Is it the canary in the coal-mine, or the bull in an economic china shop? The closure of the Oshawa GM manufacturing plant – which has been making cars since just after the Second World War in 1953 – will put nearly 3000 people out of high-paying work, all them soon to be pounding the pavement, or going on the dole. But I’m going to try to see the good side of this.

The writing was on the wall, for a scant 15 years ago, the plant – there were in fact three, now down to one – was producing a million cars a year; that was reduced two hundred thousand and now, like the nursery rhyme about monkeys on the bed, there will be soon be none; and all this, after GM – a private company making private cars – was bailed out in 2009 to the tune of 7.23 billion by the federal government and 3.6 billion from the provincial. Ten billion pays for a lot of cars, one would think, but I suppose GM has burned through that mountain of taxpayer cash, so off they go to greener pastures.

The vast complex after 2019 will be left to decay into a cavernous ruin, eventually demolished, and commuters on the 407 – in their Mexican-made vehicles, one might presume – will soon drive by a weed-infested, barren, semi-concrete wasteland, like those that dot the rust-belt of America, symbols of what our economy is really like behind all the government glitz, and the shape of things to come.

The vast complex after 2019 will be left to decay into a cavernous ruin, eventually demolished, and commuters on the 407 – in their Mexican-made vehicles, one might presume – will soon drive by a weed-infested, barren, semi-concrete wasteland, like those that dot the rust-belt of America, symbols of what our economy is really like behind all the government glitz, and the shape of things to come.

As the pundits say, the effects of this will reverberate, like ripples through a swamp, which may soon be what Oshawa real estate is worth. GM claims that it wants to put its focus on other things, like electric and autonomous driving vehicles, along with other factors, such as ‘changing technology’, which means not just automated cars, but automated factories: For the future is in artificial intelligence (an oxymoron, but we’ll concede the point for now). Machines making machines makes more sense from the point of view of profit, for a robot can work faster, longer and more efficiently than any human, nay, than any ten humans.

And, once built, they need not be paid; there are no uppity unions with which to deal, no overtime, no benefits, no sick days and, what is perhaps best of all, no pensions; GM is paying out untold billions for baby boomer employees during the golden-lunchbox years to spend their golden years lazing around cottages. Those days are gone, perhaps for good, and now the fat must be trimmed.

It will take some time for the manufacturing of things as complex as cars to become fully automated – consider for a moment that the verb, manu-facto ‘made by hand’, may soon be obsolete. In the interim, GM and others global corporations will strive to reduce costs and maximize profits. To put things mildly, after two decades of Liberal ideological imprudence, from McGuinty to Wynne, Ontario is not the place for businesses to make money, unless you’re fleecing the government. Exorbitant water and energy costs – the results of the Green Energy Act – along with worker demands – not all of them unjust, mind you – prompt the relocation to places like Mexico and China, where the workers are treated even more like machines – slaves if you will. Of course, they don’t call it that, for workers line up to apply, just so they can make about one-fifteenth of a worker in Oshawa, from two to about four dollar per hour. And one wonders why GM, along with any number of other companies, takes the money and runs.

In China, things are even worse – no one really knows what is really behind the lies of the Communist Potemkin façade – living in cramped on-site in cubicles. But at least they can work and eat, even if, to paraphrase the lament, They’ve sold their soul to the company store. As an aside, I just heard that McDonalds, amongst other companies, has taken this to a new level, their uniforms made by prisoners in America, whom they can pay almost nothing, and revolt or striking out of the question.

Is this the future? Henry Ford perfected – if such be the verb – the mass production business model with his model-T, the first rolling off the assembly line on October 1st,1908. Frustrated with the initial slow pace of manufacturing – there were only eleven cars made in the first month – Ford hired ‘efficiency expert’ Frederick Taylor, a professional golfer and tennis player, who would watch and time the most minute motion of workers, so they could become perfect in at least one part of the ’84 areas of production’ required to build the car. Soon, the time it took to put the T together dropped from twelve hours to 93 minutes. By 1925, the Ford company was making up to 10,000 cars per month.

But at what cost? Workers were essentially considered an extension of the machines on which they worked, and inefficiency was punished. Ford began to spy on his workers to ferret out any ‘problems’ – from incipient alcoholism to marital difficulties – that would make them less effective workers. Robots don’t have those problems, at least, not yet.

