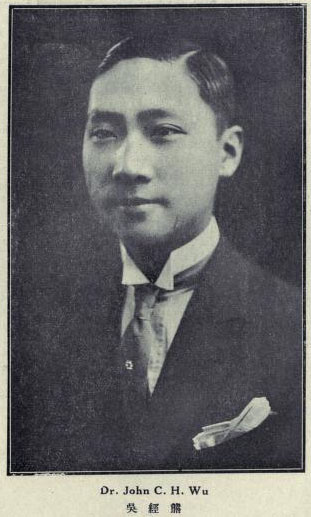

One of the most mysterious statements in all philosophy comes from the Taoist sage Lao Tzu, who proclaims in the Tao Teh Ching: “High virtue is not virtuous; therefore, it has virtue. Low virtue never loses its virtuousness; therefore, it has no virtue.”[1] At first glance, this saying appears so paradoxical as even to be nonsensical. According to the Chinese Catholic author John C. H. Wu, however, its true meaning is eminently reasonable and accords with one of the central insights of Christian mysticism.

Wu, a prominent diplomat and jurist of the Republic of China, was a student of Taoism before converting to Christianity. After joining the Catholic Church in 1937, he willingly admitted that the philosophy he previously subscribed to was “not unmixed with errors, and [inadequate] even where…not erroneous.”[2] Nonetheless, he retained a profound veneration for Lao Tzu and his fellow sages, whom he described as “scintillating stars…which should lead all peoples to the Divine Logos.”[3]

In a collection of essays titled Chinese Humanism and Christian Spirituality, republished by Angelico Press in 2017, Wu interprets Lao Tzu’s distinction between “high” and “low” virtue in light of the gospel. He writes: “What did [Lao Tzu] mean? Could he mean that high virtue is immoral? Certainly not! In saying that ‘high virtue is not virtuous,’ he merely meant that a man of true virtue is never self-righteous, as he would attribute his virtues to Heaven and to the operations of the Tao rather than to himself.”[4] (The ancient Chinese concepts of “Heaven” and “Tao” are roughly analogous to the Western concepts of God and the Eternal Law, defined by St. Thomas Aquinas as “the dictate of…Providence.”[5])

On this reading, the Tao Teh Ching bears a striking resemblance to the writings of Christian mystics. Both esteem humility and urge total reliance on the divine. Similarly, both censure moral self-righteousness, which makes out man, rather than God, to be the author of his own salvation. In this, they echo the words of Christ Himself, who railed against the Pharisees for “on the outside look[ing] righteous to others, but on the inside [being] full of hypocrisy and lawlessness.”[6]

The Christian perspective is unique, of course, for its emphasis on love. St. Paul writes: “If I give away all I have, and if I deliver my body to be burned, but have not love, I gain nothing.”[7] St. John of the Cross reminds us that “the value of good works, fasts, alms, penances, etc., is based, not upon the number or the quality of them, but upon the love of God which inspires…them.”[8] And St. Therese of Lisieux remarks, “Merit does not consist in doing or giving much, but in receiving, in loving much.”[9] Each of these statements is centered on the supernatural gift of charity, which Lao Tzu never addresses in so many words.

Still, Taoism and Christian mysticism agree on this: We, as creatures, cannot achieve perfection so much as allow the Creator to achieve perfection in us. Conversely, when we pride ourselves on our own moral goodness, we practice mere moralism, which is not ultimately meritorious and, insofar as it separates us from the divine, is actually dangerous.

And yet, Christians remain required to live morally upright lives. To quote St. James: “[M]an is justified by works and not by faith alone…. For as the body apart from the spirit is dead, so faith apart from works is dead.”[10] This raises the question: How do we know whether our good works derive from God’s grace or our own striving? When pursuing virtue, how do we know whether we are chasing the high or the low variety? The answer has as much to do with self-knowledge and spiritual discernment as it does with philosophy. Still, the sayings of Lao Tzu’s disciple Chuang Tzu, which paint a portrait of the man of high virtue, provide useful points of reference.

In the Book of Chuang Tzu, the eponymous Taoist describes the highly virtuous man as one who “acts differently from the vulgar crowd,” but takes no pleasure in his eccentricity, instead “conform[ing] as much as possible to the ways of the people.”[11] This suggests one characteristic of true holiness is the desire and willingness not to appear holy in the eyes of others. Meanwhile, by implication, those who insist on favorably differentiating themselves from their neighbors are like the Pharisee in the parable of the publican, who thanks God that he is “not like other men” and goes away unjustified because of it.[12]

Chuang Tzu identifies un-self-consciousness as another attribute of the highly virtuous. Wu paraphrases him thus: “Once you have attained a union with the Tao, humanity and justice [i.e. the moral virtues] will flow from you spontaneously like a stream from the fountain…; and in performing them you will feel no sense of being virtuous.”[13] This closely accords with the Catholic philosopher Dietrich von Hildebrand’s observation that “excessive self-observation” leads to pride, and that Christians should therefore obey God’s moral commands “[i]n holy self-forgetfulness…, according to the words of Christ: ‘Let not thy left hand know what thy right hand doeth.’”[14]

Finally, per Chuang Tzu, the highly virtuous man is knowable by his joyful attitude. He does not undertake moral actions as if they were, in Wu’s words, “onerous duties imposed…by an external authority or as a categorical imperative.”[15] Rather, the highly virtuous man does right cheerfully, with neither hesitation nor trepidation, and does not count the cost. This, too, accords with the insights of Christian mystics. The man Chuang Tzu describes would win praise from St. Paul, who writes that “[e]ach man must do as he has made up his mind, not reluctantly or under compulsion, for God loves a cheerful giver.”[16]

Modesty, un-self-consciousness, joy: Interpreting Taoism in light of the gospel, these are three marks of a morality derived from God, animated by the gift of His love, and meriting an eternal reward. To be sure, boldness, intentionality, and seriousness have roles to play in the spiritual life, and the Church is adamant that “human effort” may “dispose [one] for communion with divine love.”[17] But woe to those who mistake low for high virtue. The dangers of moral self-righteousness may not be far behind.

[1] Ch. 17.

[2] Chinese Humanism and Christian Spirituality, 159.

[3] Chinese Humanism and Christian Spirituality, 89.

[4] 111.

[5] ST I-II, q. 91, a. 1.

[6] Matt. 23:28.

[7] 1 Cor. 1:13.

[8] Ascent of Mt. Carmel, bk. 3, ch. 27, pt. 3.

[9] Collected Letters of St. Therese of Lisieux, 189.

[10] Jas. 2:24.

[11] Ch. 17.

[12] Lk. 18:11-14.

[13] Chinese Humanism and Christian Spirituality, 77.

[14] Transformation in Christ, 31-32.

[15] Chinese Humanism and Christian Spirituality, 77.

[16] 2 Cor. 9:7.

[17] CCC 1804.