacity to achieve it, from one person to another. Without being a Pascal or an Aquinas, the farmer in his fields can have as much faith, and certitude of his faith, as anyone else. He can have this faith just by the sheer act of submitting his will to what he perceives to be Gods’ will, as in the simple prayer “Thy will be done.” Faith, then, is God’s gift, and God gives not only faith, but also the certitude of faith, to all who are willing to receive it, because the origin of that faith as a gift is the One who cannot possibly intend to deceive. Thus conviction becomes absolute.

The certainty that comes with faith is not the kind of certainty demanded by the skeptic or the atheist. That kind of certainty concerns itself only with empirical realities that can be logically demonstrated, such as whether the sun revolves about the earth or the earth revolves about the sun. Having become infatuated with his conquest of nature through science, the skeptic cannot imagine any other approach to any other reality, or any so-called truth about any other reality. Thus, Knox argues, “Faith is the first duty of the Christian, and mystery is the food of faith…. You admit, not grudgingly, but with pride, that there are truths in the world too deep for your limited human understanding, and you salute them reverently as something out of your reach.” Such mysteries would include the Trinity, the Incarnation, and the Real Presence. To a hard-nosed skeptic such doctrines seem not improbable, but impossible. But this is only because the mind of the skeptic is finite and limits itself to human logic, whereas these mysteries come from a God whose powers are infinite in possibilities and surely beyond the reach of human understanding. The skeptic wants to know the mind of God, forgetting that this ambition is the original sin of Adam and Eve who wanted to know what God knew about the forbidden fruit. God is entitled to his secrets, and we are presumptuous in judging God because we do not understand them.

As Knox puts it, “You may picture human thought as a piece of solid rock, but with a crevice in it just here and there – the places, I mean, where we think and think and it just doesn’t add up. And the Christian mysteries are like tufts of blossom which seem to grow in those particular crevices, there and nowhere else.” The analogy is superb and could be extended indefinitely. For example, why does life in millions of types exist everywhere on the planet, but imagination and insight and creativity exist only in the hard rock of the human soul? A divine plan seems called for, whereas atheism would deny any such plan, but could offer no other explanation. Evolution by Natural Selection according to Darwin is certainly no answer to the mystery of human genius. Darwin himself could not see atheism as an answer to anything, and he denied he was an atheist even though many of his followers inexplicably followed that path and still do to this day.

The mysteries of religion satisfy a certain longing. They speak to our need for wonder and awe at the existence of everything, but especially our own unique selves. The pathways to God are many, and certainly not through the intellect alone. We, in the totality of our experience, will find God; or without that totality we will not find Him except (or perhaps not even) in the poor guise of a syllogism. This is why our imagination and our emotions are enlisted along with our reasoning to praise God and thank him in so many different ways (towering cathedrals, religious paintings and statuary, poetry, sacred music, etc.). This is why hymns holds us in thrall as no other kind of music can (and incidentally why there is no such thing as atheistic music). It is not uncommon to hear of the more serious doubters managing to get themselves into a pew at Christmas and Easter. The reaching out of God to everyone is ubiquitous. Indeed, many a hardened skeptic, upon first seeing his own just-born child, sees God’s hand at work in the child’s tiny fingers and gives thanks to the Almighty for the joy of beholding.

Let us end this brief profile of Knox by noting a prayer written by him shortly before his death as he was preparing yet another major writing project. Addressing God, he says, “I know well that in your sight every thought of the human mind is full of ignorance and misapprehensions. But some of us – and perhaps, at the root of our being, all of us – cannot forego that search for truth in which full satisfaction is denied us here. We apprehend that there is no encounter with reality, from without or from within, that does not echo with your footfall. We scrutinize the values, and can give no account of them except as a mask of the divine. Something of all these elusive things finds a place in my book. And you, who need nobody’s advice, can use anybody’s. So I would ask that, among all the millions of souls you cherish, some few, upon the occasion of reading it, may learn to understand you a little, and to love you much.”

Readers interested in critical studies of Ronald Knox might consult The Wine of Certitude by David Rooney and Ronald Knox as Apologist by Milton Walsh. Another valuable source is The Quotable Knox, A Topical Compendium of the Wit and Wisdom of Ronald Knox, edited by George J. Marlin et. al.