The medium is the message (Marshall McLuhan, 1964)

The invention of the digital world is supposed to be celebrated as a triumph of shared knowledge and digital access. On the surface, such a celebration feels deserved. An entire library now sits within reach even of a child’s pocket. Facts once buried in reference shelves now appear in seconds. Definitions, dates, summaries, and names flood the screen at the slightest provocation. Nevertheless, the Catholic intellectual tradition has always insisted upon a sober distinction that modern culture increasingly ignores, namely the difference between knowledge and wisdom. This distinction appears with clarity in the Catechism of the Catholic Church and receives its mature philosophical articulation in the work of Aristotle and Saint Thomas Aquinas. When that distinction collapses, the mind suffers, virtue weakens, and society follows along that downward slope with impressive speed.

The Catechism speaks of wisdom as a gift of the Holy Spirit that orders human knowledge toward God and the good life. Knowledge concerns the acquisition of facts, concepts, and information, while wisdom concerns judgment, orientation, and right use. Knowledge answers the question of what is known. Wisdom answers the question of how that knowledge ought to be ordered and toward what end it ought to serve. According to the Catechism, wisdom enables a person to see reality as God sees it, within a hierarchy of meaning that gives coherence to the whole of life. Knowledge alone lacks that ordering power. Without wisdom, information multiplies while understanding fragments.

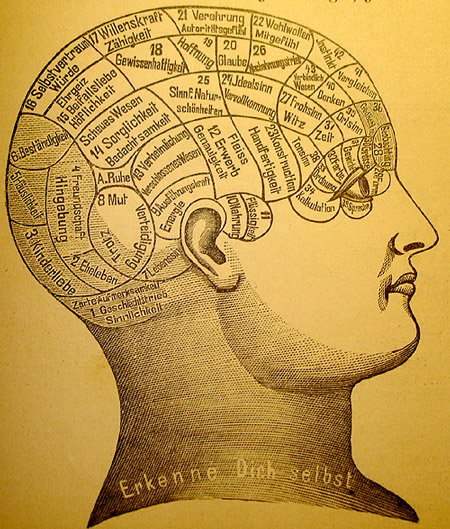

Saint Thomas Aquinas takes this distinction further in the Summa Theologiae by treating studiousness as a virtue and curiosity as a vice when left undisciplined. Studiousness concerns the right pursuit of knowledge according to reason and moral purpose. Curiosity, when detached from virtue, seeks knowledge for spectacle, novelty, domination, or pride. Aquinas describes curiosity as a disorder of the appetite for knowing, one that draws the intellect toward what distracts rather than what perfects. He warns that the intellect, like the body, can be harmed through excess. Knowledge pursued without measure corrodes the soul rather than forming it.

The digital revolution has accelerated this disorder beyond anything Aquinas could have imagined, even while diagnosing it with remarkable precision. The invention of the internet promised efficiency and access. Wikipedia promised democratized reference. Social media promised connection. Artificial intelligence now promises synthesis at scale. Each step has placed more information at human fingertips. Alongside this expansion has emerged a quiet assumption that possession of information constitutes entitlement. Modern man increasingly believes that he must know everything always and that any barrier to immediate access represents an injustice. This belief operates beneath conscious reflection and shapes habits of attention, expectation, and judgment.

Such an attitude damages the intellect because it treats the mind as a passive container rather than an active faculty ordered toward truth. The human intellect requires form, hierarchy, and rest. When bombarded without restraint, it loses the capacity for discernment. Information arrives faster than evaluation. Opinion replaces contemplation. Reaction replaces reflection. Under these conditions, wisdom starves while trivia thrives. The result appears everywhere in public discourse, where certainty grows alongside ignorance and volume replaces depth.

This dynamic explains why certain media figures and pundits flourish within the digital ecosystem. Their appeal too often does not rest primarily upon rigorous argumentation or intellectual discipline. Rather, it rests upon the promise of hidden knowledge. The suggestion that elites conceal secret truths flatters the restless curiosity of an audience trained to distrust authority while craving explanation. This pattern mirrors ancient Gnosticism, which promised salvation through secret insight rather than through moral conversion. The digital age has revived this impulse with algorithms rather than temples.

Psychology offers sobering confirmation of the harm caused by relentless information consumption. Studies on cognitive load demonstrate that the human brain performs poorly when overwhelmed with unfiltered data. Attention fragments. Memory weakens. Anxiety increases. Dopamine-driven novelty seeking trains the mind to crave stimulation rather than understanding. Sociology adds another layer by showing how information overload erodes trust within communities. When every claim competes for attention and verification becomes exhausting, people retreat into tribes defined by narrative rather than truth. Social cohesion fractures as shared standards of judgment disappear.

The Catholic tradition never opposed knowledge. On the contrary, it built universities, preserved texts, and cultivated intellectual excellence for centuries. What it opposed was disordered knowledge. Wisdom requires limits. It requires silence. It requires submission to truth rather than mastery over it. Saint Augustine warned that curiosity can become a lust of the eyes. Saint Thomas provided the moral framework to restrain it. The modern world has largely abandoned both warnings.

The discipline of the mind therefore becomes a moral obligation rather than a lifestyle preference. Natural law demands that human faculties operate according to their proper ends. The intellect exists for truth ordered toward the good. When treated as an instrument for endless consumption, it malfunctions. Theology deepens this claim by linking intellectual discipline to salvation itself. The way a person thinks shapes the way a person loves, chooses, and worships. Disordered thinking distorts moral judgment and weakens the capacity for repentance, humility, and obedience.

This truth became clear to me early in life through a simple practice. When I was about nine years old, I learned the mnemonic method known as the mind palace. It offered a way to organize information spatially and deliberately. I have used it ever since with consistent benefit. Over time, however, it became evident that technique alone could not provide ultimate coherence. It was Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas who supplied the deeper scaffolding. They provided categories of being, truth, thought, causality, virtue, and purpose that allowed every piece of information to find its rightful place. Without that framework, even the most elegant memory system collapses under its own weight.

Everyone categorizes what they learn. No mind escapes this task. Some categories expand through indulgence, while others shrink through neglect. These categories shape perception, speech, and moral development. A mind filled with outrage interprets every event as provocation. A mind filled with conspiracy interprets every silence as concealment. A mind filled with wisdom seeks proportion, patience, and truth. Over time, these habits form character. They either cultivate virtue or corrode it with disastrous outcome.

Wikipedia, social media, and artificial intelligence remain useful tools. Each serves legitimate purposes when governed by prudence. Problems arise when tools become masters. The guardian of the mind must learn to say enough. Curiosity must hear a command to cease. Information must yield to contemplation. The mind requires rest in order to function well. My friend Dr. Henry Russell once cautioned me that intellectual discipline includes the courage to disengage. Walking away restores proportion. Touching grass, as the saying goes, reconnects the intellect with embodied reality.

There exists more to life than the next plot twist, the next reveal, or the next viral claim. Eternal destiny unfolds through ordinary fidelity rather than spectacular discovery. Wisdom grows through silence, prayer, study, and restraint. Thinking about digital media, gratitude for access ought to be accompanied by repentance for excess. Knowledge remains valuable. Wisdom remains essential. The difference between the two determines whether the digital age forms saints or merely produces spectators.