. . . the rabbis said: “Solomon had three thousand parables to illustrate each and every verse [of Scripture], and a thousand and five interpretations for each and every parable”—which computes to a total of three million fifteen thousand interpretations for every scriptural verse.[1]

Suppose we were to apply this statement to the Gospel about the labourers called to work in the vineyard at intervals throughout the day.

- To begin with, one could apply the different summons to various moments of conversion, the earliest corresponding to cradle Catholics and the last to a death-bed conversion. In this reading, that everyone received the same wage would correspond to the fact that the faithful Christian and the repentant sinner receive essentially the same reward, namely, the beatific vision.

- A second interpretation might note that the men that worked the entire day were better off than those that stood “idle all day in the market place.” Which is to be preferred: someone with a secure job and assured income or someone out of work, with no prospect of earning anything to care for his family? Surely the former.

- Perhaps Jesus wants each of us to realize that he is the one taken on at five in the afternoon, and hour before closing time. We are “unprofitable servants”[2] but amply rewarded by a merciful God.

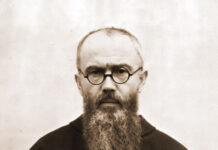

- Or, again, we could note that some move rapidly along the road to sanctity, covering in an hour ground that other require a whole day to achieve. Thus, we see that Thérèse of Lisieux, who died at twenty-four, is as great a saint as John Henry Newman, who lived to be eighty-nine.

- Could we read the parable as a precis of the history of salvation, with the hard-working labourers compared to the Christians of the first centuries, who were austere in practice and faithful in trials that we softies could hardly bear. Perhaps, as a time line suggests, the first hour corresponds to the Apostolic Church; the nine o’clock would be the patristic period; noon, the Middle Ages, three in the afternoon, today. The five o’clock would then represent the end of time, when the final reckoning will take place: the wages.

- I wonder, too, if there is not a trinitarian allusion, by which the owner of the vineyard would correspond to the Father, the foreman to the Son, and the mysterious growth of the vines to the presence of the Holy Spirit. Granting this, we could interpret the vineyard as creation as a whole. It has to be worked on man as a sub-creator commissioned by God who is to bring forth what lies latent in the physical world in the various civilizations that have flourished across history. The foreman calls upon others to help according to their various abilities.

- Another approach would be to see the vineyard as representing the Church, as Our Lord himself suggested: “The harvest is plentiful, but the labourers are few; pray therefore the Lord of the harvest to send out labourers into his harvest.”[3] The fact that the labourers are in a vineyard suggest the Eucharist, with the clergy as the workers providing the super-substantial bread and wine of salvation.

- Surely, too, the various times of day have their significance, as in the monastic schedule. The monks assemble to sing the divine office every three hours, with Lauds at dawn, terce at six, prime at nine, sext at noon, none at three and vespers at five. Saint Benedict, in his Rule that governs monastic way of life referred to the Office as “working for God,” Opus Dei, and the monk is encouraged to come to each hour as if he were beginning to pray for the first time.

- More imaginatively, I may consider all the workers as representing me, at various times of my life. I am hired at dawn, at the beginning of my life when I was baptized, with all the energy of a young child. But I am summoned anew at nine, corresponding to the enthusiasm of youth. Noon would point to another new start, my maturity, when I shoulder successfully the responsibilities of my state in life. Three p.m., then, could point to retirement and the final hour to old age and, at the end my death.

- I see that I have said nothing about the querulous workers who complained when latecomers received a full day’s wage. The Pharisees of the Gospels come to mind, in their continual carping at the words and deeds of Jesus. We must note, however, that they embody the temptation of everyone who practises virtue, for the temptation to spiritual pride is the most insidious of all sins, in that it corrupts the very actions that should produce holiness. If you are reading this, it may be that you, like me, have difficulty in admitting that someone, late in life, could have an equal, if not greater, commitment to and love for Christ as we do.

Here, then, are ten of the 4,015,000 possible readings of the parable; I leave you, at your leisure, to come up with the other 4,014,990.

[1] Gerald L. Bruns, “Midrash and Allegory: The Beginnings of Scriptural Interpretation,” in The Literary Guide to the Bible, edited by Robert Alter and Frank Kermode (Cambridge [MS]: Harvard University Press, 1987), p. 630.

[2] Lk 17.10

[3] Matt 9.37-38.