In the early morning hours of July 30th, 1945 – fifteen minutes after midnight, to be precise – in the last days of the World War, an American aircraft carrier, the U.S.S. Indianapolis, was struck by a torpedo from a Japanese submarine. Germany had already having surrendered the previous April, but the Asian theatre of the global conflict was still very much alive and well. The Japanese were not given to easy surrender, nor to the usual rules of warfare.

There were 1,195 men on board the massive ship, a floating fortress, but it went down in 12 minutes with 300 sailors to the bottom of the sea. (Her wreckage was found in August, 2017 at a depth of 18,000 feet, in a find financed by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen).

The other 890 were cast into the sea, with almost no lifejackets, lifeboats, drinking water, or food, and were not discovered until a passing reconnaissance plane happened to spot them four days later, by which time a majority had died of exposure, drowning, dehydration, exhaustion, killing each other in delirium or, most poignantly perhaps, by shark attacks. Surprisingly, 316 survived to tell the harrowing tale.

One of these is played fictionally by Robert Shaw in the first summer blockbuster, Jaws. In Captain Ahab-esque fashion, Shaw plays Quint, a veteran of the Indianapolis, now a local fisherman, who becomes obsessed with killing the Great White Shark of the film terrorizing the beaches of Cape Cod. But as they set out in his boat, the Orca, to search for the monster, he admist he never dons a lifejacket, since he’d rather drown than face what he saw happen to many of his mates floating in the salty brine, their dangling legs gnawed off by a myriad of razor-sharp teeth, screaming into the indifferent night of the sea. Well, if you’ve seen the film, you’ll know how that works out for poor old Quint. What comes around, goes around, and nemesis, in one sense, is getting what we might deserve, but may least expect.

A curious fact struck me about the true historical tragedy of the Indianapolis: Its mission was top-secret: to deliver the parts for the two nuclear bombs that would be dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki the following week, obliterating both cities, and incinerating nearly two hundred thousand men, women, and children instantly. I wrote a few years ago in Crisis of the evil of this, and am always mystified by the reaction of some – even Catholics who are otherwise ‘pro-life’ – who see not the patently proportionalist argument, that we had to kill myriads of women and children to stop even more bloodshed. I was disappointed that my piece was only published if another piece justifying the act was run alongside. And my essay was already in response to one in support of the bombings. Alas.

Almost none of the sailors on that doomed knew what they were delivering, but some of them did. The captain of the carrier, Charles McVay III, after being court-martialed, but later returned to service and exonerated, committed suicide in 1968 by gunshot, falling dead on his front lawn at the age of 70, clutching in his hand a small plastic toy sailor.

Sad. Prescinding from suicide and execution, most of us know neither the day nor the hour. Certainly the real sailors two decades earlier not know of the imminence of their own deaths. But, then, neither did the soon-to-be-incinerated citizens of those cities on those fateful August mornings.

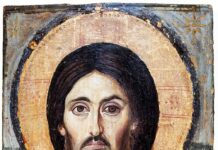

Is God saying something to us these tragedies, mysteriously linked in His providence? Were the victims like those crushed by the tower of Siloam, who did not deserve death, any more than any of us do?

Do you think that these Galileans were worse sinners than all the other Galileans, because they suffered in this way? No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all likewise perish. Or those eighteen on whom the tower in Siloam fell and killed them: do you think that they were worse offenders than all the others who lived in Jerusalem? No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all likewise perish. (Lk 13:2-5)

There is evil all around us, in the air, in the sea, but most of all, in our hearts. But when Christ speaks of ‘perishing’, He refers not primarily to our physical death – which will arrive in its due time, whether in a nuclear conflagration, as food for sharks, or, we may hope, in our own beds surrounded by family and friends. Rather, in His mercy, He is reminding us of the possibility of our spiritual death, which should be our primary concern, for far worse will our fate be if we cross that final Rubicon to eternity ill-prepared.

But hope, dear reader, for God wills our salvation far more than we do, and if we but live a sacramental life, persevering to the end in faith, hope and charity, great our reward will be. Only then can we face our end with joy.

And do not fear those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul; rather fear him who can destroy both soul and body in hell. (Mt 10:28)