Happiness is secured through virtue; it is a good attained by man’s own will. (Saint Thomas Aquinas)

What does it mean to be ‘virtuous’? There is virtue-signaling, with its pejorative sense, even though one might interpret it in a good way, with Christ’s exhortation to ‘let your light shine before men, and hide it not under a bushel basket’. Yet, in the Gospel on the day I write this, He also warns us to keep our virtue hidden, not allowing our left hand to know what our right is doing when giving alms, and praying and fasting in secret. Catholicism is filled with such (apparent) paradoxes, all of which lead to a deeper synthesis. For there is a time to be bold, and a time for discernment; a time to proclaim, and a time to hide.

The only way this paradox may be resolved is if we are truly virtuous and doing the ‘good’ that is based in that truth. Virtue signaling, the simulacrum of virtue, could be taken in the sense of showing forth our true virtue, when it should be hidden (boasting). In a more sinister way, it is showing a virtue that we do not have (hypocrisy). And in an even worse way, it is acting out a virtue that is not a virtue, and that we don’t even believe is a virtue, and may in reality a vice. Politicians who hobnob maskless and without social distancing, who scramble to don their face covering and stand apart for the cameras – yet not quite quickly enough. Or other ‘elites’ who make a big show defending the rights of women, then are caught in compromising positions with the same women, or even girls, using them to satiate their diminishing libidos. Or those who defend gender equality, yet vote down laws prohibiting gender-selective abortion. It gets worse, but we will leave it there, for now. What dead men’s bones lie behind our pro-abortion politicians may have to wait for the dies irae. And we should always remember, but for the grace of God…

Virtue – the real kind – requires that we dig deep, rooting out even our hidden faults which, if not so excised, will metastatize. Saint Philip Nero compared vices to weeds growing in a garden – they are all joined deep under the earth, and you think you’ve got them, when another springs up, oft where we might least expect it. A ‘nice’ garden with rotten soil, to paraphrase the Gospel, is not one that will last.

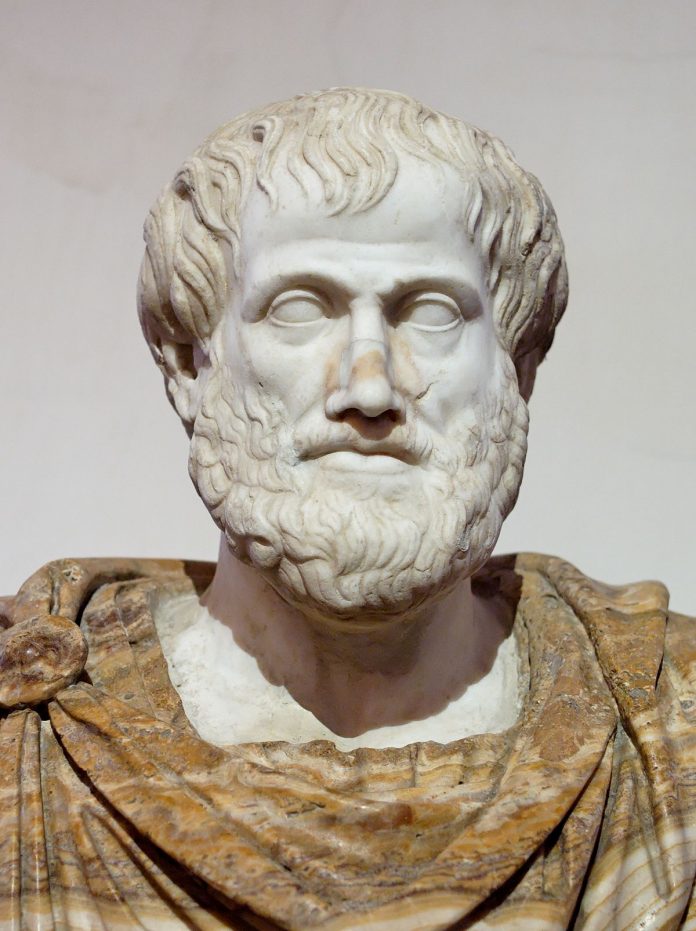

Which brings us back to virtue, versus signaling: I will leave you with two thoughts, from two great men, one far greater than the other, Aristotle and Christ. ‘The Philosopher’ – for so Saint Thomas called him – described virtue as a the ‘perfection of a power’, when some potency within us was brought to its full actualization, whether this be some athletic prowess, or intellectual endeavour. We are what we make ourselves to be by what we do.

These potencies are within and should fulfil our nature, and if anything contradicts that nature, it is by definition unvirtuous, or, as we might put it more vividly, vicious. This does not mean quite what most understand by this term, that only psychopathic serial killers are ‘vicious’. We are all so in some way, insofar as we act, and so become, contrary to our nature, which means contrary to how God made us. Witness the sad spectacle of ‘Caitlin’ Jenner, and what is worse, the confused teenagers who follow the septuagenarian’s scandal.

To fulfil and perfect ourselves, we follow the path of virtue – to be all that we can be, as an old commercial had it. There are virtues specific to each individual – we each have proclivities to music, academics, athletics, art- but there are general virtues that apply to all, the moral virtues especially. As mentioned in the last posting on truth, we naturally know what is in accord with our nature, and we must use our conscience to apply what we know to each situation in which we find ourselves. As Aristotle might put it, a virtuous act one that a virtuous man would do.

Those who try to make vice ‘natural’ are doing a vicious thing, and at some level, deep down, they know it. Hence, the use of force and violence, of coercion and censorship, in their petulance and bullying, and ultimately vain, attempt to call what is evil, good, and good, evil.

Aristotle got as far as one might get down the road of virtue without the benefit of Christ’s revelation, so was more or less confined to the horizons of this world. He saw that the greatest ‘thing’ we could do was to contemplate truth, and the greatest virtue was the wisdom derived therefrom. But this in the end is an earthly wisdom of the magnanimous man, with books, and servants at his command.

Christ offers us a ‘virtue’ that goes beyond this transitory and brief life, that even seems paradoxical from its perspective: Blessed are the sorrowful, the meek, the poor, the persecuted. Our Lord does not deny natural virtue, all those areas in which we perfect ourselves – after all, grace does build on nature – but these are not what are essential. What matters most is ‘where our heart is’, for there our treasure be also.

What Aristotle and Christ have in common is that virtue is interior: It was what we are, and not so much what we do, even if the latter flows from the former. There is no need to virtue-signal, for such virtue signals itself, in the abiding and eternal allure of the saints, which is how we might understand by allowing our light to shine before men.

While we our earthly gardens so they may bear fruit, may we be at least as diligent with those of our souls – root up those weeds, so that what is healthy and life-giving may thrive.

For by their fruits, ye shall know them.