But at what cost? Workers were essentially considered an extension of the machines on which they worked, and inefficiency was punished. Ford began to spy on his workers to ferret out any ‘problems’ – from incipient alcoholism to marital difficulties – that would make them less effective workers. Robots don’t have those problems, at least, not yet.

Henry Ford wanted his employees to make enough of a wage so they could own one of the cars they made, but that is now make this impossible, at least in Mexico, where workers just laugh when asked if they will ever own one of the luxury Audis they slap together; the same may soon be said of the once-lush land of Ontario.

We’re reaching the nadir point of this trajectory with the legions of Amazon workers, claiming – yes, you guessed it – that ‘they are not robots’. Really? In the minds of Bezos and his shareholders, they more or less are, and the more productive, the better. Peruse this article for one amongst many describing the abysmal, depressing, atomized labour conditions, with pedometers measuring every step they make.

Pope John Paul II warned of all of this, back in 1981 in his encyclical Laborem Exercens, that men would soon not only be chained to the ‘means of production’, but eventually overtaken by them. As the Holy Father puts it, there is nothing wrong with machines, per se:

Understood as a whole set of instruments which man uses in his work, technology is undoubtedly man’s ally. It facilitates his work, perfects, accelerates and augments it. It leads to an increase in the quantity of things produced by work, and in many cases improves their quality.

But as he goes on to caution:

However, it is also a fact that, in some instances, technology can cease to be man’s ally and become almost his enemy, as when the mechanization of work “supplants” him, taking away all personal satisfaction and the incentive to creativity and responsibility, when it deprives many workers of their previous employment, or when, through exalting the machine, it reduces man to the status of its slave.

Aristotle claimed that most men natural slaves, wanting someone to ‘take care of them’, to be provided that ‘good job’, any job, really, so long as they get their panem et circenses, their bread and circuses with which Nero placated the populace, even if it means being chained to a machine, plodding away at factory work, only to drive home through the desultory suburbs to fall asleep watching the endless dredge on Netflix.

It is fortunate and good news indeed that in the Christian dispensation, we have been set free, for we can – and must – resist this natural tendency to inertness and passivity with a deep reserve of energy which only a spiritual life, a strong will, a magnanimous soul, can offer. We must, as Leo XIII exhorted, become provident for ourselves and for those dependent upon us.

For that, we have to make some difficult and courageous decisions, about what it means to work, to ‘consume’ and what it is we really ‘need’. The reason Jeff Bezos is a multi-billionaire – some say the richest man who has ever lived, giving even the Pharaohs a run for their money – is because we love to buy the stuff he sells, quick, cheap, delivered right to your door, soon by flying drones, and made mostly by functional slaves, in nations that smirk at the notion of a living wage and workers’ rights.

Are we reaping the whirlwind we have sown? People are wringing their hands, and the anxiety is palpable. I heard one ‘employment outreach officer’ suggest – as she flailed for ideas on the CBC – that these workers, many of them well into middle age, might seek employment in up-and-coming marijuana grow-ops. Is this what we are now reduced to in this benighted nation?

My advice? Take these plant closures – as painful as they are, there are likely a lot more to come – as a blessing in disguise, or at least an opportunity to ponder anew what ‘work’ really means – that profit and efficiency are not the only criteria in economic decisions, and that work is for man, and not man for work.

There is also the far more fundamental personal element, that the worker should be able to see and participate in the fruit and value of his labour, to impress his personality on what he produces, whether that be something made by hand, or intellectual work. For the ultimate purpose of work is that we perfect ourselves most of all.

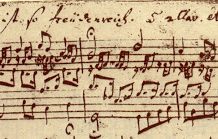

A final word, for now: As the great Thomist Josef Pieper put it, the whole purpose of servile labour is so that we might enjoy ‘leisure’, which is not lazy inertness, but rather that time and space to contemplate the higher things, to read, play music, converse, reflect and, most of all, worship God. As I quoted Solzhenitsyn the other day, the only place we have to go is up, with our end and purpose firmly fixed in heaven.

Of course, until we get there, we cannot just wander around discussing philosophy all day in the agora, and work must be done to put food on the table, something the Oshawa workers have to face, who have mortgages and minivans and, like most Canadians, probably a mountain of debt. But, first, food, for as someone once infallibly said, let him who does not work, not eat.

So before you consider me an impossible idealist, I do agree with Saint Paul, and will soon follow up with another reflection on wealth – and how we might capitalize, as the saying goes, on what little there seems to be left of it here. For there is always more than meets the eye, from God’s perspective.