When once a certain class of people has been placed by temporal and spiritual authorities outside the ranks of those whose life has value, then nothing comes more naturally to men than murder. —Simone Weil

To the great sweeps of history, there is always a witness with eyes and a heart committed to the truth, however horrific.

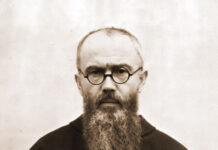

Alexandr Solzhenitsyn was one of these.

When the Soviet writer and dissident was born on December 11, 1918, the First World War had ended exactly a month before. And his homeland was bleeding to death from the civil war triggered a year earlier by Lenin’s Bolsheviks. It was a civil war unparalleled in history, one that would imprison Russia for decades and shape the rest of the 20th century. And one that would span the entire life of this infant who would one day become internationally famous for his unparalleled witness to the horrors of the Soviet state and the Gulag – Stalin’s system of slave labour camps. And for his immense literary talent and the suffering he endured from Soviet communism, from cancer, from ricin poisoning and finally exile.

Next month marks the centenary of his birth.

Born in the shadow of war

Born in the spa city of Kislovodsk, in the northern caucasus of Russia in the shadow of the Great War and the Bolshevik Revolution, Solzhenitsyn was considered a child prodigy, brilliant at mathematics, and devoted to literature in his spare time.

When World War II broke out, he became an elite artillery officer, but was arrested in 1945 after letters to a friend, in which he was critical of Stalin, were intercepted by counter-intelligence, leading to an eight-year sentence in the Gulag. This is where he began to commit to memory and to mental poetry everything he saw.

Upon his release, Solzhenitsyn became a maths teacher in a provincial town. He also began to write in earnest, ultimately producing a body of work that stood as a permanent indictment of Stalinism and communism. It still does.

Solzhenitsyn’s work was also a monument to the lives of the millions of his fellow countrymen who passed through the camps between 1930 and the mid-1950s. Men whose miseries were known only to fellow inmates and to God, and whose graves are marked only with numbers.

Even so, the world was moving on, and by the mid-1950s these slave labour camps had fallen into disfavour and were providing grist for what became the 1956 “secret speech” in which the new Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, denounced Stalin and promoted what was called a political “thaw” in Soviet life.

But was it really a thaw? Had the evil nature of communism – epitomized by Lenin – really changed? Were the mass executions ordered by Lenin as early as January 1918 against his enemies – whom he called ‘insects’ and who compelled his various agencies and secret police (the Cheka) ‘to purge the Russian land’ of homeowners, teachers, choir members, priests, monks, nuns, Tolstoyan pacifists, trade union officials and so on – mere history, mere statistics, best forgotten?

Into the maw of history

In history, new pages are not so easily turned, notes historian Paul Johnson: “Once Lenin abolished the idea of personal guilt, and started to ‘exterminate’ (a word he frequently employed) whole classes merely on account of occupation or parentage, there was no limit to which this deadly principle might be carried.”

Indeed, Lenin’s deadly principle unleashed a non-stop stream of carnage the world had never before witnessed. It led to the highest body count – estimated to be somewhere between 100-200 million corpses – of the 20th century, confirming for all time the true nature of atheistic communism and its seductive understudy – socialism – which Solzhenitsyn also condemned with all his courage and might.

He would know because he experienced it all. First hand. Then he wrote it down.

By 1930, the family property had been turned into a collective farm. And by 1936, at barely 18, Solzhenitsyn had already begun developing his epic work charting World War I and the Russian Revolution. This eventually morphed into his trilogy known as The Red Wheel, which begins with Book I, August 1914. At the same time, Solzhenitsyn was also studying mathematics at Rostov State University and taking correspondence courses from the Moscow Institute of Philosophy, Literature and History. In those days, however, he was not yet questioning the state ideology of Lenin, now being imposed by his successor, Josef Stalin.

That questioning came with his internment in the camps which formed within him the mental and moral grist for his greatest writing, beginning with his first novel, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovitch. Published in 1962, this short novel evokes a single day in the 10,000-day sentence of a Gulag prisoner. It was a sensation. And it led, two years later, to a renewed clampdown by the new Soviet leader, Leonid Brezhnev.

Solzhenitsyn’s next two novels were Cancer Ward, based on his bout with cancer as a prisoner, and distributed in Russia in 1966 in samizdat and banned the following year, before appearing in the European press in 1968. And The First Circle, describing life in a camp for technical specialists, won him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970.

Solzhenitsyn was becoming politically embarrassing. So much so, that the KGB (descendant of the Cheka) attempted to rid the country of him by poisoning him with ricin in 1972, though he survived.

That same year, the KGB also forced one of Solzhenitsyn’s friends to reveal where he had buried a copy of his great historical work, The Gulag Archipelago, his devastating account of what those concentration camps meant for 220 of the inmates. The book proved too much for the Soviet leadership which viewed it as a ‘cynical attempt’ to demonstrate that Lenin had led directly to Stalin, and that the camps flowed directly from Marxist ideology and were present in embryo from the first days of the revolution.

Exile

This led to Solzhenitsyn’s expulsion from the U.S.S.R. in 1974 and into exile in the U.S.

Sadly, the Soviet bosses’ thunderous denial of simple logic and irrefutable facts was not confined to the U.S.S.R. It continues to this very day among fashionable western intellectuals with minds fogged by ideology and who still dismiss Solzhenitsyn as a well-meaning but hopeless religious fanatic, a nationalist, a friend of the “Far Right” and a failed political prophet such as Dostoevsky and Tolstoy before him. And his writing as, get this, superficial!

