On September 23rd, 1924, the universe got a little bigger – at least from our perspective. The ancients – Aristotle, Plato, Ptolemy – thought the cosmos more or less the size of our Solar System, stretching as far as Saturn, with a sphere of fixed stars rotating just beyond that. When modern telescopes were invented, first by Galileo in 1609 (based on a toy version by the Dutchman Hans Lippershey) astronomers eventually noticed that the stars were much, much farther away than had been thought. Distances began to be counted in light-years (the speed of light was first measured by Ole Romer in 1676) – how far light travels in one year, about 6 trillion miles, an unimaginably vast distance. Not only that: it was soon surmised – by Galileo, Kant and Herschel – that our own star, the Sun, is one of billions of stars in a galaxy we call the Milky Way, about 100,000 light years across.

So far, so vast. But on this day, nearly a century ago, the astronomer Edwin Hubble, a dashing, pipe-smoking all-American, who had been a star athlete – ha, ha – in college, playing football, baseball, basketball and running track – noticed as he peered through the 100-inch telescope at the Mount Wilson observatory in California, that one of the bright objects in the sky was not a star, but a whole new galaxy, the Andromeda Nebula, itself 2.5 million light years away.

Hubble eventually estimated there may be 2 billion such galaxies, although others now think perhaps 2 trillion, each one with billions of stars and separated by billions of light years. Hubble also discovered that these galaxies are moving away from each other at fantastic speeds, with greater velocity the farther they are from any given point (the so-called ‘Hubble’s Law’, which would provide evidence a few years later for Le Maitre’s theory of the ‘Big Bang’, but more on that later). For all we know there is no end to the universe, as space expands. (We will leave aside for now the question of other life forms, whether or not sentient, possibly inhabiting these countless planets)

Why? Why did God make a universe so big, that we would only realize its immense size in the twentieth century?

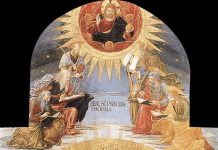

As the Catechism says, God created the world to manifest His glory to mankind, even if that remained partly hidden for aeons. After all, what else could show forth the nature of ‘God’ but an quasi-infinitely vast, measureless universe? The heavens are telling the glory of God.

As Saint Thomas puts it, in his own inimitable pithy way:

For He brought things into being in order that His goodness might be communicated to creatures, and be represented by them; and because His goodness could not be adequately represented by one creature alone, He produced many and diverse creatures, that what was wanting to one in the representation of the divine goodness might be supplied by another. For goodness, which in God is simple and uniform, in creatures is manifold and divided and hence the whole universe together participates the divine goodness more perfectly, and represents it better than any single creature whatever. (I.47.1)

All those galaxies, stars, planets, nebulae, for us, that we may wonder.

If this is the glory of this heaven and earth, the form of which is already passing away, how can we imagine what the next will be? Eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, the things which God hath prepared for those that love Him.

So fret not, dear reader. The Almighty has counted the hairs of your head, as well as the stars of heaven. You are worth more than many sparrows, and any number of galaxies.