Absence makes the heart grow fonder…

The proverb holds true in the main, but not, we must admit, always. There are many things, and we may admit, even people, we look back upon not with much affection. For the heart to grow fonder, it must begin with some fondness, in that holy absence, in the Song of Songs and Catherine of Siena sense, of longing for the Beloved, who has departed for a time.

Thus, we hope, we miss the Holy Mass, profoundly, deeply – I have even heard of grown men weeping, as we all should. At least, we miss our living presence thereat, for the Eucharist is still being said, but we laity make do as we might with ‘virtual’ Masses. There is much value in spiritual Communion – and the Church has a long history and tradition of such – but it is not the same as, and is no long-term substitute for, actual Communion, the very divine substance of His Body and Blood promised us by our Saviour – whose flesh is true food and whose blood is true drink, unto eternal life.

Thus, we may also hope that our appreciation of the Mass will be all the more fervent when, once again, the doors open again.

There is another sense of appreciation, or we may say, re-appreciation for the Mass, for what it really is, in a deeper sense. And, here, I refer to the priests themselves, celebrating behind those locked doors, all by their lonesome.

After all, ponder many of those pastors d’un certain age, steeped up to their collars in the mythical ‘spirit of Vatican II’, which has little to do with the actual teaching of the conciliar documents, a wraith which has stalked the land for the past half-century, prompting its oft-unsuspecting victims into liturgical aberrancies and idiocies, wreaking mayhem, a false spirit lamented by Pope Benedict XVI in his first Christmas address in 2005.

What have we lost in this present time of locked and empty churches? Do we miss the effervescent gathering that took up an hour each week, or the very core and centre of our existence?

Gone are the legions of Eucharistic ministers expediting Communion, the ad-libbing of the priest, turned towards the people, while turning the Mass, even subtly and unwittingly, into his own personal showtime; the choirs belting out what may in some sense be termed music, but hardly of the sacred and transcendent sort, with amplifiers, guitars and warbled, treacly ballads; the bored and listless congregation, checking their watches – or, now, their phones – warming up their cars before the Ite Missa Est, escaping, if they be quick enough off the mark, the final hymn…

Now, in all those vast, empty churches, all the priests must hear, with Simon and Garfunkel, is the blessed sound of silence…

The question presents itself: Does it now make sense to say Mass ‘facing the people’, when there are no longer any people to face?

Five decades after the controversial reform of the Mass under the hand of Annibale Cardinal Bugnini, what is the Holy Mass, and what do we miss?

For now, let us focus on the vast majority of priests who celebrate in the new rite, or what is more specifically the new use or order of Mass. I am rather confident that those priests who say Mass according to the 1962 Missal, in the universal allowance of Pope Benedict’s 2007 Summorum Pontificum already grasp what I am about to write, far more deeply than I do – for they live and pray it more than I.

We may hope – there is much hope in this current Covid crisis, if we look closely enough, and are receptive to what God may be telling us – that those priests who may have forgotten, even in some practical way, what the Mass is, and what the Mass is not: a secular community celebration, a get-together, a boisterous hymn-sing, or some sort of glee club to life one’s emotional doldrums.

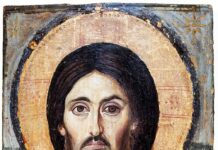

What the Mass is, at one level, is a sacrament, making present the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ under the species of bread and wine, but even this great miracle, the supersubstantial (epiousios) food promised by Christ in the Our Father and in Chapter 6 of Saint John to feed us as food for eternal life, is not the primary aspect of the Mass itself.

But at its deepest level, the Mass is a Sacrifice, the humanity of Christ offered to God the Father in His expiatory Passion and Death, one to end all sacrifices, after which no other sacrifices are needed, except our own participation in that one Sacrifice, and our reception of its fruits. Each and every Mass, even those said by the most humdrum, complacent priests, pours uncounted graces upon the world. It is this sacrifice that is re- presented in each and every Mass, even those said by a priest all by his lonesome, as private a Mass as one can get – for normally, a server is required, or at least highly recommended. But, again, in some dioceses, even servers seem not to be allowed. Strange times.

Regardless of what else ‘happens’ at Mass – all the accidentals surrounding the Sacrifice, be they good or bad, helpful or detrimental – that sacrifice is still present, consummated by the priest consuming the sacred species, for only he must receive. An ironic new clericalism, one might think, for now only priests get to attend Mass. But we can take what we might, and the grace therefrom.

It is for this reason that priests are strongly (enixe, in Latin) urged to say Mass every day, even sine populo, and I hope they all are, behind those locked doors.

And we may hope this time of our own fasting from the Eucharist – a punishment, we may take it, for our sins, and those of our nation, a veritable divine interdict, attenuated in that Mass itself is still being said – moves us to appreciate what we have now lost, for a time, and perhaps half a time.

As well, may we all, priests and laity, be given eyes to see and ears to hear, so that when those barred doors are burst open, the priest, with the joyous fervour of a converted Scrooge, skipping and crying out, ‘I have seen the light! – it is a Sacrifice!’. And when we all gather again – and not in the Haugen sense – we may wonder anew at the mystery, said facing God ad orientem, the priest leading his people, feeding them with his own hands, even if it takes a few more precious minutes, the chants and polyphonies once again restored, the mystery of what the Mass truly is may shine forth in full liturgical splendour…

We may always hope, even against hope.