Solzhenitsyn’s crimes? Apart from telling the truth about Soviet mass murder and its almost inconceivable cruelty? Well, he backed the U.S. war in Vietnam and criticized the American Left as traitors to the Vietnamese and Cambodians who were, as a result, slaughtered by the very communists the U.S. was fighting while under heavy leftist opposition at home.

He also criticized abject democracy – known to many as mob rule – for all the right reasons, supported General Franco in Spain and generally remained a chronic craw in the Soviet throat. Naturally, the Socialist Worker denounced him too as a bizarre religious fanatic though it conceded he was a talented writer.

A World Split Apart

Yet rarely had the presumptions of the elitist class been challenged as it was in June 1978 when, having spent four years in the U.S. in exile and nearing his 60th birthday, Solzhenitsyn delivered his now famous address to Harvard.

Titled A World Split Apart, his address was full of uncomfortable truths. He dissected the growing weaknesses and rising banality of the West which, he warned, was in far greater danger than it imagined. And for several reasons which included a free but utterly irresponsible press; a culture so soft as to be unhealthy and so devoid of suffering as to breed flat, superficial and uninteresting personalities with perpetually sunny faces. “What’s all the joy about?” he asked.

Not flattering. Instead, Solzhenitsyn’s speech was a stumbling block and a rallying cry that continues to this day because of its unflinching truths and his ringing predictions, such as the rise of nationalism in the U.S. “Many of you have already found out,” Solzhenitsyn said in his opening, “and others will find out in the course of their lives that truth eludes us as soon as our concentration begins to flag, all the while leaving the illusion that we are continuing to pursue it. This is the source of much discord. Also, truth seldom is sweet; it is almost invariably bitter. A measure of truth is included in my speech today.”

Yet Solzhenitsyn offered his bitter cup of truth “as a friend, not as an adversary.” So it was easy to understand why those who believe in the absolute sovereignty of man, not God, in the supremacy of socialism, and in the imagined ‘disappearance of evil’ found the truth too unpalatable to even consider. After all, his listeners were not only the graduates sitting before him, but the intellectuals, elites, and journalists of America.

Five Propositions

So no surprise that as Solzhenitsyn laid out the foundations of a world perilously “split” – culturally, economically and philosophically – they didn’t much like his five propositions:

1) that America’s “pursuit of happiness” had degenerated into a self-consumed, self-interested pursuit of materialism with serious consequences for the health and stability of the U.S. —especially since that nation has grown ever more litigious and misused its legal system and its completely legalistic view of ‘rights’ as the only means to solve social and personal problems which, in turn, has led to the tyranny of the individual over the general population.

2) that journalistic standards in the U.S. have become morally bankrupt because media reporting trivializes important events and people, shamelessly invades privacy, refuses to acknowledge errors in judgment, and has built up a comfortable collusion to prevent new views and hard facts from reaching the public.

3) that intellectuals in the West continue to be enamoured with socialism, despite citizens of such regimes repudiating its utopian illusions and despite its persistent spiritual threat which, regardless of its type or shade, always leads to the total destruction of the human spirit and to a levelling of mankind into death.

4) that Americans’ treasured ideas of freedom have become corrupt because there is no longer a belief in the existence of evil, leaving the nation defenseless against real evils that would destroy it, including pornography and a myriad of other social crimes such as abortion.

5) that the fundamental reason for mankind’s current woes and the West’s current weakness is the Enlightenment philosophy that claims man is independent from God and accountable only to himself, leaving nations spiritually depleted and morally anemic.

Taken together, these propositions add up to a major crisis for the human race, Solzhenitsyn concluded. So what did he propose the West should do to avoid catastrophe? We must cease deceiving ourselves that evil doesn’t exist, he said. “The dividing line separating it and goodness runs through every human heart. Therefore, we must stir up courage and resist evil wherever we find it, even if it means fighting it to the death. And finally, we must acknowledge God’s sovereignty over His creation, including mankind. No one on earth has any other way left but—upward.”

Forty years later

Forty years have now passed since the Soviet dissident gave his address that predicted the deepening decay of the modern world. Solzhenitsyn foresaw the collapse of faith in the West, our addiction to technology, popular culture’s hegemony over deeper forms of learning, political correctness, collegiate censorship, fake news, even Donald Trump. Indeed, to commemorate today the 40th anniversary of A World Split Apart by reading it, his words are not just relevant, but astounding.

As for Solzhenitsyn himself, he eventually returned to his homeland in 1990. And soon after, the Soviet Union as the world had long known it collapsed, but not before all the ‘isms’ it spawned had taken root all over the world, so as to infect and subvert it away from truth, justice and God.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn died in August 2008, four months short of his 90th birthday and mere weeks before the September 18 financial collapse of that year, confirming again the prophet’s diagnosis of America’s gradual disintegration.

Today, The Socialist Worker still doesn’t want us to celebrate him. Nor does it want any of us to be reminded of what he said.

“The Western world has lost its civic courage, both as a whole and separately, in each country, each government, each political party, and, of course, in the United Nations,” Solzhenitsyn told his audience at Harvard. “This was most obvious in the attitude of many Westerners toward Soviet aggression — particularly among the ruling and intellectual elites, causing an impression of loss of courage by the entire society. Political and intellectual functionaries exhibit . . . depression, passivity, and perplexity in their actions, and even more so in their self-serving rationales as to how realistic, reasonable, and intellectually and even morally justified it is to base state policies on weakness and cowardice.” Thereby leaving their nations wide open to all manner of threatening forces, including international terrorism, which they only pretend to fight.

Meanwhile, the struggle between good and evil continues unabated. And Lenin and Solzhenitsyn continue to stare cold-eyed at each other across the corpse-filled gorge of the 20th century.