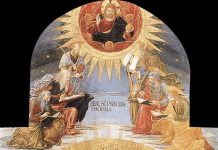

The Transfiguration is celebrated twice in the Church’s liturgy: on the second Sunday of Lent but also on 6 August. The latter date is significant in that it’s the anniversary of the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima in 1945, an event that hastened the end of the Second World War. The difference between the two can be demonstrated by noting Saint Peter’s words, “Lord, it is good for us to be here.” Nobody, but nobody, in Hiroshima would have said that! An examination of the two events is instructive, especially during Lent, when we respond more intensely to the call to repentance than at other seasons of the Church year. To begin with, the Transfiguration reveals God, while the bomb hides him. In one we see man at his best, in the other at his worse. The one edifies, the other scandalizes. Both experiences were brief, but with long-lasting effects: the disciples were strengthened for a life-long commitment to Jesus, to the preaching of the Gospel and to eventual martyrdom; the explosions at Hiroshima and Nagasaki left the (relatively few) survivors physically and emotionally shattered and the whole area devastated, dangerously radioactive for years afterwards. But the most telling is the contrast between the passivity of the Apostles and the initiative of the bombers. Peter, James and John were given a vision of the glorified Christ, something that they could perceive but not one that they could have merited, much less contrived on their own. But the bomb, no gift from heaven, was a weapon of destruction created by scientists and deliberately employed by the military. Their motivation may have been mixed—it did end the war—but it would be naïve not to recognize an element of what I may paradoxically term a destructive glee. Those of you who have seen the movie Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb will remember the scene in which one of the airmen jumps on the bomb and, hollering like a cowboy on a bronco, rides it down to its catastrophic destination. What a man cannot create, he can certainly destroy and can do so with a grim sense of accomplishment.

What, you may well ask, has this to do with us? Lent reminds us that each of us carries within himself the alternatives that we have been considering, viz., an intuition of what is supremely good and an inclination towards destroying that good. The former is identified as virtue, the latter as sin. The effects of our bad actions are hardly comparable to a nuclear attack, but we must not be misled to dismissing them as trivial. Isn’t disregarding, even denying the reality of sin a mark of our times? Lying hardly seems seriously wrong when everybody does it: politicians, entertainers, advertisers, the media. And yet Jesus identified Satan as “the father of lies.”[1] Infidelity and other irregular arrangements are now taken for granted to the point that they, not traditional marriage, have become the norm. Human life, once regarded as sacred, is more and more at risk as our governments and medical professions push aside the ethical principles that protected the unborn, the aged and the chronically ill. We are men and women alive in the present time and, as such, cannot but be affected by the moral atmosphere that we take in as unconsciously as the air we breathe. I do not mean to say that there are no moral imperatives generally honoured in Canada today, but they too are in the air and accepted as axiomatic: the need for a viable ecology—“saving the planet” as we say—for respecting aboriginal treaties and especially for honouring an almost limitless individual freedom.

If we are to maintain our Christian identity in an antipathetic world, we must have access of some sort to the vision of the transfigured Christ that the Apostles enjoyed on Mount Tabor. How is this to be accomplished? We must begin by purifying ourselves with the discipline of Lent. And if Lent recommends a turning aside from even legitimate pleasures, how much more does it require us to repent of those sins that have become so habitual that we are hardly aware of them. “The Lord loves righteousness and justice”[2] as the Psalmist reminded us, and we shall not encounter him until we gain the righteousness that he loves. Only then will our vision be purified so that we can recognize what is actually present to us. I can provide an instance of what I mean, from the autobiography of Alan Griffiths in which he records an event that took place when he was a schoolboy in the 1920s.

One day during my last term at school I walked out alone in the evening and heard the birds singing in that full chorus of song, which can only be heard at that time of the year at dawn or at sunset. I remember now the shock of surprise with which the sound broke on my ears. It seemed to me that I had never heard the birds singing before and I wondered whether they sang like this all the year round and I had never noticed it. As I walked on. I came upon some hawthorn trees in full bloom and again I thought that I had never seen such a sight or experienced such sweetness before. If I had been brought suddenly among the trees of the Garden of Paradise and heard a choir of angels singing I could not have been more surprised. I came then to where the sun was setting over the playing fields. A lark rose suddenly from the ground beside the tree where I was standing and poured out its song above my head, and then sank still singing to rest. Everything then grew still as the sunset faded and the veil of dusk began to cover the earth. I remember now the feeling of awe which came over me. I felt inclined to kneel on the ground, as though I had been standing in the presence of an angel; and I hardly dared to look on the face of the sky, because it seemed as though it was but a veil before the face of God.[3]

Not surprisingly, he later entered the Church, became a Benedictine monk at Prinknash Abbey in England and ended his life—he died in 1993—in India. Such wonders surround us everywhere. I once read a book about the complexity of human digestion that left me gasping with amazement. And the cosmos – all the stars, galaxies, planets – is unimaginably large and complex. How does it happen that we can know anything about it? And atoms, which are already inconceivably small, break into particles that seem to shrink almost into nothingness. Add to these aspects of the physical world, instances of human achievement in the arts, in technology, and in personal relationships, and you have the basis of conversion that can work in your life as the experience of young Allan Griffiths functioned in his or as the Transfiguration did for Peter, James and John. From this starting point we are enabled to enter that narrow and difficult path that leads to life[4] progressing beyond mere wonderment to the source of these wonders, i.e., to God, and then further to Jesus as the revelation of God: “He who as seen me has seen the Father.”[5] Thus, repentance gives way to spiritual growth, and—lo and behold—we have a generation of saints.a

[1] Jn 8.44.

[2] Ps 32/33.5.

[3] Bede Griffiths, The Golden String.

[4] Cf. Matt 7.14.

[5] Jn 14.9.