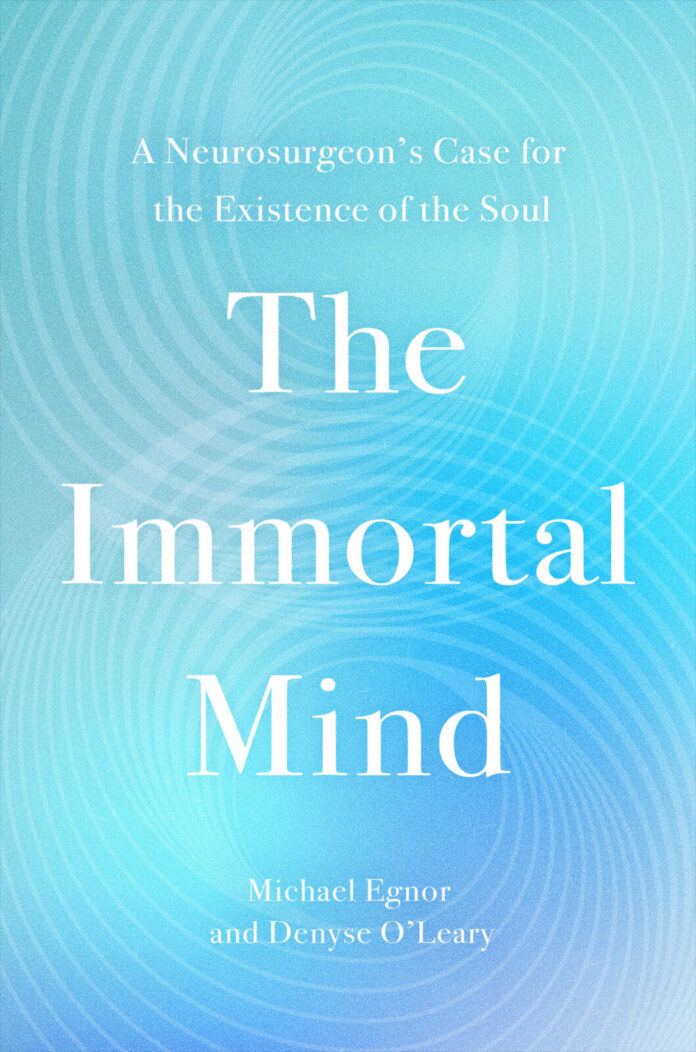

The Immortal Mind: A Neurosurgeon’s Case for the Existence of the Soul

by Michael Egnor and Denyse O’Leary

Worthy Publishers, New York, Nashville, June 2025

237 p.

The Immortal Mind is an intriguing book – a bit of a pot-pourri, traversing the gamut from Aristotle to Aquinas to the techniques and discoveries of neurosurgery, with a number of stops in-between. Written by Dr. Michael Egnor, a neurosurgeon with forty years’ experience cutting through cortices, and Denyse O’Leary, a science writer, The Immortal Mind offers a number of proofs for the immortality, or at least the transcendence, of the human mind (or soul).

We should clarify the term ‘proof’, for as the Catechism says of God’s existence, such may be proved, not in the sense of Euclidean axioms, but rather with ‘converging and convincing’ arguments, that together make the fact of a being such as God – or, here, the immaterial and immortal soul – beyond reasonable doubt, or perhaps at least reasonable.

The authors recount of a number of anecdotal cases that the mind has an operation that transcends the brain, signifying a mysterious connection between the mind and brain. Dr. Egnor begins with a vivid recounting of his own son’s apparent cure from what seemed severe autism, in response to a pleading prayer he made as an atheist in a Catholic chapel, which led to his own conversion.

This sets the stage for Dr. Egnor description patients who, after losing much of their brain through surgery or accident, but who still lived fully functional lives, with much of their ‘mind’ intact. These include patients with their corpus callosum cut (which allows the hemispheres to ‘speak’ to each other), and even those who have lost entire sections of cortical tissue.

Also recounted is the groundbreaking work of Montreal neurosurgeon Dr. Wilder Penfield (+1976), who in stimulating patients’ brains surgery (a necessary procedure so nothing vital is cut away), or when the brain is involuntarily excited during epileptic seizures, “evoke only movements, sensations, emotions or memories, but never reasoning or free will”. That is, there are no ‘arithmetic seizures’, ‘logic seizures’, or ‘Shakespeare seizures’. As the neurosurgeon concludes, “thought is a function of something other than and beyond the physical brain”. The will, abstract thought and voluntary actions, seem not to reside in the brain, but in something beyond, and not fully dependent upon it.

A section on near-death experiences (NDEs), which may be called in some sense after death experiences, in which patients can recount details of things outside their bodies, while clinically ‘dead’ on the operating table. (I’ve always wondered about these, and how real they be. After death, comes judgement, something that is not made fully explicit here).

And then there are the comatose, sometimes called human ‘vegetables’ (a term now eschewed), who were thought to have nothing going on inside. But many of those who did eventually ‘wake up’ claimed they could sense and think, even though their brains seemed asleep and non-functioning.

Added towards the end are some models of the mind, and a discourse on how the mind could not ‘evolve’, even if the body may have. Human minds are different in kind than whatever sort of ‘mind’ an animal may have. Empirical evidence supports this, although it’s difficult to prove definitively.

The book closes with some proofs for the existence of God, from creation, including Saint Thomas’ ‘five ways’ from his Summa, along with arguments that the computer, nor AI, could ever be a ‘mind’, as they cannot ‘transcend’ themselves (more on this in my own thought soon). Just so, a mind is not a computer, for, as we have just seen, unlike an algorithm, it does go beyond its own materiality.

All in all, this book is a fitting complement to the many theological and philosophical arguments for the existence of an immortal soul, and for a mind that uses the brain, may even need the brain, but transcends the brain, and goes beyond its materiality, even the brain’s existence.

Our Faith tells us this, for even though we may glean glimpses of immortality from reason (and science), it is still a difficult truth, as Saint Paul found out. Death still looms large in our thoughts, especially as we grow older or become mortally ill, and we need the strength and hope that God’s revelation gives us. In today’s reading, he confronts the Sadducees, who believed in neither the ‘resurrection, angel or spirit’, and there are many modern Sadducees, materialists to the core.

The Immortal Mind offers hope, that when our brains and bodies die, our minds and souls live on, immortally and forever. We just have to ensure that we live the right way here, so that we live the better way there.