We should pause and reflect – and pray, a verb which you will not often hear on the CBC – as we commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the end of what was called at the time the ‘War to End All Wars’, the ‘Great War’. It was only after the even greater conflict two decades later – excusing the ambiguity of calling wars ‘great’ – that the 1914-1918 conflict earned its title of the ‘First’ World War.

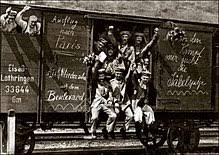

We are in many ways still fighting that war, for the Armistice, signed at 11 a.m. on November 11th in 1918 in that railway carriage forty or so miles north of Paris in the forest of Compiegne, sowed the seeds not only of the Second ‘World War’, but just about every other conflict across the globe. The Treaty of Versailles in June of 1919 – under David Lloyd George, Georges Clemenceau and Vittorio Orlando, and American President Woodrow Wilson – rather hubristically re-wrote the global map and was, to put things mildly, controversial, even, many now say, fundamentally imprudent and impossible, as that strange hybrid that was ‘Yugoslavia’, as well as the mess made of the Middle East, make clear. Germany was vengefully humiliated – something Wilson opposed and so went on to make America’s own peace – but the crushing of the proud nation laid the ground for the rise of someone like Hitler, himself a wounded combatant in the war, feeding upon and flaming into fire long-nursed resentment.

But we do celebrate the initially peaceful end of what many now view as an irrational war that savagely took millions of lives, and grievously wounded and maimed millions of others, a war that began almost accidentally and dragged on interminably, whose fruits were by and large disastrous. Although the Church has a doctrine on just war – with certain requirements spelled out by Saints Augustine, Thomas and others – in the concrete, even the ‘best’ of wars, which this was not, always contain elements of severe and grave injustice. Throwing millions of the young men of Europe into the gaping maw of machine gun fire and artillery shelling, day after day, week after week, year after year, to move the front line a few yards back and forth across muddy, bombed-out fields is a type of large-scale type moral lunacy, impelled by what we might assume was a strange pride and blindness. Ponder this grim statistic from Mark Steyn:

The belligerents had agreed the terms of the peace at 5am that November morning, and the news was relayed to the commanders in the field shortly thereafter that hostilities would cease at eleven o’clock. And then they all went back to firing at each other for a final six hours. On that last day, British imperial forces lost some 2,400 men, the French 1,170, the Germans 4,120, the Americans about 3,000. The dead in those last hours of the Great War outnumbered the toll of D Day twenty-six years later, the difference being that those who died in 1944 were fighting to win a war whose outcome they did not know. On November 11th 1918 over eleven thousand men fell in a conflict whose victors and vanquished had already been settled and agreed.

Pope Benedict XV – who condemned the war as the ‘suicide of Europe – proposed a peace treaty during Christmastide of 1914, a few months after the conflict began, but no one listened, both sides rejecting his initiatives. Rather, the unjust terms of ‘unconditional surrender’ were called for, prompting Germany, and everyone else, to fight to the bitter, bitter end.

The monuments say that the soldiers died for ‘freedom’, a concept of which most of our vaunted and benighted leaders know little. It’s a bit of a stretch to think that millions died so that the limits of our ‘freedom’ be dictated by socialists such as Trudeau and Macron, with sexual hedonism and abortion-on-demand. Macron used his own speech to condemn the bogey-man of ‘nationalism’ as the cause of war, and now wants a ‘European army’ to defend against American and Russian aggression. I don’t think this was what those soldiers died for.

Yet, in the midst of our current insanity, we pause to honour and remember the dead, those who gave everything, eking out their final moments in the midst of chaos and bloodshed, damp and dark trenches and artillery shelling, in what they may well have thought, at least at times, was a grand and good cause.

But we must do so without the shallow sentimentalism that seems to cover so much of our ‘remembrance’. For what does it mean to remember, and what should we remember? Are our recent conflicts and skirmishes ‘just’, and how do we as a nation justify our military actions? The bumper sticker that proclaims ‘If you don’t stand behind our troops, feel free to stand in front of them’ signifies such ‘sentimentalism’ – rather arrogantly and imprecisely expressed, I might add, for surely such signifiers do not mean one should face a hail of bullets for simply questioning the prudence of a given military endeavour. Was, to use an example that will come up below, the mission in Afghanistan, begun with whatever good intentions, in the end a debacle – albeit a far lesser one that the World War – but still overall a massive misuse of time, effort, money and, most of all, lives, which could have been foreseen from the get-go?

One should at least be permitted to ask such questions without demeaning the bravery and sacrifice of individual soldiers, nor the overall value of the military itself, and simple sloganeering signifies some absence, even in this case prohibition, of the serious and sober thought we should all have as free citizens on what a ‘just war’ means. Are we bound to support every overseas action of our ideological governments, past and present, especially unhinged as they now are even from natural prudence and wisdom?

And on a spiritual plane, how many, I wonder, of those standing out there wearing the ubiquitous poppies actually pray for the deceased? Or do they believe the fallen soldiers to be gone forever, just, well, memories? Do they value what they valued, and do they still fight for which they fought? Whose side are they on, if sides at some level we must choose as we journey towards our own judgement and eternity?

And what is one to say of this years ‘silver cross’ mother, whose son tragically committed suicide after returning from the Afghanistan mission in 2003? Whatever this sad, depressed young man’s culpability, taking his life as he was about to return home on Mother’s Day, we might ask what exactly we are commemorating in this, and what does this say about the sacrifice of every other soldier? Are we implying that such a death is somehow the same as all those who gave their lives, or more properly had them taken away from them, by dying in battle?

Whatever our answers, and as we continue, as is said, to fight for some nebulous ideal of ‘freedom’, we should remember most firmly that the only freedom worth dying for is the freedom in the truth that Christ offers. Everything else, as recent history has evinced, is just a subtle form of slavery.

Requiescant in pace, defensores pacis et libertatis.